Thirty years after the death of Sex Pistols front man Sid Vicious, a new documentary, Who Killed Nancy?, argues that Sid was not responsible for death of his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen. Legendary Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren says the idea was bollocks in the first place.

Sid Vicious was born John Simon Ritchie in 1957, and grew up as John Beverly. When he lived with his friend, John Lydon, they couldn’t both go by “John” so he took on their pet hamster’s name, “Sid” when the punk scene exploded and the name just stuck.

Early on, I met Sid when I was desperately searching for a singer to front the new band I had named “The Sex Pistols.” My erstwhile girlfriend tipped me off about someone named John. I looked out for him, but as fate would have it, I met the wrong John: John Lydon, John Simon Ritchie’s friend, as it so happened, who had heard about the audition and immediately jumped the queue before Ritchie.

“Who cares about love?” Sid once said to me. “Love is for people preparing to die.”

John Simon Ritchie arrived too late, but opportunity knocked when the bass player's mother threw a fit and Glenn Matlock promptly left the group. I used Sid to replace him. It was then we started calling him “Sid Vicious.” John Lydon had already been christened “Johnny Rotten.”

Sid soon took on the mantle of the most controversial icon of his generation. I often wondered if he stood up to James Dean in terms of style and sexual attitude. He wished to be called “the Eddie Cochran of Punk Rock.” Sid was everything everyone else was not, both good and bad. He impressed us all and embarrassed us all. He never saw a red light, only green. He should have been buried next to Karl Marx in London’s Highgate Cemetery. I was determined for this to happen, but his mother thwarted my efforts and had him burnt to cinders in the US instead.

So many people have cursed me, accused me, of murdering Sid, including John Lydon. That’s not true. Sid’s mother did. Some felt that because I was the manager, the “responsible adult,” I could have prevented Sid’s death. But try managing a junkie—especially if you’ve never been one yourself. I guess that’s show business and the media. The questions never stop, even now, 30 years since his death. “How Vicious was he?” “What went wrong?” Did he kill Nancy? To the last question, I can say, definitely not. But more on that later.

Sid Vicious began the age of participation in which everyone could be the artist. Sid proved that you don’t have to play well to be the star. You can play badly, or not even at all. I endorsed that attitude. If you can’t write songs, no problem—simply steal one and change it to your taste. What matters is this: Being fearless of failure arms you to break the rules. In doing so, you may change the culture and just possibly, for a moment, change life itself.

Punk Rock created a new kind of teenage angst. Sid embodied this in his sound and stance. To watch him was to watch a naïve, vulnerable, sad, beautiful and ugly teenager being loved for doing something different. He lowered the bar of entry and allowed everyone into the creative process. The line between the audience and band was blurred. Sid was once the Pistols fan who invented the Pogo (a dance involving jumping in once place and thrashing about). It created chaos, threw the fan at the feet of the band and suddenly, the fan was the center of attention and the star.

And then, Sid the Fan became the star. At a sound check on the Dutch tour, Johnny Rotten, as usual, refused to work with the rest of the band. This time, Sid gladly replaced Rotten on vocals, singing every song word perfect and in tune. I’ll never forget John’s face drowning in his beer, Steve Jones’s bemused expression, and Sid so natural. He had out-punked them before John could even blow his nose.

Sid spelled trouble wherever he went—a wicked, sexy kind of trouble you can’t resist. He was the ultimate DIY Punk Idol: someone easy to assemble and therefore become. Sid didn’t just wear the clothes; he acted them. He single-handedly reinvented the classic Havana tuxedo into an outlaw costume by styling it with a pair of black drainpipe jeans and what would become the ubiquitous Punk garter that he wore so sweetly around his left thigh. His vocal performance on “My Way,” with its venomous tirade against his former friend, Johnny Rotten, outpaced—and many say, outsang—Sinatra’s. Martin Scorsese seemed to think so, as he included it in his film, “Goodfellas.” Paul Anka, the original lyricist, has been quoted many times saying that Sid’s is his favorite version.

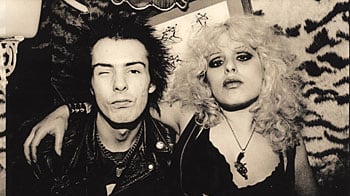

Sid made sex purposely corny and mundane—making it easy to overcome adolescent inhibitions. Everyone wanted to sleep with Sid (except for Marianne Faithfull, who was being cast by Russ Meyer—“King of the Nudies”—to play his mother in Who Killed Bambi?, the aborted Sex Pistols movie. She insisted he take a bath first.) Provocative and dangerously sexy, he stretched the limits. So typically young and foolish, his vanity was sublime and wonderfully cheeky. Making love seemed a too-distant subject. “Who cares about love?” Sid once said to me. “Love is for people preparing to die.” But he was willing prey for Nancy—Nancy, who taught Sid all about sex and drugs and the lifestyle of a New York rocker.

His defiance toward accepted values made him a serious threat in the band, and the music industry made no attempt to hide their feelings. Throughout his short career, they conspired against him with whomever would help, including Johnny Rotten. They said he was capable of anything.

But to kill Nancy? I was stunned when I first heard this and I still can’t believe it. Sid was capable of a wide range of self-destructive acts, but I didn’t think that he could kill someone, especially his girlfriend, unless it was a botched double suicide. No! I don’t believe Sid killed Nancy. She was his first and only love of his life. As everyone knows, you may argue with your first (he lost his virginity to Nancy), sometimes might want to beat their brains in, leave them, move on, and be with others—but you never get over them. No. Sid was the sucker. The stupid, clumsy fool that night at the Chelsea Hotel. He passed out on the bed, having taken fistfuls of Tuinal. All around him, drug dealers, friends of Nancy came and went from Room 100. Money was stolen and Sid’s knife (similar to that of 007’s) was taken from the wall where it was hung and seemingly used by someone defending themselves in a struggle with Nancy. Nancy was no pushover. I tried having her kidnapped in London and put on a plane back to New York. Probably, she caught this person stealing money from the bedroom drawer.

I was positive about Sid’s innocence and acquittal. But Sid’s trial was going to cost a fortune, and with the Sex Pistols account drained, I thought he could sing for his supper at the Sands in Las Vegas and pay the bills. Sid already had several hits under his belt—covers of Eddie Cochran’s “C’mon Everybody” and “Something Else” as well as “My Way.” During the preparations for Sid’s trial, my conversations with various promoters had me contemplating Sid performing in Las Vegas. After all, Sid was the only Punk candidate who could fill Elvis’s shoes.

Sid’s mother, Anne, was kind enough and helped him wherever she could. A small-time drug dealer, she smuggled heroin in her vagina to Sid at Riker’s Island, a detention center in New York where he was awaiting trial for the murder of Nancy. A dutiful mother, she aided him in his last breath, killing him, and killing herself years later.

Sid Vicious’s face has peered out of more T-shirts, posters, documentaries than any other rock star of his era. His uncanny ability to imitate art and yet at the same time naturally claim it as his own is a Warholian dream. At my store, Sex, on the King’s Road in Chelsea, Andy Warhol pleaded desperately for a T-shirt with Sid’s name printed on it, “Malcolm, just do it for me, just one!” Later, Andy would paint Sid’s portrait for the cover of an art magazine. Sid was the Sex Pistols’s problem—but alas, the rest of the band could never agree that he might also be their Savior.

Malcolm McLaren began his career in fashion and entertainment in the early 1970s when he opened a store in London with Vivienne Westwood, kickstarting punk fashion. He then founded and managed the Sex Pistols, and worked with artists like Boy George, Adam Ant, and Bow Wow Wow. In 2006, Fast Food Nation, a film which McLaren conceived and co-produced, débuted at the Cannes Film Festival. Presently, McLaren is developing a stage musical about fashion for Broadway.