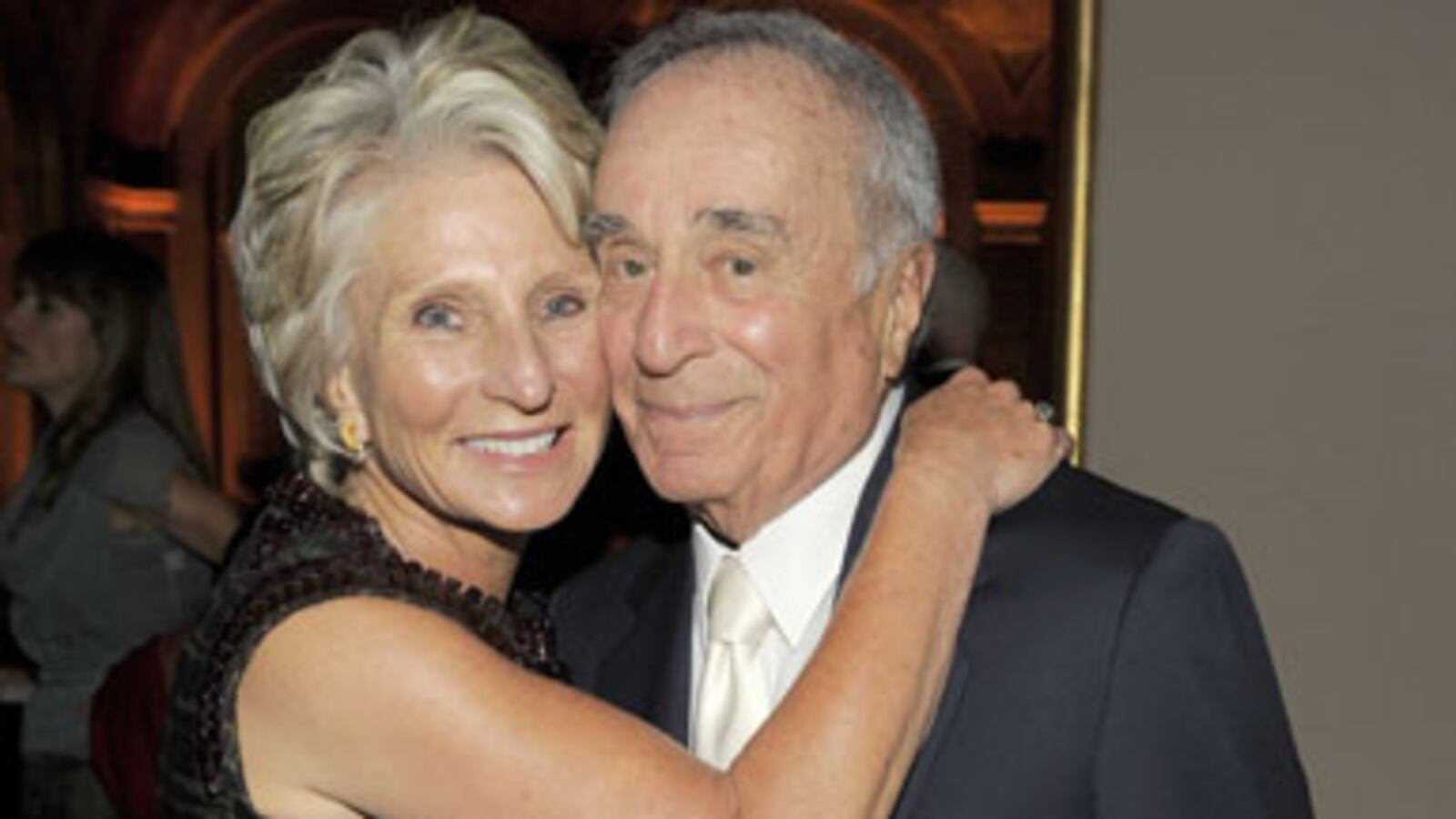

The late Newsweek/Daily Beast owner’s cultural interests, passion for life, and commitment to social justice were lauded at a memorial where speakers included President Clinton, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, and Lynn Harman, who said of her father: “He was magic.” Eleanor Clift reports.

It was billed as a memorial celebration, and the afternoon that unfolded at the concert hall in Washington that bears his name conveyed Sidney Harman’s range of cultural interests, his passion for life, and his commitment to social justice. The businessman and philanthropist died last month at 92, and his daughter, Lynn Harman, said that five days after a diagnosis of acute leukemia he began planning this memorial “with every intention of attending,” she said, as though he didn’t want anyone to say, poor Sidney, he missed the party.

And a grand party it was, with a former president, a Supreme Court justice, and countless admirers paying tribute, interspersed with readings from Shakespeare and performances by the Washington Ballet, Yo-Yo Ma, and a step-dance team of hip young African-American kids that drew sustained applause.

“He was magic,” Lynn Harman said of her father, recalling how he invented storybook characters and would playfully pull coins from the ears of children around the world. “He spoke child,” she said. But he could be tough. When the civil-rights movement got under way in the 1960s and he went off to teach in segregated schools in Prince William County, Virginia, Lynn was grounded for six months when someone called the house, identified himself as Martin Luther King, Jr., and she blew him off with, “Right, and I’m Joan Baez.” It was of course, Dr. King.

When Lynn had her first child and only fathers were allowed in the recovery room, Sidney insisted, “I am the father.”

“It was impossible to argue with his logic or authority,” she said. The night before he died, a nurse struggling to draw blood, said, “Dr. Harman, you should have veins like your daughter.” “Then take the blood from her,” he said.

President Clinton, looking slender and sober in a black suit, promised to stay within his allotted five minutes, and he did, recalling a visit to Harman’s stereo company in Northridge, California, and how impressed he was by how the workers were treated. When layoffs were necessary, Harman gave them a chance to set up a factory within the factory using surplus wood not used for cabinets to make clocks or desks they could sell and keep the profits. “That tells you something about his values and his creativity,” Clinton said. “He was a young man at 92 because he never forgot what mattered.”

“He was a young man at 92 because he never forgot what mattered.”—President Clinton

President Clinton recalls visit to Harman’s stereo company

Harman loved Shakespeare and could recite huge chunks of plays from memory. Justice Stephen Breyer said he brought these lines to life, and that he believed these “literary gems shed light on contemporary problems.” Harman lived through the Great Depression and he heard FDR speak, “But he did not live in the past,” said Breyer, instead “using the past to inform the future.”

Harman would say what kept him young was his humor and his curiosity, said journalist Andrea Mitchell. “There was no one better at making a toast and he never needed a note—or a teleprompter,” she said. “He was always smarter, funnier, and better company than anyone else in the room.”

On cue, as if to prove the point, a commencement speech Harman delivered on the occasion of his 70th reunion at Baruch College appeared on a big screen. Acknowledging that the graduates were curious to see what a 92-year-old man looks like, he preened for the crowd and said, “I am my own invention. How you go about doing that is who you are.”

Someone who reaches the age of 92 is often asked what is his or her secret. Harman would say that he got up every morning determined to change the world, and also to have a good time. “Engaging with life and wrapping your arms around it makes you still young at 90,” he said when he reached that milestone. Asked what he would like on his tombstone, he said, “Still curious.”

Much of the celebration harkened back to Harman’s early years, but his acquisition of Newsweek last summer became the capstone to his remarkable life. When he greeted Newsweek staffers last August in New York, he said he hoped that day would be the last when he would be referred to as the magazine’s owner, a word he said “makes me cringe.” On NPR’s Diane Rehm show a week before he died, he said he didn’t come to Newsweek as a business proposition, that he came to it “with the conviction I had serious contributions to make and they were not in the bookkeeping department.” He described the magazine he envisioned as “a balance between the serious and the seductive.”

Washington Post Company Chairman Don Graham drew laughs when he told the story of “how I made a dollar off Sidney.” He recalled having breakfast with Harman the morning the Post announced it was selling Newsweek. “The announcement caught Sidney’s eye,” said Graham, who didn’t take him seriously. “Always a mistake with Sidney,” he added. Harman bought the magazine for a dollar and some $40 million in debt.

Then he set about wooing the editor he wanted, Tina Brown, who was among the final speakers to take the stage. “My first serious encounter with Sidney began like the opening reel of a romantic comedy,” she said, describing a clandestine meeting in the Hamptons that had been arranged with such secrecy that she forgot it. “I stood him up,” she said.

He called. “I’m sitting at Barrister’s [restaurant in Southampton] and you are not. Perhaps you can help me solve this mystery.” Finding humor in the occasion as opposed to being irritated was Harman’s gift, said Brown, who wondered why this jaunty, vigorous man of 63 or so was going around pretending to be 91. “He referred to himself as ‘the Kid,’” she recalled, adding that the new logo of the merged Newsweek with the Daily Beast was his design. “The romance that began last summer was all too brief,” she said. For a man who lived 92 years to leave everyone wanting more—there is no better tribute.

Eleanor Clift is a contributing editor for Newsweek. Follow her on Twitter.