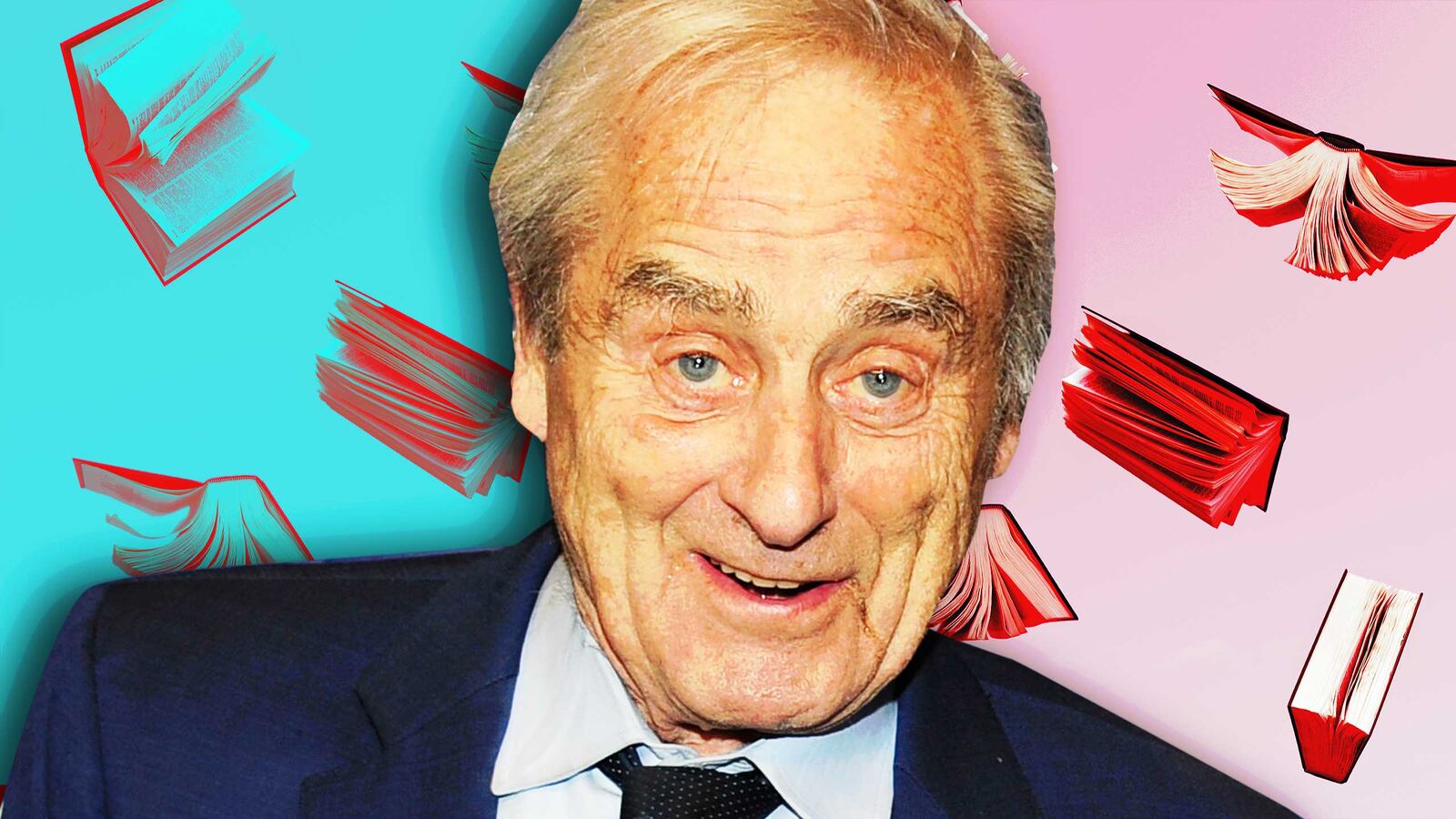

Sir Harold Evans has had more lives than the luckiest cat.

The English-born former editor of The Times of London and The Sunday Times has also served as editor in chief at Random House, founded and edited Conde Nast Traveler, and worked for US News and World Report, The Atlantic Monthly, the New York Daily News, The Week, the BBC, and Reuters. A prolific author, he has published numerous books whose subjects range from the American Century to engineering and technology and autobiography. He is also a competition-level ping pong player.

And now, at the age of 88, he has shapeshifted once again with a new book, Do I Make Myself Clear? Why Writing Well Matters, a writing manual so smart and incisive that it could surely benefit anyone—journalist, student, business executive, legislator—who has ever tried to craft an English sentence and fallen short. Or, as he puts it, “First I was a poacher. Now I’ve become a gamekeeper.”

“When I left newspapers, I was still engaged in words, and I got more and more frustrated by two aspects of the reading I was doing: when a story wasn’t properly investigated and in seeing how people were being misled by language, particularly by the politicians,” he explained over tea and scones one recent afternoon at the New York City townhouse he shares with his wife, Tina Brown, founder and first editor of this website and the former editor of The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Tatler.

“Take, for instance, the talk of ‘death panels’ used to scare people away from the Affordable Care Act—I call it the Affordable Scare Act. That made me angry because they were deliberately misusing language. A lot of language misuse is because people don’t understand the difference between, say, decimate and kill. But a lot of it is deliberate, written up in insurance policies, written up by politicians, and so on.

“I wrote the book because I thought I had to speak up for clarity.”

As if he’s suddenly aware of the fierceness that’s crept into his voice, he laughs. “I mean, I’m a bloody menace. When I go in a café in the morning for breakfast and I’m reading the paper, I’m editing. I can’t help it. I can’t stop. I still go through the paper and mark it up as I read. It’s a compulsion actually.”

The book inspired by that compulsion is unpretentious and practical-minded. Casting a cold eye on an endless stream of bad paragraphs and sentences, Evans shows you how to squeeze out the bloat, eradicate confusion, and embrace specifics that dispel the fog of generalities blanketing so many government regulations, corporate reports, news stories, or even emails between friends. After decrying the vague words that leach the life from prose, words like amenities, activities, facilities, indication, and eventuality, he sums up: “Sentences should be full of bricks, beds, houses, cars, cows, men, and women.”

His black slacks held up by suspenders over a slightly ink-stained pink shirt, the octogenarian Evans hums with the energy of a man half his age. Whether catapulting from his chair to answer the phone or directing a delivery man to the kitchen, he’s up and down like a frog on a hot stove, and all the while fielding questions, including a few that hadn’t even been asked yet.

“I’m not talking about grammar,” he says at one point while leaning over to pour more tea (milk, no sugar, and he skips the scones). “Don’t be frightened of grammar. Don’t be afraid to write. One of the points I want to emphasize is, I don’t care if you get that and which mixed up or who and whom. I’m much more concerned with, is the meaning clear? I heard someone on TV say, ‘They advocated against it.’ You can’t advocate against something. These things make me crazy.”

Here and elsewhere, you have the sense of a man so in love with words that his first instinct is to protect them. “Everyone ought to have a word they hate to see misused,” he says, “so they can become more attentive to other words being badly handled.”

Like George Orwell, Evans understands in his bones that words are not just pretty things, that in the wrong hands they can mislead, betray, and even cause great harm. Beginning on page one and running right through to the end of the book is an iron spine of fair play and honesty. “This book on clear writing is as concerned with how words confuse and mislead, with or without malice aforethought, as it is with literary expression,” he writes in the introduction, and then circles back on the last page of the book to drive home the point once more: “The fog that envelops English is not just a question of good taste, style, and esthetics. It is a moral issue.”

If that makes Evans sound like a scold, you should know that while he can be stern, he is also very funny and as entertaining as he is instructive. Consider the following observations from his book:

“Murphy’s Law—anything that can go wrong, will go wrong—is vindicated every day. I propose the Evans Corollary: anything that goes wrong will always be wordier than anything that goes right.”

“Sentences in the active voice should be favored by writers and editors—or, rather, writers and editors should favor sentences in the active voice.”

“I am not so cynical as to believe government agencies are in conspiracy against the common man. I just wish they spoke the same language as the rest of us.”

And decrying the prose of President Warren G. Harding, he writes that Harding’s “writing had the thud of jelly spooned onto a paper plate.”

Near the end of the interview, he ponders the question of who it was who first used language not to clarify but to obfuscate—was it lawyers?

“They’ve got a lot to answer for,” he says with a grin. “In Shakespeare, they say, ‘The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.’ Lawyers are marvelous at obfuscation and less so at clarity because both sides have an idea of where there may be loopholes and they want to leave the opportunity to create one. Maybe there’ll be some nirvana where the last two lawyers kill each other over the meaning of a word.”

[Note to reader: If Harold Evans had written or edited this story, it would be at least 50 words shorter.]