A digital lifespan of 10 seconds. No record of your goofy selfie.

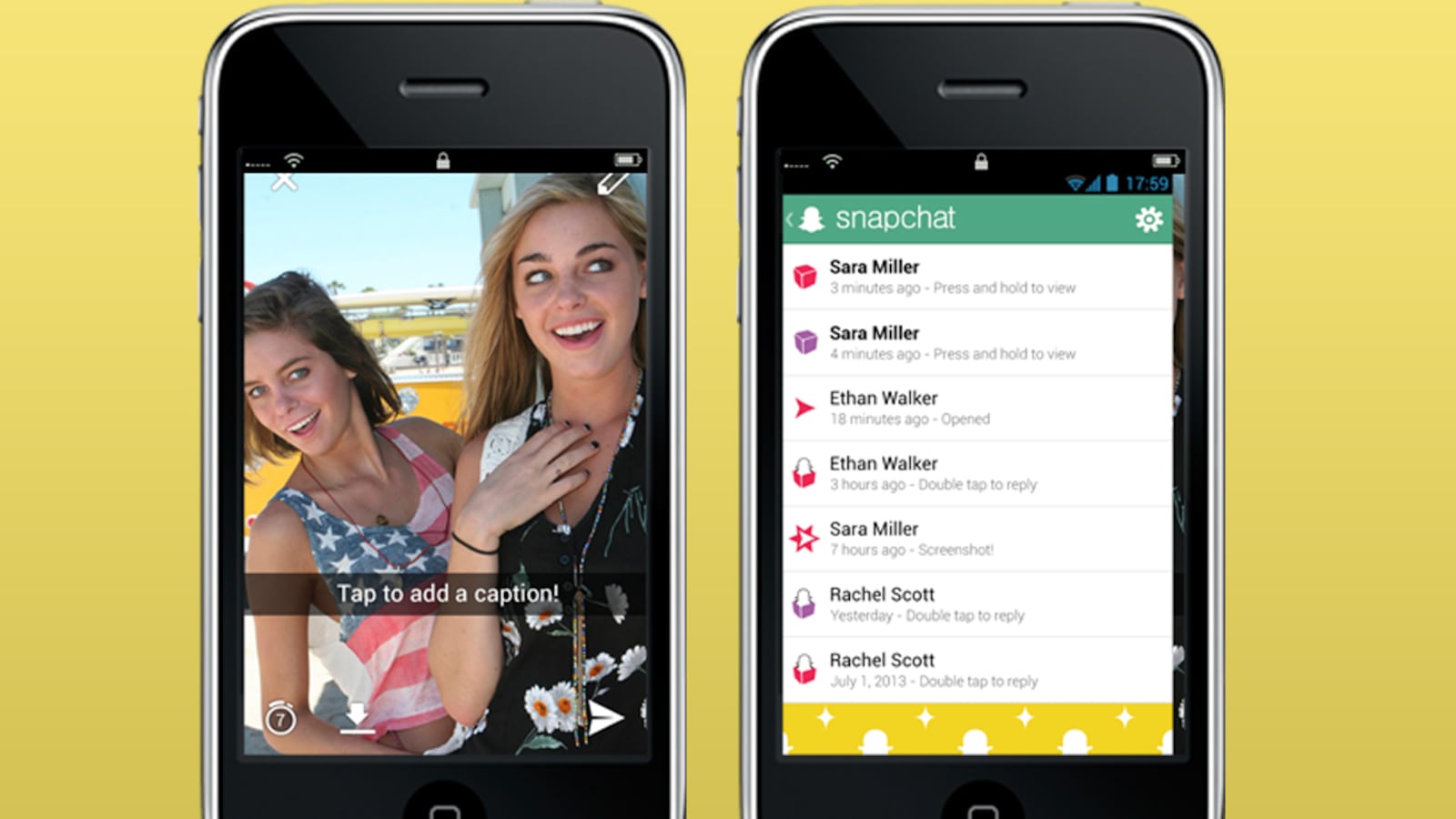

This is the promise of Snapchat, the mobile app that theoretically allows users to send whatever silly or ugly or dirty picture they want, to whomever they want, and never have it come back to haunt them, to leave no digital trace. It is a false promise, as anyone with the technical chops to run a screen capture knows, but that doesn’t really seem to matter.

Snapchat users are now sending 350 million images to one another every day, up from 200 million in June and 20 million a year ago. Be it safe, be it foolhardy, Snapchat appears to be on fire.

Why? For some of the company’s deep and philosophical execs, the app is so popular because it represents this intense desire people have to be in the here and now. In a lengthy blog post on the company’s website, staff researcher Nathan Jurgenson posits that it’s a false assumption that everything we say and do on social media is destined to remain embedded in digital archives until The End of Time.

“What would the various social-media sites look like if ephemerality was the default and permanence, at most, an option?” Jurgenson wrote, and after more discussion about how the archiving of everything diminishes the actual value or significance of each thing, admitted this: “Am I fetishizing the ephemeral, the present, the current moment? To a degree, yes.”

So there’s that, the company line. Om shanti om. But it takes about 30 seconds of Twitter searching to look at Snapchat in a whole new red light: the autocomplete, for example, is: “Snapchat me naughty pics.” Top Snapchatters, apart from the official @Snapchat handle, include “Slutty Snapchat” and “Nude Snapchat.”

It’s for sexting, obviously. Or at least, it’s often for sexting. Anthony Weiner might be picking out chairs for the mayor’s office today if the app had been around. Lest you think this is just about some mostly innocent fun between two people already in an intimate relationship, it isn’t, said Adam McLane, co-author of A Parent’s Guide to Understanding Social Media. There are adolescent boys all over America soliciting naughty pics from adolescent girls, he says. And there are adolescent girls broadcasting their Snapchat handles on their Twitter pages, tempting anyone on the Internet to “add” them, to get the party started.

Because there’s no searchable database of these disappearing pictures, though, there’s no way to truly ascertain the ratio of naughty versus goofy. Snapchat didn’t reply to requests for comment, but co-founder Evan Spiegel has said that the vast majority of the pictures exchanged are PG, and there are many others who say they only use Snapchat because it lets them send ugly pictures, not sexy ones. (Because that’s fun, to make a stupid face and pass it around without worrying about it landing permanently on a Facebook page.)

All of which is fine and good, says Larry Magid, co-director of ConnectSafely.org, a resource for kids and parents to navigate the world of social media, as long as Snapchat users remember that anything you send into the online ether can be stored. Snapchat does its best to discourage that: if the recipient of one of your pictures takes a screen shot of it, you’re notified. And if you set the duration for one second, it’s pretty hard to imagine how anyone could fire off a screen shot in enough time.

“Unless somebody goes out of their way to capture your image, chances are it will disappear,” Magid told The Daily Beast.

Those aren’t foolproof protections, notes Magid, who recently authored a “Parent’s Guide to Snapchat.” If you’re expecting a dirty “Snap” and you’re determined to keep it, you could always use a video recorder and record the image coming through on a phone. But that’s certainly more legwork than would be involved in storing the image from a dirty text, of course. And it means that most of the time, most of the pictures people send really will disappear forever.

In this way, the rise of Snapchat demonstrates an odd kind of social-networking puberty. Yes, it’s used to send immature content, but it’s mature that young people (who make up the bulk of Snapchat’s user base) are using it because they think it protects their online identities.

“That people do it in this volume really points to the fact that they really want a solution to this kind of interaction,” said Anthony Rotolo, a professor at Syracuse University who studies social media. “People are turning to Snapchat to be themselves. To share these goofy moments they don’t want to end up somewhere else.”

Five years ago, teenagers were far more stupid and careless about what they tweeted and what they photographed and where they sent it. Now, they realize college admissions staffers are peering into their Facebook photos. Flawed as the actual methodology may be, it’s encouraging that young people recognize the need for it, Magid said. “Teens have gotten the message that there are consequences to what you post,” he said.

The irony of all this is that in some ways, texting naughty pictures might actually be safer than Snapchatting them, said McLane. Company officials say they’re not storing these images, but there have been cases of Snapchatted images being used as evidence in court cases. Last week, for example, police in Fargo, N.D., executed a search warrant on a 13-year-old girl’s phone after a fight between the girl’s brother and another boy who alleged sent her Snaps of his genitals.

Text messages “are at least protected by the FCC,” McLane said. “But with Snapchat, if they decide to publish your photos at some point, you’d have no legal recourse.”

It’s hard to imagine, then, any sign of Snapchat slowing down. But the next question is the inevitable one, no matter how booming the startup: can it make money? Adrian Salamunovic is skeptical. Because Snapchat’s interactions are one-to-one and not broadcast (yet), it’s tough for companies to find ways to piggyback on the messages and make a quick buck or two via advertising or sponsored Snaps. There’s no “ecosystem,” said Salamunovic, the co-founder of Canvas Pop and a longtime Web consultant who has been tracking the development of social-media phenomena like Snapchat. And that poses a clear threat to the app’s ability to monetize.

“I can’t see a single corporate use for it,” Salamunovic said. “I don’t know of any companies taking advantage of Snapchat in any way. It’s too one-on-one. I don’t think it’s fully scalable.”

That said, when your company’s user base is growing as explosively as Snapchat is, it’s a reasonable bet that someone is going to rake in a truckload of dough at some point.

“They’re going to monetize it by selling it, at least the founders will,” Salamunovic said. “I can see a big acquisition coming in from Yahoo or AOL; another billion-dollar deal, potentially.”

What then? Depends on how the company innovates (or fails to), and whether a competitor comes along with the newest way for people to entertain each other. Safely. Sort of.