The holy sinner.

To some, the term is a contradiction: Surely the sacred and the profane are opposed to one another, never to be brought together. But to some of the most God-intoxicated, it is part of being awake to the conundrum of the human condition, aware of the holy but horny as hell; aware that the pious are often the most hypocritical. And aware that all of us are in the gutter, as Oscar Wilde said, but some of us are looking at the stars.

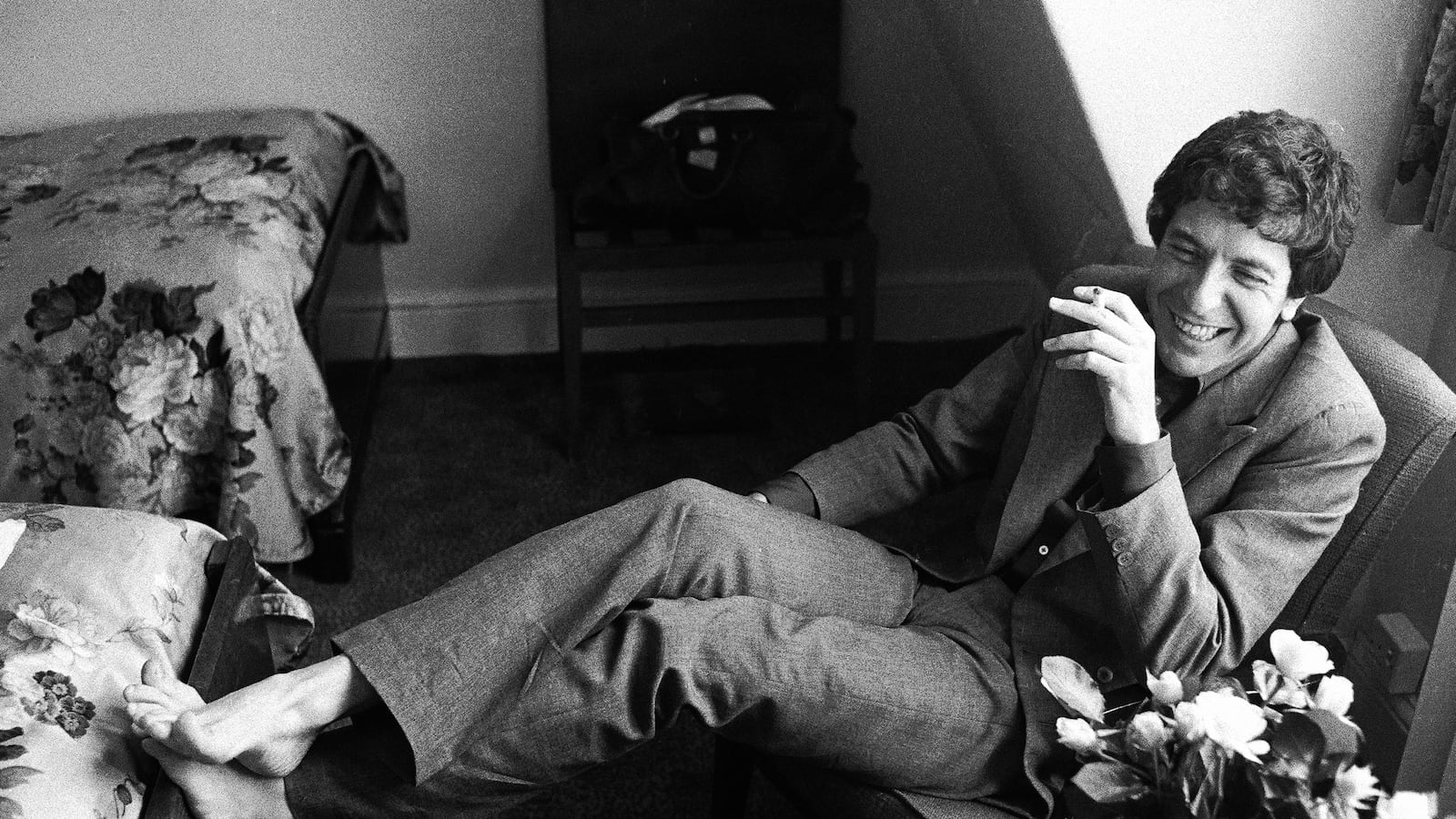

The world has lost a great holy sinner, the poet/singer/songwriter Leonard Cohen, who, it was announced Thursday, passed on to his eternal reward at age 82 just three weeks after releasing a brilliant final album, not unlike David Bowie earlier this year.

Like other outlaw saints—Johnny Cash first and foremost—Cohen had several careers in the course of his life. He was a hipster poet in the early 1960s (the film Ladies and Gentlemen, Leonard Cohen is a hard-to-find gem) before setting some pieces to music, mostly performed by others, in 1967. From then until the mid-’70s, he was the intellectual’s Bob Dylan, never achieving Dylan’s fame but outshining him in writing songs of personal desolation, erotic yearning, and biblical imagery.

Like Cash, and Dylan for that matter, Cohen also spent a fair amount of time washed up, only hitting his stride again with comeback albums in 1988 and 1992. And then he disappeared from the music business for a decade, residing for a time at a Zen monastery, publishing more poems, and, while absent, growing in his legendary status.

Finally, in his last decade, Cohen came back again, releasing some of his best-selling albums and finding a new audience for his work. In these last albums, and in a surprising world tour, undertaken at age 80 in part because of financial mismanagement, Cohen was both elder statesman and vital artist, reaching the largest crowds of his career

To younger readers, Cohen is probably best known as the author of “Hallelujah,” which has been covered many times (for better or for worse), most famously by Jeff Buckley, Rufus Wainwright, k.d. lang, John Legend, and Bon Jovi. It is purported to now be one of the most covered songs in popular-music history.

Like other iconic songs, though, it has also become a bit misunderstood. When the Buckley version of the song was played at Fenway Park in memory of the victims of the Boston Marathon terror attack, “Hallelujah” became a hymn, its minor chords providing a wistful tone appropriate to such a somber occasion.

Probably those in attendance didn’t hone in on lines like “Remember when I moved in you / The holy dove was moving too / And every breath we drew was Hallelujah.” Hell, I’ve played the song by many campfires and it’s not the part I emphasize either.

GALLERY: Leonard Cohen's Life in Photos

But it is the essence of Cohen’s art. In the song, King David pleases the Lord with his secret chord—but he is also the King David who sees Bathsheba “bathing on the roof” and, in the biblical story, arranged for her husband to be killed in battle. Cohen doesn’t spell out the biblical details, but retells the story with Bathsheba breaking David’s throne and, from his suffering, drawing out the Halleluyah. The true praise of God emerges from eroticism, from being rendered abject by a cruel lover.

Cohen’s muses, too, were often women with whom he was erotically entangled. He was, as one of his album titles alleged, a ladies’ man—writing songs of desire well into his seventies. “Bird on a Wire,” “Suzanne,” “So Long, Marianne”—these songs are not widely known, but they are dearly loved by those who know them.

Cohen’s was not a Catholic spirituality, pulled between opposing poles of God and sex. Rather, his was a secular, Jewish, Buddhist spirituality, which drew “halleluyah” from the open mouth of orgasm; which both saw the futility of human wanting and the beauty of embodied yearning. One of his last books was called The Book of Longing.

Yes, Cohen spent time living at a Buddhist monastery, but the Zen tradition of which he was a part is filled with its own iconoclasts—like Ikkyu, the 14th-century master of Japanese poetry, who scandalized his contemporaries by cavorting with prostitutes, getting drunk, and railing against the institutional hierarchy of Zen Buddhism—all as a fully enlightened Zen teacher. “Don’t hesitate to get laid—that’s wisdom,” he wrote in one short poem. “Sitting around chanting? What crap.”

Nor, of course, was Cohen’s Jewishness of the pious kind. It’s not that Cohen did or didn’t believe in God, the afterlife, and all the rest. On an intellectual level, of course he did not. But like the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber said, if we are speaking of God in the third person, I do not believe in God; but if we are speaking directly, in the second person—as You, then I do. That is to say, true religion isn’t prose, telling us things about the world, but poetry, expressing human longings and fears.

It’s inevitable that Cohen’s death will be understood by its coincidental timing with the ascendancy of Donald Trump, who represents the antithesis of everything Cohen’s brutal integrity stood for. It’s almost as if Cohen’s final song, “You Want It Darker,” has indeed come to pass:

If You are the dealer, I’m out of the game

If You are the healer, I’m broken and lame

If Thine is the glory, then mine must be the shame

You want it darker—we kill the flame.

Magnified, sanctified is your holy name

Vilified, crucified in the human frame

A million candles burning for the help that never came

You want it darker—Hineni, Hineni, I’m ready, my Lord

This is Cohen confronting his mortality—“Hineni” means “Here I am” and is used often in the Bible to denote standing before God. But now, thanks to coincidence, it’s also about how we human beings kill the flame of compassion, vilify God incarnate, and light candles in vain, hoping that some puppetmaster God will save us from ourselves. It’s as if God wants it this dark, wants to see just how dark it can get. This is what Cohen growls over the voice of a cantor, quoting the Jewish “kaddish” prayer (“magnified, sanctified”).

If there is any hope Cohen offers us in our darkening societal moment, it comes from an earlier song, “Anthem,” which speaks of “the widowhood of every government” and assures us that “The wars they will be fought again / The holy dove be caught again / bought and sold and bought again / the dove is never free.”

But don’t believe the obituaries that tell you that Cohen was just some master of the sad song. “Anthem” continues by quoting the Sufi poet Rumi: “Ring the bells that still can ring / Forget your perfect offering / There is a crack in everything / That’s where the light gets in.”

Yes, we are all of us, individually and collectively, deeply and irredeemably broken. No salvation here, no Christ, no rules to live by to assure our own redemption, no patriarchal leader to bring us to imagined greatness. It will get worse, darker, bleaker. The vulnerable will pay the worst price.

Yet precisely in the broken, frail frame that is the human condition—precisely in the vulnerability, failure, and loss—is where the light gets in. Smiling at strangers on the subway in the wake of this horrible loss. Admitting that we all have our inner Trump, our inner tyrant, our inner terrified boy or girl who wants to grab anything that provides a sense of security. And letting go, and failing, and letting go again. “Beautiful Losers,” to quote another Cohen title.

Losing Leonard Cohen is like losing my grandfather. He was 82, he was ready, he lived a beautiful, messed up life. But I feel I’ve lost someone who made my own world a little more secure. I feel a little more lonesome.

Once, a friend of mine who was performing with Cohen asked if he’d read any of my work—since I’d reviewed him several times in the past. He had, she told me later, and he passed along this greeting to me, one Buddhist Jewish sinner to another: Shalom, Dharma Brother. It’s truly one of the best things that’s ever happened to me.

So, Shalom, Dharma Brother. Godspeed. And I’ll give you the last word, of course, from your most famous song, which now they sing at baseball games, but which is a better epitaph than any I could write:

I did my best, it wasn't much

I couldn't feel, so I tried to touch

I've told the truth, I didn't come to fool you

And even though it went all wrong

I'll stand before the Lord of Song

With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah.

Hallelujah.