A Cold War spy. A ballet dancer. A disguised blackmarket trader. Perhaps, a sailor.

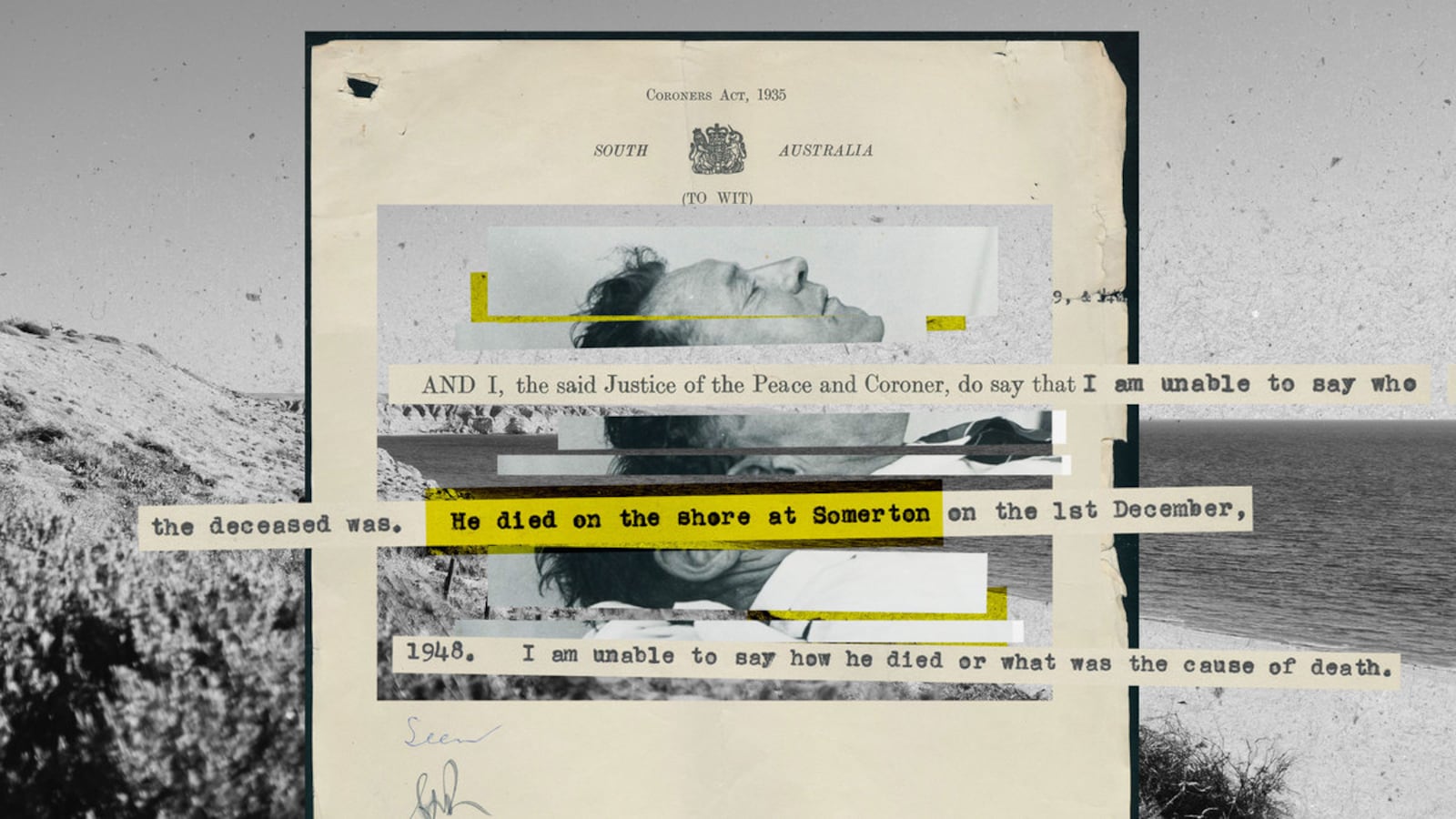

They’re just some of the theories about the type of work that might have brought an unknown man to Somerton Beach in the South Australian city of Adelaide where his body—dressed in a suit and tie—was found slumped against a seawall on Dec. 1, 1948.

It’s a case that has puzzled investigators and attracted amateur sleuths from around the world for decades and even saw the mystery man’s remains exhumed last year to undergo advanced DNA testing. But the identity of the so-called Somerton Man remains unclear more than 70 years on. No one knows who he was, what he was doing in the area, where he came from, or even how he died. But many intriguing clues were left behind.

The man had a partially-smoked cigarette resting on his collar with no apparent burn mark, his hair was immaculately styled and his double-breasted jacket was pressed. The tags on his clothing had been cut off. His pockets contained chewing gum, a box of matches, a pack of cigarettes, unused train and bus tickets, and an aluminum comb not sold in Australia.

The Somerton Man was found dressed in a suit and tie and slumped against a seawall.

Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/South Australia State RecordsIn January 1949, a suitcase was found at Adelaide Railway Station and linked to the man through a spool of thread that matched repair work in his pockets. It contained an odd assortment of items including clothes which also had their labels removed. But still, there was no identification, or anything to help connect the dots as to who the man was.

The clothes were all examined by experts, according to Tamam Shud: The Somerton Man Mystery by Kerry Greenwood. The police called in a tailor, Hugh Possa of Gawler Place, who explained that the careful construction of the coat, with feather-stitching done by machine, was definitely American, as only the U.S. garment industry used a feather-stitching machine, Greenwood wrote.

Several months later, pathology Professor John Burton Cleland found a tiny rolled-up piece of paper hidden deep in the fob pocket of the man’s trousers with the Farsi words “Tamam Shud”—which translates to “it’s finished” or “it is ended”—printed on it.

The torn paper was later traced back to a book of ancient Persian poetry, the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which had been left in the back seat of a car near where the body was found. Some believe this to be proof he was a spy or double agent that was executed. In the back of that book with the missing page there was an encrypted message which the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Scotland Yard code-crackers have both been unable to decode. It read:

“W [or possibly M] RGOABABDWTBIMPANETP

“MLIABO AIAIQC

“ITTMTSAMSTGAB"

Clues left in the man’s pockets at suitcase seemed to only further confuse investigators.

Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/South Australia State RecordsA phone number was also scribbled in pencil on the back page of the Somerton Man’s Rubaiyat. It belonged to a local nurse called Teresa Powell or Johnson who was interviewed by police and said she did not know who the unidentified man was before she died in 2007, according to Tamam Shud: The Somerton Man Mystery.

The Somerton Man was well-built, about 40 to 50 years old, 5 feet, 11 inches tall, with grey-blue eyes and gingery-brown hair that was greying at the sides, according to authorities. He had what the pathologist referred to as a “fine Britisher face”.

Mr Cleland also noted that: “Many people who find their way to the morgue have toenails which are dirty and unattended to. His were clean.”

There has been some speculation among internet sleuths that the Somerton Man may have been poisoned by a jilted lover. An autopsy found an enlarged spleen and a liver in poor condition but could not determine a cause of death, factors that led to speculation of poisoning; though no trace of any poison was found it also could not be ruled out. Examiners also found that the man had unusually strong calf muscles, a detail that fed the idea that he had ballet training and could have been a professional dancer. Other theories about him include that he was simply an American sailor who traveled to Adelaide to visit a child he had fathered during the war and died of natural causes or that he was a merchant seaman who had overstayed his visit to Australia.

The man’s body was embalmed to give police more time to identify him, and a plaster cast—or death mask—was made of his face, as a physical reminder of who he was before he was laid to rest in an Adelaide cemetery under a headstone reading only “the unknown man”.

The Somerton Man’s body was exhumed last year as part of Operation Persevere, which seeks to put a name to all unidentified remains in South Australia, but forensic experts have still not been able to identify him.

“For more than 70 years people have speculated who this man was and how he died,” Vickie Chapman, then-attorney general of South Australia, said in a statement last year.

“It’s a story that has captured the imagination of people across the state, and, indeed, across the world—but I believe that, finally, we may uncover some answers.”

The story of the “unknown man” made headlines across Australia and New Zealand, and his fingerprints and photograph were sent around the world, including to England, America, and English-speaking countries in Africa, his coronial inquest heard. A letter dated January 1949, signed by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, confirmed the U.S. had found no match for his fingerprints in its files.

“I think the immediate cause of death was heart failure, but I am unable to say what factor caused heart failure,” said Robert Cowan, a government chemical analyst who examined samples taken from the body.

South Australia Police Detective Superintendent Des Bray previously said many theories had been advanced over the years, but “the truth of it is, nobody knows”.

“There was talk about whether he was a Russian spy, whether he was involved in the black market, whether he was a sailor,” he said.

“People did their best in the past, everybody did everything they could to solve the case, but they haven’t been able to.”

Speaking at the grave site ahead of the exhumation last year, Det. Supt Bray said it was “important for everybody to remember the Somerton Man is not just a curiosity, or a mystery to be solved.”

“It’s somebody’s father, son, perhaps grandfather, uncle or brother, and that’s why we're doing this and trying to identify him,” he continued.

“There are people we know that live in Adelaide, they believe they may be related,” he said.

“And they deserve to have a definitive answer.”

The Somerton Man was embalmed so as to give investigators more time to work out who he was.

Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/South Australia State RecordsForensic Science SA Assistant Director Anne Coxon said a range of different DNA techniques would be used, but cautioned that “we may or may not be successful”.

“The fact that the remains have also been embalmed [72 years ago] adds another complication, and that’s because the embalming fluid can break down the DNA,” Dr Coxon said ahead of the exhumation.

“At this stage, it’s difficult to put a timeframe on it.

“Even if we do find DNA present, we may not actually find a match. It will depend on who’s on the databases that we’re looking at and what information can be extracted from the comparison that’s made.”

Professor Derek Abbott recently commissioned Canadian virtual reality artist Daniel Voshart to reconstruct what the Somerton Man may have looked like when he was alive.

Professor Abbott, who is a specialist in biomedical engineering at the University of Adelaide, was put in touch with Voshart by Dr Colleen Fitzpatrick, a pioneer in forensic genealogy in the U.S. Using artificial intelligence software, Voshart combined the physical descriptions of the Somerton Man with the autopsy photos and images of the plaster bust.

The striking images bring to life the face of a man whose name nobody yet knows and whose life and death remains one of Australia’s most compelling mysteries—and an open police investigation.

Uncovering the Somerton Man’s true identity has also become somewhat personal for Professor Abbott who has spent years researching the case and believes there could be a family tie.

During the course of his investigations, Professor Abbott met his now-wife Rachel Egan, after sending her a letter to explain why he thought she may be the Somerton Man’s granddaughter. After a single dinner dominated by talk of death and DNA, the pair decided to marry and went on to have three children, CNN reports. “Whether he’s related to one of us or not, we’ve kind of adopted him into our family, anyway, because it’s him that has brought us together,” Professor Abbott said.

A portrait of the Somerton Man—who the children know as Mr S or Mr Somerton—now hangs above their playroom door.

“His cause of death isn’t really what is of interest anymore. It’s more who was he and can we give him his name back?”