On Thursday night the Songwriters Hall of Fame will induct Robert Hunter and Jerry Garcia (along with Willie Dixon, Bobby Braddock, Toby Keith, Cyndi Lauper, and Linda Perry) as new members.

A look at the Hunter-Garcia duo’s story seems called for—it’s a fairly remarkable history.

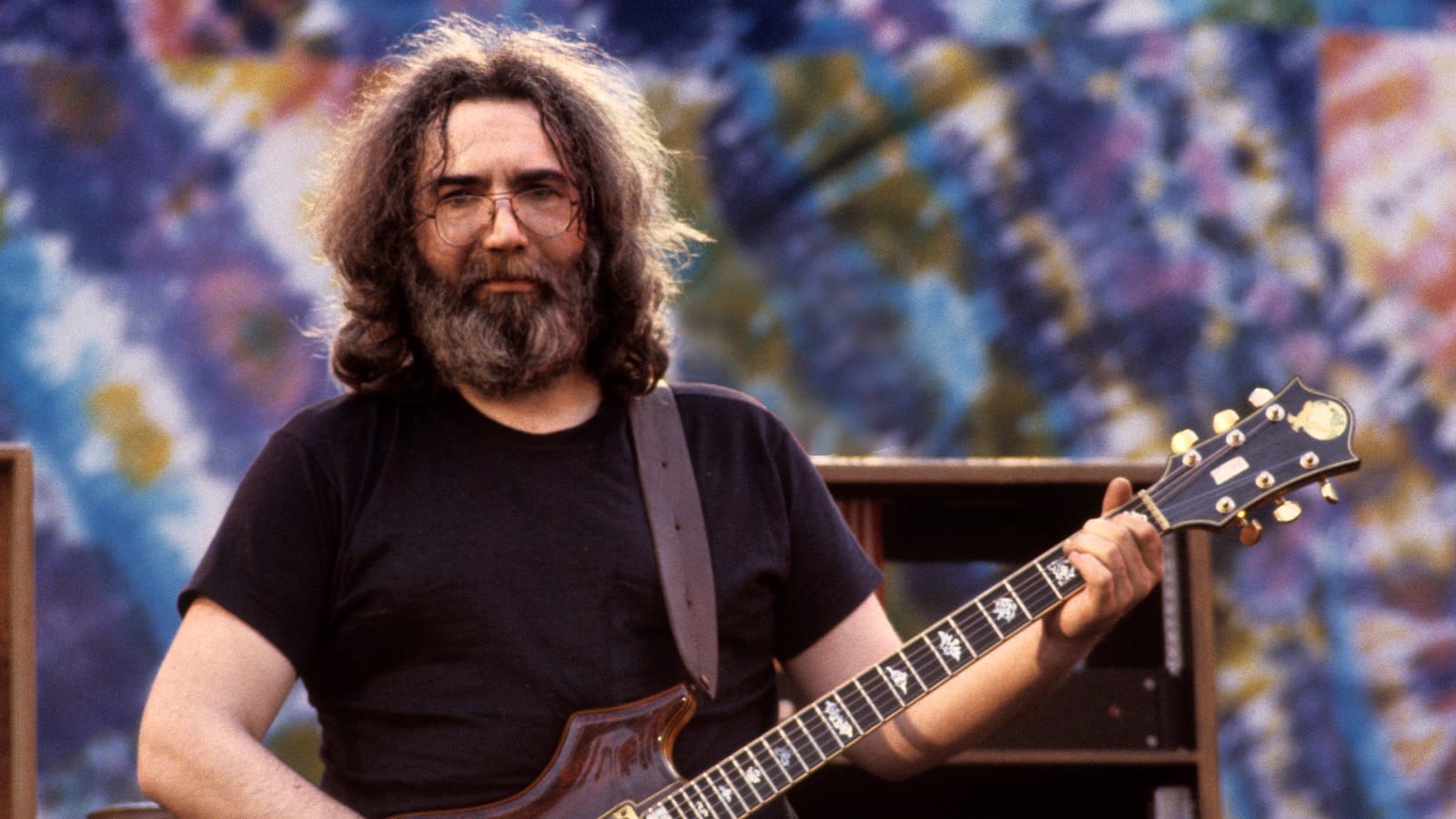

Given the stylistic diversity each band member brought to the early Grateful Dead—a lead guitarist/vocalist whose playing was informed by bluegrass banjo, a folkie rhythm guitarist/vocalist, a genuine blues-singer/harpist, an R&B drummer, and a bass player who’d played Stan Kenton-style trumpet and then studied Stockhausen and Berio—they were blessed from the beginning with the possibility of being truly interesting. But they developed their potential for greatness as a band when they reached out to their proto-novelist friend Robert Hunter and made him their primary lyricist.

With the single exception of Bob Weir’s tribute to Neal Cassady, “The Other One,” the Dead’s early original lyrics tended to be superficial and easy. Garcia would become one of the outstanding guitar players and songwriters of his generation, but he had a very limited talent for lyrics, and admitted later that he simply put down whatever came to mind—see, for instance, “Cream Puff War”: “Wait a minute, watch what you’re doin’ with your time / All the endless ruins of the past must stay behind, yeah.”

It was his and the Dead’s great good fortune that his bluegrass buddy Hunter had all the talent they’d need.

A descendant of Robert Burns, Hunter was born near San Luis Obispo, California, in 1941. His alcoholic father deserted the family when Robert was 7, and he spent several years in foster homes before he was reunited with his mother. Deeply scarred by it all, he took refuge in books, and by the age of 11 he had already written a 50-page fairy tale. His mother remarried at that time, and his new stepfather, Norman Hunter, worked in publishing, passing on writing lessons that Hunter took to heart.

In his teens he began to play musical instruments, and when his family moved to Connecticut he became the trumpet player in The Crescents, a band that somehow managed to combine Dixieland and rock ’n’ roll. After a desultory year at the University of Connecticut, he returned to Palo Alto, where he’d attended high school, and soon met Jerry Garcia. Naturally, they swiftly proceeded to play music together.

They spent their time hanging out in what passed for Palo Alto’s 1961 bohemian community—St. Michael’s Alley coffeehouse, Kepler’s Bookstore, and the Peace Center—most of the time with guitars in their hands, particularly in the back of Kepler’s. Roy Kepler was a part of the pacifist group that founded Berkeley’s KPFA and the Palo Alto Peace Center, which would become an early training ground for Joan Baez. He admired Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore, the first paperback bookstore in America, and opened Kepler’s in explicit homage. Fortunately for Hunter, Garcia, and friends, he was also a lovely and tolerant man who didn’t mind having young wastrels playing music in the corners of his store.

Soon after they met, Hunter and Garcia attended a party where Robert found a guitar. He got through perhaps half a song before Garcia grabbed it with the comment, “Hey, give me that.” Garcia would always be the dominant player, but they remained musical partners, playing in public for the first time as “Bob and Jerry” on May 5, 1961, at the Quaker Peninsula School’s graduation. Given Hunter’s limits as a guitarist and Garcia’s ravenous drive to get better, the duo didn’t last terribly long, but they remained friends.

As Garcia dove deeper into old-time music and then into bluegrass, Hunter would come along, playing mandolin in the Thunder Mountain Tub Thumpers and later the Wildwood Boys. But Hunter spent more and more of his time with words. By 1962 he was writing a never-published roman a clef, The Silver Snarling Trumpet. I suppose I’m one of the few people ever to have read it, and you can see in it not only his youth but also his skill at storytelling and his fantastic ear for dialogue. As the ’60s careened along, Hunter continued to write during a period in which he also ingested a fair amount of amphetamine. Consequently, one result would be blank verse hallucinations that he would transmute into the lyrics of the Dead song “China Cat Sunflower.” Through 1967, he was a soul somewhat adrift, eventually landing in New Mexico.

Back in Palo Alto, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, a blues harpist/vocalist who’d been part of the same folk scene as Jerry and Bob, listened to the Rolling Stones’ first album and told Garcia, “We can do this.” He was right. By May 1965 they were the Warlocks, with Garcia on lead and vocals, folkie Bob Weir on rhythm guitar, the local hotshot R&B drummer Bill Kreutzmann, and the jazz trumpeter/avant-garde composer Phil Lesh on bass. That fall, they landed what became a six-week residency in a local bar called the In Room.

Like every baby band of the era, they began by covering current hits, making a specialty of being the first group on the Peninsula to learn the latest Rolling Stones songs. From the beginning, they diverged from the customary path of cover bands because they used their repertoire—the Stones, the Lovin’ Spoonful, Dylan, any number of classic blues songs—as a starting point for improvisation. Lesh and Garcia, who particularly influenced this decision, had spent a lot of time listening to John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and they were never inclined to play any song note-for-note. The LSD they were taking—they would drop out of the bar band world and experience the Acid Tests for some months in late 1965 and early 1966—encouraged this development, as well. Now the Grateful Dead, they were a band on a quest, and for a long time, they focused on developing their playing rather than thinking of writing original songs.

Since their goals were idealistic and meta-artistic, they weren’t in any particular hurry to sign with a record company, another reason they were very slow to come up with original material. When they finally came to record their first album, released in March 1967, it had only two originals; the slight “Cream Puff War” and the bouncy but limited “Golden Road (to Unlimited Devotion).” But now that they’d bitten the bullet, signed with a record company, and released a record, their paucity of originals had to be confronted.

That summer they started working on a Pigpen song called “Alligator,” which included lyrics by Robert Hunter, then living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Garcia reached out and told Hunter about the new song and suggested he come home, which Robert was happy to do. After more than a few misadventures, he pulled into San Francisco, where he was met by Lesh, who drove him up to a dance hall in the tiny hamlet of Rio Nido, on the Russian River north of the city.

Sitting in a nearby cabin, he listened to them jam on a simple figure set against a line, an endlessly flexible musical key that could go anywhere and open any melodic lock. He had always been, he later said, “the most lucid hallucinator in the group,” and now he proved it. He quickly scribbled down lyrics, and at the break showed them to Garcia. “Yeah, that scans, that works.”

A few days later, he sat writing in Golden Gate Park. A passing hippie noticed him at work and handed him a joint with the comment, “Maybe this will make things easier for you.” Hunter smiled, toked, and replied, “Thanks a lot, man. In case anything comes of it, this is called ‘Dark Star.’”

Hunter had found his calling. The spare, crystalline lyrics to “Dark Star,” complete with a respectful echo of the opening of T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”—“Let us go then, you and I,” versus Hunter’s “Shall we go, you and I, while we can”—catalyzed the song and helped make it great.

Ironically, the Dead found “Dark Star” impossible to record in the studio, so Hunter was pretty much absent from their second and most highly experimental album, Anthem of the Sun, which was largely a collectively written affair. Their next opus, Aoxomoxoa, saw the writing combination of Garcia and Hunter step out, writing every song.

Though there are at least two absolute winners in the album, it was still something of a training ground for them. Garcia would comment that “Cosmic Charlie” was “rangy” and difficult to sing. “St. Stephen,” though magnificent in its opaque grandiloquence and medieval imagery, was superb when done just right, but rhythmically tricky and demanding. “Mountains of the Moon” was an astonishingly romantic minuet, but perhaps because the original version included a harpsichord, they rarely performed it (although they do so wonderfully on Playboy After Dark).

“Dupree’s Diamond Blues” rewrites a classic rounder ballad called “Betty and Dupree,” while “Doin’ That Rag” was another odd song that juuust missed.

Ironically, the most successful song on the album, at least measured by the way it entered the repertoire and stayed there to the end, was “China Cat Sunflower,” which combined neo-Carrollian (very much psychedelic Cheshire cat) imagery with a rhythm that seemed just a smidgen eccentrically off-center. Or perhaps Hunter explains it when he recalls how he felt when he wrote it: “I had a cat sitting on my belly at one point, and followed the cat out to—I believe it was Neptune, but I’m not sure—and there were rainbows across Neptune, and cats marching across this rainbow.”

Really, they were just getting started. Aoxomoxoa was released in June 1969, but something special had already taken place. In April, Hunter and his lover Christie Bourne moved in with Jerry, his wife Carolyn “Mountain Girl” Garcia, and Sunshine, her daughter with Ken Kesey. The intimate propinquity of that period brought their songwriting to an entirely new level. The band would spend the year playing the most remarkable improvisational psychedelic jazz-rock fusion music ever (in April 1970, Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew band opened for them, and while the Dead were embarrassed, it was appropriate). But bit-by-bit, as Hunter and Garcia introduced their new songs over the course of the year, the Grateful Dead would transform itself from an experimental fusion outfit into a full-range ensemble that could play anything—and did.

Our collective memory of these songs is deeply colored because they would be recorded early in 1970 on an album called Workingman’s Dead, which would be spare, simple, and modeled after the Bakersfield sound of Buck Owens and Merle Haggard. Although this came in the wake of The Band’s Music from Big Pink, the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and Crosby, Stills, and Nash’s eponymous first album, the real reason for the sound of Workingman Dead was that in January 1970 the Dead owed Warner Bros. $250,000 in studio costs after recording three albums that had sold poorly. They simply had no other option except to record something simple.

Besides, it suited the material. And what material.

One morning in the spring, Hunter had come downstairs and handed three new songs to Garcia, who was running scales in his customary position in front of the television. Jerry allowed as how he’d look at them later. Miffed, Hunter replied, “Garcia, if you think I’m living here for the pleasure of your mythical sunny personality—I’m here to write songs. Do you want to write songs or not?” “Oh!” Garcia began to read the lyrics, and quite soon thereafter had finished the first of them, “Dire Wolf.”

Hunter had stayed up one night with M.G. to watch The Hound of the Baskervilles, and it rewarded him with extraordinary dreams. As he later commented, he had a “tunnel into (his) subconscious” and an ability to “touch that dreamspace.” He transcribed his dreams and had the song.

“Dire Wolf” has a chorus where “the boys sing ’round the fire,” but this is no simple cowboy song. The “Dire Wolf” is in fact a close kindred to Melville’s whale, a wolf out of the white void that is not a place but no-place, where rests our doom. The song’s narrator is what came to be perceived as the fundamental Grateful Dead character, a plain workingman. Our man sits down to a card game, but the deck is stacked, and we realize that he’s playing cards with Death, just as in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The Wolf is presumed evil, but in Robert Hunter and the Dead’s post-modern world, that doesn’t make him bad, exactly. There he is, and you might as well see if you can enjoy his company.

A pattern was set. The two of them began turning out brand new songs that were somehow American and Western (as in cowboy) folk tunes without being explicitly from any region, something similar to the way One Hundred Years of Solitude is universal and removed from any specific time or place. They were in fact so universal that many of the songs truly became folk songs, i.e., disassociated from the actual creators. “Friend of the Devil,” for instance, while indubitably a Dead tune, can be heard almost anywhere people pick up guitars. It or, say, “Ripple” do not need to be tied to the name Grateful Dead—they’re simply part of the American canon in a way that is true of very few modern songs.

One of Hunter’s more rewarding moments came when an Appalachian man heard the Grateful Dead sing “Cumberland Blues,” a rare example of a Hunter lyric attached to a specific region. It sounded so authentic that the man assumed that it was a traditional local song, and the idea of filthy hippies from San Francisco singing it revolted him. Hunter didn’t bother to correct him, but savored his odd, inverted critical triumph.

“Uncle John’s Band” was more typical in its universal American-ness. What was particularly fascinating about it was how Hunter came to write it. The band gave him a 40-minute tape of the band playing the key changes in the song, over and over, in precisely the way they played everything in mid-1969, which is to say loudly, and with a sizzling, ferocious drive that does not remotely resemble the essentially acoustic feeling of the album version.

Yet the lyrics are utterly consonant with that feel—there’s a soft Americana to the “buckdancer’s choice,” the Revolutionary War images, the violin, the crow, the morning sun, and the wind. Since, like almost everyone not in the band, I’d first heard the song on the album, the perfect agreement of lyric and sound seemed natural to me. But when Hunter lent me the original work tape, I was flabbergasted. How, I wanted to know, did he hear that in the tape they’d given him? I asked Garcia about it, who chortled, “Well, you had to be there … And, also, you had to be able to get all the intent. You know what I mean? Which is a lot of the communication that I would communicate to Hunter.”

They’d become musical partners in an astonishing way. Out of friendship, common experience, Hunter’s extraordinary capacity for empathy, and his sterling ability to translate that into lyrics, he had become able to close the circle of the song, to add words to music, and help the members of the Grateful Dead fulfill their promise.

I hasten to add that Hunter did far more than act solely as Garcia’s musical amanuensis. On the next album, American Beauty, he worked with Pigpen (“Operator”), Lesh (“Box of Rain”), Bob Weir (“Sugar Magnolia”), and both Lesh and Weir (“Truckin’”). Great songs, these, and both Lesh and Weir will acknowledge that these songs (along with, for instance, Weir’s “Playing in the Band”) are among the best things they’ve ever done.

Eventually, Hunter would decide he could only work with one musician, and handed off Weir to their friend John Perry Barlow; Lesh worked with both Peter Monk and Bobby Petersen, but didn’t write so very many songs thereafter.

But after the dust settles, the Hunter-Garcia masterpieces from American Beauty—“Ripple,” “Attics of My Life,” and “Brokedown Palace”—will make you cry, pray, or simply quiver as the hair on the back of your neck stands to attention. A hymn, a love song that is also a prayer, and a benediction—there’s nothing like these three songs in rock ’n’ roll, and that’s just on one album.

They would work together another 25 years and write dozens more tunes together, but I don’t feel the need to be complete. Instead, I’m going to talk about just two of them.

One stormy winter day in late 1976/early 1977, Garcia was driving home to Marin County from the East Bay across the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge. At the same time, Hunter looked out on the same turbulent water from his home at China Camp, near Novato. Lightning flashes on the waves set him to writing.

He started with the archetypal outline laid down in the English ballad “Lady of Carlisle,” in which a cautious sailor and an impetuous sailor compete for the favors of the lady. Beginning with an invocation to the muse—“Let my inspiration flow in token rhyme suggesting rhythm”—he scribbled madly for three days, winding up with a thousand words on eight pages.

As Hunter wrote, Garcia looked out over the water from the bridge and began to hear a song in his head. Racing home, he turned on a tape recorder and swiftly recorded the chord changes. He fiddled with it for a day or two to be sure, then took himself to Hunter’s house, where he found lyrics that seamlessly matched his song. Taking the first page, half the second page, and the last page, he went off to the band and had them work out their own parts. With stunning quickness they had a new tune—rather, they had what I called in A Long Strange Trip “a majestic, rolling, near-symphony.”

The next month they played their first show of the year at Swing Auditorium in San Bernardino, and opened the show with their brand new magnum opus, “Terrapin Station.” Hunter was there, and as he wrote much later, it was so good that it made him feel “about as close as I ever expect to get to feeling certain that we were doing what we were put here to do.” It is about the warring elements in our lives, about desire, about the goals that we all pursue, about life. It’s quite wonderful, really.

The last song is in some ways the lost song. It was never recorded in a studio—when they tried, Garcia simply lacked the energy or desire to play. It debuted on February 22, 1993, part of the troubled last two years of Garcia’s life, when his inability to address his failing physical health seemed to cloak him in darkness.

The year before, he had rekindled a relationship with Barbara “Brigid” Meier, a woman he’d known when he was 19 and she perhaps 16, back in sweeter, simpler days in Palo Alto. It seemed a new beginning to his friends, and a happy one. Robert Hunter was particularly energized by it. The three of them had been close some 30 years before, and seeing Jerry and Brigid together sent him, of course, to the writing table.

The result was “Days Between.” It came on an inglorious night for the band. They weren’t playing all that well, and even the sound seemed to be off the mark. In the middle of the rather ordinary, a stunningly beautiful rose bloomed. Garcia’s music for it was a somewhat unusual drone that did nothing except set off Hunter’s lyrics, words that were simply spectacular in their skill and glorious in their ability to make every person over 50 think about the chasm between youth and age.

There were days and there were days and there were days between Summer flies and August dies the world grows dark and mean Comes the shimmer of the moon on black infested trees the singing man is at his song the holy on their knees The reckless are out wrecking The timid plead their pleas No one knows much more of this than anyone can see anyone can see…

The Songwriters Hall of Fame has chosen very wisely.