Rolling Stone, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary next month, was born in San Francisco amidst an emerging counterculture that, for better or worse, deeply affected how millions of Americans lived. Under the inspiration of its 21 year old founder Jann Wenner the new publication sought to ride the 60s zeitgeist to fame and fortune.

San Francisco and Berkeley were the seedbed of the nation’s political and cultural radicalism, beginning with the 1964-65 Berkeley Free Speech Movement (which Wenner participated in as a freshman) the hippie, psychedelic community in the Haight Ashbury neighborhood and the 1967 Summer of Love. Revving up the soundtrack were hundreds of new rock and roll bands springing up all over the Bay Area. On any given night young people could toke up and for a couple of bucks walk into the Fillmore or Winterland ballrooms to groove to performers like Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin and Santana.

Adventurous young people were flocking to the big swinging party from all over the country. As one of that year’s hit songs put it:

If you're going to San Francisco

Be sure to wear some flowers in your hair

Despite his identification with the counterculture, particularly the drug scene, Wenner disdained the political radicals spearheading the anti-war movement, firebrands such as Tom Hayden, Jerry Rubin and Abie Hoffman. Instead, in the inaugural issue of Rolling Stone Wenner promised that his new magazine would celebrate “the magic [the music] that can set you free.” With every subscription to the new magazine Wenner offered a complimentary roach clip.

The following year Wenner criticized the youthful anti-war demonstrators clashing with the cops at the Democratic Party convention in Chicago. In a front page editorial in Rolling Stone he opined that, “Rock and roll is the only way in which the vast but formless power of youth is structured, the only way in which it can be defined or inspected. . . [and] It has its own unique morality.”

For the next decade Wenner would continue using Rolling Stone to champion the notion that the music itself would lead to personal liberation and a better world. Nothing like that happened, of course, and could never happen. Yet there’s no doubt that the sex, drugs and rock and roll revolutions of the 60s made Jann Wenner very famous and very rich.

By the time he was forty years old Wenner owned a fuel guzzling Gulfstream II jet seating 10 passengers and flew it around the country on a whim. He purchased stately mansions, travelled through Gotham’s streets in chauffeured limos and vacationed with the lords of Hollywood on luxury yachts all over the world. He hobnobbed with Jackie Kennedy and even had a brief fling with daughter Caroline. Eventually Wenner turned his rock and roll magazine into a media auxiliary for the Democratic Party and became a confidant of presidential candidates Al Gore and John Kerry.

Like other media moguls, Wenner’s spectacular success made him quite arrogant. He became so convinced that he was untouchable, that his stardom would never fade, that in 2013 he enlisted a New York Magazine journalist named Joe Hagan to write the definitive Jann Wenner story, projected to come out in time for Rolling Stone’s 50th anniversary celebrations. Wenner sat for over 100 hours of interviews and encouraged everyone in his circle to speak freely to Hagan. He also granted the biographer unfettered access to his vast archive of personal letters, notes and documents. (Wenner never threw anything out.)

Clearly Wenner misjudged his intended Boswell. According to the New York Times, the publisher now feels betrayed by Hagan and had the author disinvited from a planned joint appearance at the 92nd Street Y. After reading Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine, you can see why Wenner is so upset. Hagan’s let-it-all-hang-out narrative, filled with intimate and sometimes ugly accounts about Wenner’s personal life and business practices, appears at a time when the publisher is reportedly desperate to sell Rolling Stone. It doesn’t help when your semi-official biographer concludes that there is “a striking likeness” between you and Donald Trump – “deeply narcissistic men for whom celebrity is the confirmation of existence.”

Let’s first set aside Hagan’s titillating revelations about Wenner’s sexual escapades— struggles as a young man with closeted homosexuality, serial, extra-marital affairs with men and women, and the extended bisexual, ménage a trois Wenner and his wife conducted with Rolling Stone’s most famous photographer, Annie Leibovitz.

These episodes are generating much media attention and will sell books. Still, who cares about Jann Wenner’s private, consensual sex life? It would be unfortunate if such trivia (one more chapter in Sex Lives of the Rich and Famous) distracts from what’s truly meaningful about this essential American biography for our times. Hagan has produced a dark tale about greed and ambition and the pervasive celebrity culture that, according to the author, has become “the framework of American narcissism.”

Hagan’s reporting is as vivid as the work of some of Rolling Stone’s most famous writers, including the avatar of the “new journalism” Tom Wolfe and “gonzo” journalist Hunter Thompson. The book sometimes reads like a novel and had me thinking of notorious fictional equivalents to Hagan’s main character – perhaps Budd Schulberg’s Sammy Glick, or Stendahl’s Julien Sorel, or Gordon Gekko from the movie Wall Street.

I also read the book with a personal shiver of recognition. That’s because I was present at the creation of Rolling Stone in the fall of 1967. At the time I was one of the senior editors of Ramparts, the most widely read anti-war magazine in the country. I briefly met Jann Wenner during the free speech protests on the Berkeley campus. He had also written about the local music scene for Sunday Ramparts, a short- lived weekly supplement to our slick, commercial monthly. Ramparts was then at its peak influence, with a national circulation of 200,000, an unheard of number for an avowedly radical publication.

One October night I was working late in the Ramparts office in the North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco, when I detected the pungent smell of marijuana. I wandered back to the composing room (no computer generated layouts in those days) and discovered Jann Wenner puffing away on a joint while working on the inaugural issue of Rolling Stone with the help of Ramparts’ production director, John Williams.

I reamed out Wenner for his reckless behavior. It’s not that I had moral objections to his personal choice of inebriants. But I reminded him that Ramparts had recently broken two big stories revealing C.I.A. clandestine operations, including an article of mine exposing the agency’s funding of the National Student Association. The four top editors had recently burned our draft cards and put a photograph of our stunt on the cover of the magazine and in ads running on the sides of New York City buses. We were then served with subpoenas to a federal grand jury for possible prosecution (although the Justice Department eventually backed off.) We were sure that Ramparts was under surveillance and that the national security authorities would love to shut us down for any legal infraction, large or small.

Wenner said I was being paranoid. I’m sure he also thought that I was an old fogey. (After all, I was 31 years old and one of the shibboleths of the counterculture was that “you can’t trust anyone over 30.”) To me he appeared flippant and somewhat ungrateful, considering that we were generously helping him start up his little broadsheet. We not only provided the fledgling editor with free office space and the services of our art director, but he copied his paper’s design and layout from the Sunday Ramparts.

The truth is that I didn’t hold this angelic looking 21 year old in the highest regard. I thought his publishing project was a pipedream, another in a long list of underground, hippie papers that proliferated like mom and pop stores in the Bay Area and then quickly went bust.

How spectacularly wrong I was. Within a year the mighty Ramparts had flamed out in chapter eleven bankruptcy proceedings, in large part because our brilliant, yet hopelessly irresponsible editor Warren Hinckle couldn’t stop spending money he didn’t have. As Ramparts fell from the publishing heights, Rolling Stone took off like a meteor, reaching a national circulation of 200,000 by early 1970. The “Wenner kid” (that’s what the Ramparts editors called him) turned out not so reckless after all, at least not in the realm of business and marketing.

Given this background I was fascinated by Hagan’s detailed account of just how the brash young man on the make was able to beat the publishing odds and get Rolling Stone off the ground on a shoestring budget.

Wenner showed a genius for discovering new talent from the Bay Area’s surplus of young writers and photographers willing to work for pennies (or shares of an apparently worthless media company) and then cleverly matching those journalists to the hottest new rock and roll stars. His most important find was an aspiring young photographer named Annie Leibovitz, who as an 18 year old had joined the countercultural pilgrimage to San Francisco from Waterbury Connecticut.

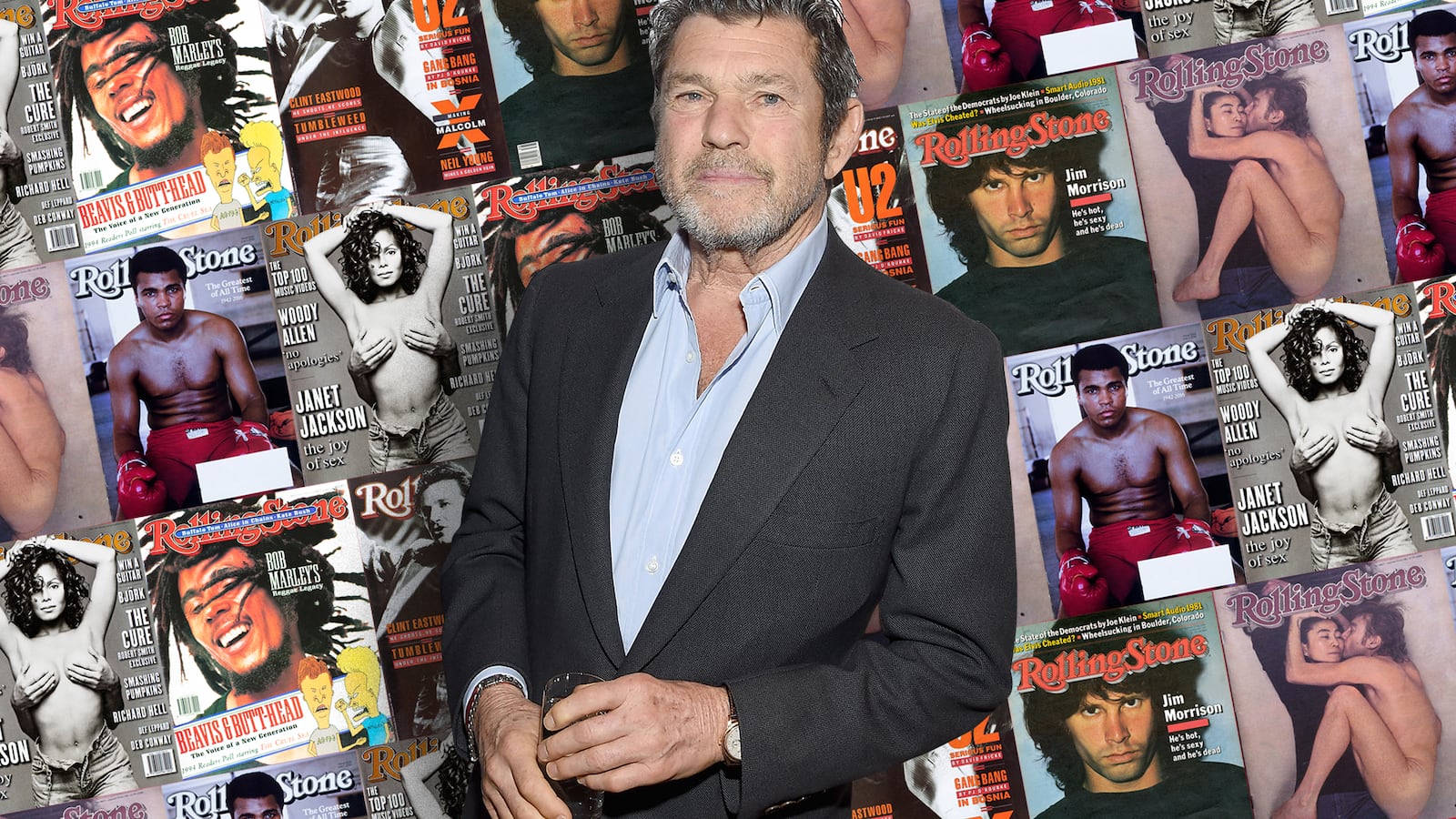

Much credit for the initial breakthrough also belongs to Wenner’s girlfriend (soon to be wife) Jane Schindelheim, a vivacious 20 year old expatriate from New York’s Laguardia High School for the Arts, whom Jann had met at Ramparts where she worked as a receptionist. Jane worked 24/7 to keep the bi-weekly running on time despite the haze of drugs permeating the cramped and moldy offices in a run-down office building. She controlled the budget like a tight fisted accountant, checking Jann’s Hinckle-like tendencies to spend other people’s money. Rolling Stone’s greatest innovation was its spectacular covers. Annie Leibovitz’s intimate, sexed up photographs of the superstars of the rock world helped make the magazine catch fire on newsstands around the country, at least those areas where young people were tuning in to the new popular music. Leibovitz’s covers, as Hagan puts it, “became the prime sales pitch for selling records and the prime sales pitch of Wenner’s magazine.”

Not all the rock and roll stars and Hollywood celebrities who graced Rolling Stone’s covers were created equal in Jann Wenner’s eyes. He reserved exclusive space in Rolling Stone’s firmament for the holy trinity of John Lennon, Mick Jagger and Bob Dylan. To Wenner they were Gods from Olympus who exemplified the power of rock and roll to remake the world. He succeeded in getting close to each of the legends and put them on the cover of Rolling Stone as often as he could.

Yet Wenner also betrayed his friends whenever it served his purpose or Rolling Stone’s bottom line. For example, in 1971 Wenner devoted two issues of the magazine to a very long and amazingly intimate interview with John Lennon that had a huge impact for all concerned. It broke up the Beatles, made international news and jump started a financial breakthrough for Rolling Stone. But Wenner, whose middle name might as well have been Excess, couldn’t get enough. Despite Lennon’s vehement opposition, Wenner republished the interviews as a separate best-selling book. John Lennon never spoke to him again.

Art Garfunkel, another best pal who felt betrayed by Wenner, told Hagan: “He [Wenner] leads with his appetites – I take, I see, I have. If he puts his arm around your back, there might be a dagger there.”

Wenner had a similar off again, on again fractious relationship with Bob Dylan. More than any other artist, Wenner believed, Dylan was the ultimate avatar of Rolling Stone’s philosophy of rock and roll music as liberation. The young troubadour was the real thing, the rebel, non-conformist writer of protest songs and how “the times they are a-changin.”

Unfortunately for Wenner, Dylan would have none of it. In an interview with music critic Nat Hentoff published in the New Yorker two years before the launch of Rolling Stone, Dylan explicitly rejected the idea that he was any kind of spokesman, political or otherwise, for the rising generation.

Wenner refused to give up the ghost. His obsession with Dylan as some sort of leader with a message for how young people should live their lives in America led to the following almost laughable exchange, part of an interview published in Rolling Stone in November, 1969.

Wenner: Many people – writers, college students, college writers, all felt tremendously affected by your music and what you’re saying in the lyrics.

Dylan: Did they?

Wenner: Sure. They felt it had a particular relevance to their lives. . . I mean you must be aware of the way that people come on to you.

Dylan: Not entirely. Why don’t you explain it to me.

Wenner: I guess if you reduce it to its simplest terms the expectation of your audience – the portion of your audience that I’m familiar with -- feels that you have the answer.

Dylan: What answer?

The truth is that Wenner’s dream of redemption through rock went completely over the heads of the young readers who came to the magazine because they loved the new music, the celebrity write-ups, the great cover photographs, as well as the occasional inspired journalism by the likes of Hunter Thompson and Tom Wolfe.

**********

By 1977 Wenner decided that San Francisco was no longer where it was all happening. The music scene was dying, the Haight Ashbury was a slum and the city by the bay suddenly seemed provincial. For all the hype about rock and roll music as liberation and Rolling Stone’s sometimes excellent journalism, the magazine had become a show business enterprise. As Hagan writes, “For Wenner, idealism was never the enemy of money. ‘It was a false dichotomy,’ said Wenner. ‘Well, it’s America! Rock and roll is America.’”

In pursuit of record company advertising Wenner began filling parts of the magazine with music reviews that were essentially re-writes of the record companies’ promotional materials. According to Hagan, Wenner went so far as to write his own blurbs into the copy turned in by reviewers, without even informing the writers. He allowed favorite performers to edit their own interviews before they appeared in print. And he fired those writers who wouldn’t toe the party line about which artists deserved favorable reviews. Among those who were canned or just walked away in disgust were legendary rock writers Lester Bangs and Greil Marcus.

By its 10th anniversary Rolling Stone was generating $30 million in profits. The magazine continued to boast about its journalistic integrity and the independence enjoyed by its writers, but it was also building income by colluding with the record industry in a form of payola.

Since it was now all about show business it also became obvious that the place to be was either Los Angeles or New York. In 1977 Wenner moved Rolling Stone to the Big Apple, the center of media and finance. By that time Wenner had put aside the “music is the revolution” ideology. Even he must have recognized that there was a certain dissonance in pontificating about liberation from your plush offices overlooking Fifth Avenue.

Wenner had also embraced a new vehicle for achieving his ideal of social liberation. Incongruously, it was the east coast, liberal wing of the Democratic Party. In the Washington Post, Wenner’s most famous writer Hunter Thompson summarized the publisher’s new path to glory: “He decided it was hipper to hang out with politicos than with rock ‘n rollers. There’s no doubt that he wants to run for office. I mean, isn’t that the ultimate power trip?”

Hagan reports that Wenner was then also having conversations with colleagues and friends about -- believe it or not – running for President. He even promised his numero uno writer Thompson that he could be press secretary or secretary of state in a Wenner administration and was “developing the outlines of a stump speech,” according to Hagan. In what must rank as the funniest line in the book, Wenner responded to a reporter inquiring about his political intentions: “I think the vanguard of young people is interested in restoration in the United States of integrity and truth as the operating method and way of life rather than hypocrisy.”

I’m sure that Hagan has accurately reported these send-in-the- clowns moments; his sources throughout the book are impeccable. Which also means that Hagan’s comparison of Jann Wenner’s character to Donald Trump is no way fanciful.

Thankfully for the country, Wenner stepped back from trying to grab the brass ring for himself. Instead, he spent a lot of his magazine’s money to create a little political machine and media operation in order to become a player within the Democratic Party.

His first move was hiring old JFK hand Richard Goodwin to run a Washington bureau for Rolling Stone that was less a journalistic enterprise than a political one. Wenner told Goodwin he was ready to spend close to $1 million “to make his [Wenner’s] mark in Washington,” according to Hagan, and now announced that “politics is the rock and roll of the 1970s.” Wenner soon tired of Goodwin, accused him of spending too much of Rolling Stone’s money (a classic case of the pot calling the kettle black) and fired him

Rolling Stone went all in to get Jimmy Carter elected president and Wenner assigned Hunter Thompson to write a series of hagiographic articles about the peanut farmer from Georgia. It was the end of Thompson as a serious, independent journalist. After Carter’s defeat in 1980 Rolling Stone mobilized its resources (and further devalued its journalistic credibility) to get behind every Democratic candidate for president.

One of the most unsettling parts of Hagan’s book is that even as Wenner was becoming an influential player in the Democratic Party he was also running a virtual drug den at his home and in the Fifth Avenue offices of Rolling Stone. It’s not just that, as Hagan writes, Wenner “consumed drugs like a Viking.” With his easy money, Wenner became an enabler, a pusher really, ensnaring lots of people in his circle into life threatening drug dependencies.

In precise details Hagan describes how drugs were distributed at the Rolling Stone offices on the 22nd floor of 745 Fifth Avenue. The camera room was turned into “a de facto cocaine emporium, run by two employees who doubled as dealers.” Wenner distributed little folding envelopes filled with cocaine as bonuses to writers and editors for good work. At Rolling Stone parties, according to Hagan, “there were lines to the camera room, which Wenner manned like a velvet rope.” Polaroids were also taken of everyone who snorted cocaine in the camera room. Wenner seemed very proud of the efficiency of the operation, telling Hagan; “They would sit around, do a little blow, and they had a whole hall with like four hundred or five hundred Polaroids of all their visitors.”

In other words, Wenner’s drug emporium on the most glittering street in Manhattan was a virtual public event. At a time when the authorities were busting black kids further uptown for a couple of joints and ruining their lives, the rock and roll glitterati were free to commit multiple felonies. Although Wenner paid no price, his company’s cocaine operation left behind many casualties, including Annie Leibovitz who on two occasions overdosed and had to be rushed to emergency rooms. On one occasion she almost died on a hospital gurney.

Jann Wenner, who believed music would set us all free, was now contributing to one of America’s most serious public health problems. Moreover, it’s inconceivable that anyone in the rock mogul’s circle, including his friends in the Democratic party, didn’t know, more or less, about the drug business.

It’s too bad that Hagan seems unwilling to pass judgement on this debacle, which perfectly illustrates the observation years earlier by another kind of Democrat, Daniel P. Moynihan, about the consequences of “defining deviancy down” and the moral deregulation that he accurately predicted would infect all of American society.

In his conclusion Hagan quotes Will Dana a former Rolling Stone editor reflecting on Wenner’s legacy: “With Jann the question is, is he 51 percent good or 51 percent bad? I basically think he’s 51 percent good.”

Which prompts Hagan’s last line in the book: “And maybe that was good enough.”

Methinks Hagan should look back over his brilliant book and redo the math.

The most telling judgement on Wenner comes from Wenner himself. In responding to Hagan’s withering portrait of his character, Wenner offered this comment to the New York Times: “Rock and roll set me and my generation free musically, socially and politically. My hope was that this book would provide a record for future generations of that extraordinary time. Instead, [Hagan] produced something deeply flawed and tawdry, rather than substantial.”

Almost 300 years ago Samuel Johnson famously said that “patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.” In Jann Wenner’s version his last refuge is the preposterous claim that rock and roll set his generation free.