On May 8, the Pentagon announced that Abu Wahib was killed by a coalition airstrike in Rutba, Anbar Province, Iraq—the latest of several top-level ISIS officials to meet his end over the past two months, as the Obama administration has steadily ratcheted up its war on the Islamic State not only in Iraq and Syria, but elsewhere in the Middle East, in Afghanistan, and Africa. Omar-al-Shishani, believed to be the chief ISIS minister of war, was killed in an airstrike in early March, while Haji Iman, the leading ISIS minister of finance and reputed first lieutenant of ISIS chief Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, lost his life in a Special Forces commando raid intended to bring about his capture sometime around March 20.

To a degree unprecedented in American military history, the war against ISIS is a conflict spearheaded and orchestrated by the commandos, trainers, and advisers of the elite U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM). And the conflict against ISIS is only the headline-grabber in a much broader, underneath-the-radar struggle being waged by America’s shadow warriors to combat instability and looming crisis wherever American vital interests are at stake.

The Special Forces community’s increasingly robust presence around the globe is hardly restricted to deployments in active combat zones. Propelled by sharp spikes in demand worldwide for its unique expertise in irregular warfare and counter-terrorism, SOCOM appears to be well on its way to establishing what former SOCOM commander Admiral William McRaven calls its own “global network of likeminded interagency allies and partners.”

As of early 2016, almost half of the 7,500 Special Forces warriors overseas were posted outside the Middle East and Afghanistan, operating as both liaison and training teams inside more than 80 nations. Some of these teams are assigned to U.S. embassies, where they help to identify security risks, and provide advice to both the U.S. and foreign governments as to how these risks might be addressed before they reach crisis proportions. Others are attached directly to armies, militias, and police forces as trainers and advisers to buttress local security capabilities, and reduce the likelihood of interventions by conventional U.S. forces in the event of trouble.

Never before in American foreign policy has so much been entrusted to an elite cadre of unconventional war specialists.

In August 2014, McRaven, chief architect of the dramatic SEAL Team 6 raid that led to the killing of Osama bin Laden, declared, “We are in the golden age of special operations.” Today, signs abound that the secretive community of elite centurions from all four of the military services that SOCOM oversees has grown considerably more important than it was two years ago in the execution of the Obama administration’s national security policy as a whole.

In March, McRaven’s successor at SOCOM, Army General Joseph L. Votel, assumed the leadership of Central Command, by far and away the most strategically vital of the six regional commands in the American military. CENTCOM, of course, is responsible for overseeing operations throughout the Middle East, Southwest Asia, and North Africa, the epicenter of the Global War on Terror.

Secretary of Defense Ash Carter last December announced that a “specialized expeditionary force” of several hundred men would be sent to Iraq and Syria to buttress the U.S.-led coalition against ISIS there. Carter didn’t say so explicitly, but various sources confirm that the force is composed of “hunter-killer” counter-terrorist teams of Tier I special forces units—the Delta Force, SEAL Team 6, the 75th Ranger Regiment, and their supporting air assets. These commando units, said coalition spokesman Col. Steve Warren soon after Carter’s announcement, “will focus on high value individuals, high-value targets.” Their preference will be to capture militants, “because that allows us to collect intelligence” on their organizations’ structure and objectives.

Col. Warren left no doubt about the coalition’s mission: to help indigenous forces in the region to defeat ISIS on the ground, and retake the large swath of land it now controls in Iraq and Syria.

The efforts of this newly deployed commando task force are designed to complement those of an undisclosed number of Green Beret Operational Detachment-Alpha (ODA) units that have been in the war zone for many months already. These 12-man teams have extensive linguistic and cultural training, as well as wide-ranging military expertise, and they work “by, with, and through” the Iraqi Army, as well as a coterie of anti-ISIS militias in Iraq and Syria, providing tactical advice and forward air controllers to pinpoint ISIS targets for Coalition air strikes.

As of this writing the number of U.S. troops in Iraq and Syria, SOF, and conventional support troops combined hovers around 4,000, but the Pentagon has made no secret that it expects that number to increase steadily in the coming months. It’s a sure bet that a good percentage of these future deployments will be special operators of one sort or another.

Additional SOF deployments have recently been announced to combat ISIS-affiliated groups in Somalia, Libya, Cameroon, and several other African countries, even as SOF forces are actively combating a rising tide of Taliban and pro-ISIS insurgents in Afghanistan. U.S. commanders there claim to have killed or captured a hundred or more ISIS-affiliated fighters between late 2015 and early 2016, mostly in and around the politically sensitive border region with Pakistan.

After pledging to withdraw all U.S. troops from war-weary Afghanistan save for counter-terrorist units, President Obama announced late last year that 5,500 American troops would remain there through the end of his presidency in early 2017. Few close observers of the GWT would be surprised to see additional SOF deployments there before this year is out.

The arguments put forward by SOCOM for strengthening the sinews of its nascent global network strike many students of military affairs, including this one, as compelling. In a strategic environment where terrorist networks and proxy wars sponsored by both state and non-state actors abound, traditional diplomatic and military approaches to deterrence seem increasingly inadequate. Special operations teams are trained to implement unorthodox alternatives. Former SOCOM commander Votel, in remarks before the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities in March 2015, explained how the SOF global network can step into the breach in a world where U.S. national security institutions often work in a kind of “gray zone” between war and peace:

First, we conduct persistent engagement in a variety of strategically important locations with a small-footprint approach that integrates a network of partners. This engagement allows us to nurture relationships prior to conflict. Our language and cultural expertise in these regions help us facilitate stability and counter malign influence with and through local security forces. Although SOF excel at short-notice missions under politically sensitive conditions, we are most effective when we deliberately build inroads over time with partners who share our interests. This engagement allows SOF to buy time to prevent conflict in the first place.

Second, we integrate and enable both conventional forces and interagency, [e.g., the State Department, the Agency for International Development, NGO’s] capabilities. On a daily basis, SOF are assisting the [major regional combatant commands, such as CENTCOM] across and between their areas of responsibility to address issues that are not constrained by borders. When crises escalate, SOF develop critical understanding, influence, and relationships that aid conventional force entry into theater.

In a break with long precedent, Green Berets with specialized cultural and linguistic expertise now continue to support overseas operations in Africa, Asia, and Central America—mission planning, organizing information campaigns, and interpreting intelligence—even after they have returned to their home bases in the United States.

Meanwhile, the number of service members under SOCOM command had risen sharply from 45,000 in 2001, to 70,000 today. The SOCOM budget has mushroomed from $2.3 billion in 2001 to $6.6 billion in 2006 and to 10.8 billion in 2017. If the geographical scope of SOF deployments and increased clout of SOCOM within the halls of the Pentagon are any indication, Special Forces are indeed in the midst of a golden age.

Special forces soldiers call themselves “the quiet professionals,” but the glamorous image of the hard, square-jawed commando has captured the collective American imagination in films like Zero Dark Thirty and American Sniper, books like No Easy Day, and countless bestselling video games to a far greater extent than the Army and Marine grunts and Air Force and Navy pilots who have carried so much of the burden of the fighting in America’s recent wars.

Their hunt-and-kill missions make big headlines, and showcase the lethal combination of cutting edge military technology with the spartan virtues of America’s elite soldiers—stoic, disciplined, highly trained men who kill the leading villains of jihadist networks without hesitation or mercy. That they fight in a kind of forever war where victory in the traditional sense of the word has lost its moorings only seems to heighten our collective fascination with their exploits.

There’s no mystery as to the origins of SOCOM’s rising influence. It began with the response to the 9/11 attacks, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. These two conflicts created an almost insatiable appetite for SOCOM expertise, and the forces it trains and oversees. More specifically, the golden age of special forces began with the stunning success of the unconventional warfare campaign to decapitate the Taliban and eliminate al Qaeda’s main base of operations in Afghanistan in the fall of 2001.

In the smoldering aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the Bush administration demanded that the ultraconservative Taliban regime then ruling over Afghanistan extradite Osama bin Laden and a number of other leaders of al Qaeda to whom they had granted sanctuary, or face the fury of American retribution. When Taliban leader Mullah Omar refused, Bush, acting largely on the advice of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, eschewed an attack by conventional forces on the grounds that it would take too long to mount, and likely lead to a quagmire guerrilla war along the lines of what the Soviets had endured in Afghanistan in the ’80s.

Instead, the administration opted for a daring and innovative special warfare strategy, combining high-tech U.S. intelligence-gathering technologies, precision air strikes, and a spate of indigenous anti-Taliban militia and warlords as ground forces. CIA covert operatives provided funding for the indigenous fighters, including the Tajik- and Uzbek-dominated Northern Alliance, and Pashtun militia groups in the south under future Afghani President Hamid Karzai. The campaign was organized and planned by the CIA Special Activities Division and the Fifth Special Forces Group, and spearheaded by Green Beret ODA teams, which were attached to the various militia groups to coordinate the ground and air attacks. The operation lasted about two months, and consisted of sequential offensives in the north, south, and eastern regions of the country.

The pattern and tempo of the fighting was remarkably similar in all three areas of operations, as SF teams called in precision air strikes on Taliban defensive positions by fighter-bombers and AC-130 gunships, with devastating effect. Green Berets then joined the local forces in mounting both conventional infantry assaults as well as cavalry charges, typically forcing the Taliban to break and scatter after incurring heavy losses.

Between October 7 and December 7, Taliban strongholds in Mazur-I-Sharif, Kunduz, and finally Kandahar, the spiritual center of the Taliban movement, fell in rapid succession. As the lightning campaign continued apace, Taliban forces fled toward the border with Pakistan, where they went into hiding, not to emerge in significant numbers again in Afghanistan for several years.

At the height of the campaign, in mid-November 2001, Osama bin Laden and several hundred of his fighters left Jalalabad, heading south, where they sought refuge from their pursuers in a 35-square mile cave complex near the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, high in the White Mountains. It was called Tora Bora.

Here the notorious al Qaeda chief and his supporters came under attack by an unsavory league of warlords dubbed the Eastern Alliance by their American and British SOF coordinators. As they closed in on the highest of the high-value targets, American special operators requested the deployment of conventional U.S. ground forces to cordon off the porous Afghanistan—Pakistan border area. The Bush administration, determined to maintain a light U.S. footprint on the ground, denied the request. It was one of the first unfortunate decisions in an administration that would make a great many of them in the GWT.

It’s widely believed Osama bin Laden and a coterie of his bodyguards were able to bribe their way out of the Tora Bora complex in mid-December, fleeing into the rugged tribal region of Pakistan, and beyond the reach of the American-led coalition forces.

Nonetheless, SOCOM, with the assistance of the CIA, had orchestrated one of the most successful unconventional warfare campaigns in military history. Unfortunately, that effort proved to be but the first chapter in a protracted insurgency war for which neither the Bush administration nor the Pentagon’s chief strategists had prepared.

Then, in a monumental display of strategic ineptitude at the highest levels, it happened all over again in Iraq. The spring 2003 conventional invasion of Iraq led to the rapid collapse of the Baathist regime of Saddam Hussein. Special Forces planned and executed another bravado unconventional warfare campaign in that conflict—this time leading Kurdish Peshmerga forces to a series of operational triumphs in northern Iraq and tying up at least a half dozen Iraqi regular divisions in the process.

But Saddam’s defeat merely ushered in yet another protracted insurgency—this one on a far greater scale of complexity than that in Afghanistan—and yet again, there was no coherent counterinsurgency strategy in place on paper, let alone in the field. Nor had America’s deployed conventional forces been trained to fight in a counterinsurgency environment in anything more than the most cursory fashion.

Into the breach stepped SOCOM, the military command created by an act of Congress in 1987 to “provide the United States with immediate and primary capability to respond to terrorism,” to conduct counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare campaigns, and to serve “as the military mainstay… for the purposes of nation-building and the training of friendly [indigenous] forces …” In both Afghanistan and Iraq, the absence of viable friendly government institutions, especially police and military forces, tested SOCOM’s indirect action missions—organizing and training nascent Afghan and Iraqi forces in counterinsurgency tactics, training local police and village defense forces, and providing civic action battalions to develop roads, schools, and medical facilities—to the breaking point. SOF psychological operations teams also took up much of the burden of developing propaganda campaigns to buttress support of the local population for the fledgling national governments, and to sever the connective tissue between the people and the myriad sectarian insurgencies that challenged the new national administrations in both nations at every turn.

And so the rapid increase in size and influence of SOCOM on the American military-national security apparatus continued apace in the mid- and late-2000’s.

As U.S. conventional forces struggled to quell the insurgencies in both countries, for the first time in U.S. military history, Special Forces officers were placed in charge of conventional combat units in order to accomplish hybrid missions, combining direct action raids against high value targets with conventional infantry assaults supported by artillery and air power against insurgent enclaves.

To drive Muqtada al Sadr and his Shiite militia out of Najaf, Iraq, in 2004, U.S. commanders employed a sophisticated amalgam of SEAL team raids on militia leaders’ strongholds, Green Beret-led indigenous militia strike forces, and conventional light infantry and tank forces. After SOF units conducted special reconnaissance missions and surgical raids deep in enemy held territory, conventional forces swept in to clear away large pockets of insurgents in the same area of operations.

In the bitter trials of hundreds of joint operations across Iraq and Afghanistan, much of the longstanding mistrust and misunderstanding between conventional and special operations forces—a mistrust that extended back to World War II and Vietnam—was shorn away by shared sacrifice and a growing recognition that operational success in irregular wars against both terrorist networks and sectarian insurgencies was crucially dependent on SOF-conventional unit synergy.

Army General Ray Odierno, who served as top commander in Iraq from 2008 to 2010, played a key role in integrating conventional and special operations missions there. As Chief of Staff of the Army from 2011 to 2015, Odierno worked hard to create a new set of formal relationships between SOCOM and the regular army. Among his initiatives was a program to train conventional units alongside SOF units, and deploy them together overseas. Linda Robinson, a highly respected RAND Corporation expert on Special Forces, told The Daily Beast in an email that the Army and the other services have at long last come to a “widespread agreement that SOF has a significantly larger role” to play in planning for future conflicts than it did in the pre-9/11 environment.

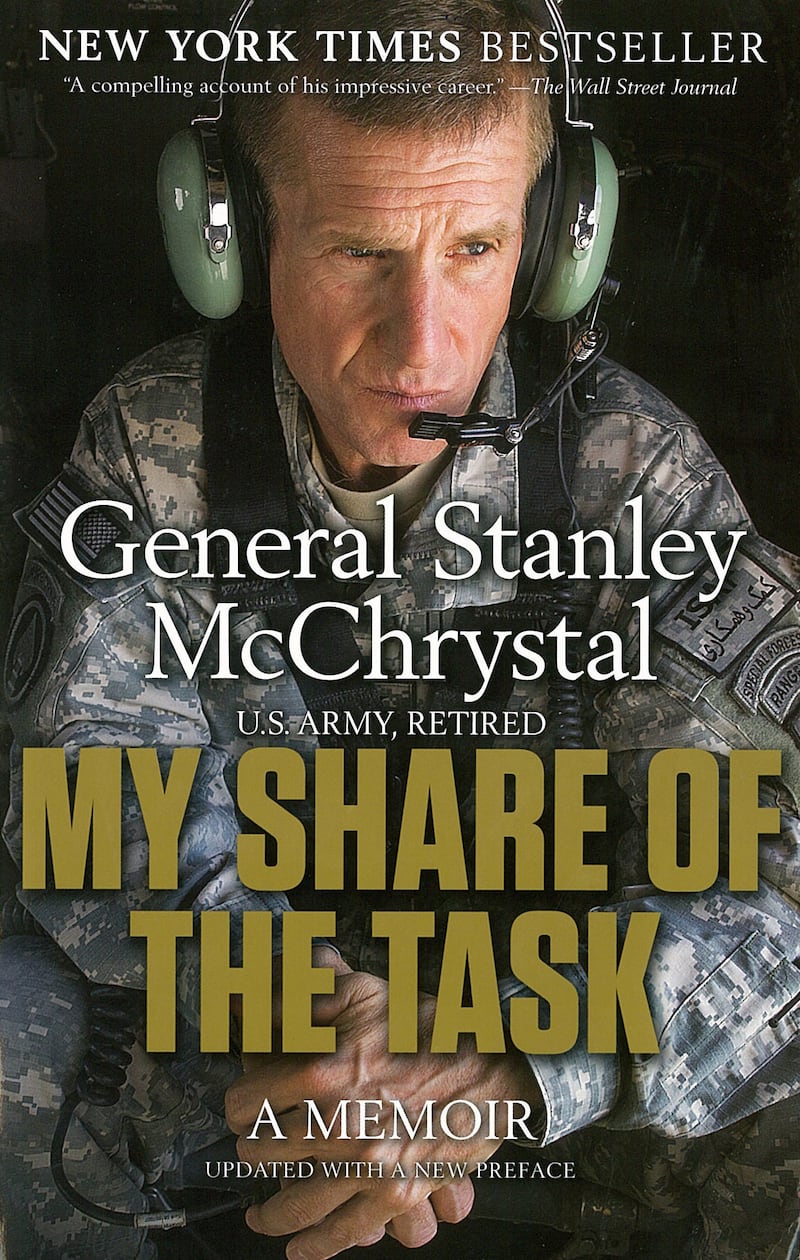

It was during the early years of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars that a hard-charging, intense, Special Forces general named Stanley McChrystal increased the size and lethal capabilities of the clandestine task force responsible for gathering intelligence on terrorist networks, and taking down high-value targets. As head of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), the secrecy-shrouded sub-command that controls (unofficially) SEAL Team 6, the Delta Force, and the Air Force’s 24th Special Tactics Squadron, McChrystal worked like a man possessed to break down the walls between the vast array of U.S. and allied intelligence-gathering organizations, and to make seamless connections between JSOC and top conventional commands in Afghanistan and Iraq. With the help of Col. Mike Flynn, McChrystal developed an innovative “nodal analysis” technique for rapidly processing vast amounts of intelligence on enemy networks and targets.

McChrystal’s mantra, as he put it in his book, My Share of the Task, was, “It takes a network to defeat a network.” By the time JSOC’s new system was up and running, everyone involved in target acquisition, mission planning, execution, and follow-up had unimpeded access to real-time intelligence. According to military analysts Charles Faint and Michael Harris, the new JSOC system for targeting terrorists—“find, fix, finish, exploit, analyze, and disseminate”—F3EAD, or “feed” for short—allows SOF to anticipate and prevent enemy operations, identify, locate, and target enemy forces, and to perform rapid analysis of captured enemy personnel and material” that often leads to a fresh set of targets and raids.

Thus, F3EAD established a powerful, symbiotic relationship between intelligence-gathering and operations unprecedented in the long history of anti-terrorist operations. Since the system has been implemented, JSOC has been able to plan and execute an extraordinary number of successful commando raids, drone attacks, and precision air strikes. The first high-visibility success of F3EAD was the capture of Saddam Hussein in December 2003. At the height of the surge in Iraq in 2007, a year or so after a JSOC task force had killed Abu Musab Zarqawi, leader of al Qaeda in Iraq, the precursor organization of ISIS—American commando teams were reportedly conducting as many as 14 raids a night. According to Linda Robinson, “successive raids were made possible by intelligence scooped up during the previous one and then rapidly processed.”

The raids currently at the forefront of the Obama administration’s strategy to defeat ISIS in Iraq and Syria build on the success of JSOC’s direct action operations in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Will they succeed against ISIS? The best answer as of this writing may be, “yes, and no.” The worry, say many military and foreign policy analysts, is that there is an inclination on the part of some members of our senior military leadership, policy makers, and the American public alike to mistake the raids’ dramatic tactical and operational success for strategic progress. That, said David Tucker, former longtime professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, and co-author with Christopher Lamb of an acclaimed book, United States Special Operations Forces, is a mistake. Unless the raids are part of a well-integrated politico-military strategy involving indigenous forces, said Tucker in an interview with The Daily Beast, there are strict limits to what these raids alone can accomplish against an organization as complex and resilient as ISIS.

There seems to be a strong consensus inside the special forces community, and among professional analysts of that tribe that, given the Obama administration’s commitment to a national security strategy that pivots on empowering our allies to defend and govern themselves, SOCOM’s most urgent challenge over the next few years is to step up its “indirect action” game, much as it built up its capabilities in direct action operations over the past decade. What William McRaven said in March 2011, just two months before Osama bin Laden was killed in the most celebrated commando raid in American history still holds true today: “The direct approach alone is not the solution to the challenges our nation faces today, as it ultimately only buys time and space for the indirect approach.”

What makes SOF’s indirect missions so challenging is that all of them—forging partnerships with foreign militaries as trainers and advisers; developing unconventional warfare campaigns with those forces, equipping and training militias and insurgencies in failing nation states like Syria, working in rural areas directly with tribal leaders and the local populace to develop village defense forces, and providing medical and economic assistance to host governments—engage operators in activities where political and military actions intersect. The indirect approach to warfare is, in essence, a political approach, in that organizational and motivational work takes precedence over tactical operations.

As such, the challenges U.S. advisers encounter in indirect missions don’t lend themselves to cookie-cutter, “by the book” protocols and technological solutions that are the forte of hierarchical institutions like the conventional U.S. military services. They call on soldiers, both special forces troops who spearhead such partnerships and the conventional forces and State Department advisory teams who flesh out and build on their work, to think of conflict in its broadest political context. The indirect approach requires flexibility, creativity, and a firm grounding in local languages and cultures that comes only with considerable academic study, coupled with extensive “on the ground” experience.

In short, indirect missions demand longstanding commitments and patience, neither of which have been the strong suit of our political leaders, or an American military culture that strongly inclines toward fast, technologically-driven solutions to problems. As John Nagl, a retired army officer, counterinsurgency expert, and leading advocate of establishing a permanent adviser corps in the U.S. Army puts it, “The United States military’s ability in battle is unmatched, but we have a spotty history in terms of helping allies fight for themselves.”

The much-publicized recent collapse of a $500 million Green Beret program to train Syrian rebels reminds us of the daunting challenges these missions pose to even the most dedicated and knowledgeable trainers in the U.S. military. It’s sobering to recall that the shining success of the unconventional warfare campaign against the Taliban in Afghanistan led by the Green Berets occurred 15 years ago. Since that time, the performance of SOF-trained and led indigenous forces in both Afghanistan and Iraq has been decidedly mixed.

Perhaps the most important question right now for the Obama administration’s nascent military strategy against ISIS concerns the effectiveness of the special forces advisers tasked with melding our coalition partners—the Peshmerga, the Free Syrian Army, the Iraqi Army, various Shia militia groups—into a cohesive, resilient ground army that can take the fight to ISIS at the battalion and regimental level, and win. Recent reports from the field suggest there are neither enough SOF advisers, nor sufficient allocations of weapons and funding to our partners, to meet the challenge.

And it seems clear that in the long run, SOCOM and the American military in general will need to put more creativity and resources into training and supporting the warrior-diplomat soldiers who spearhead America’s indirect action campaigns if they expect the kind of concrete success in ground operations with our partners that we have seen with JSOC’s commando raids.