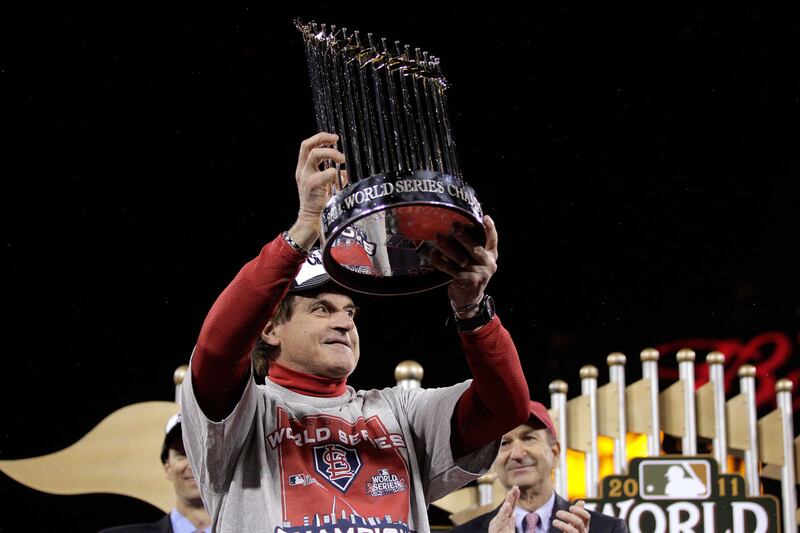

Whether you loved Tony La Russa, as many millions of fans did, or hated him, as far too many millions of fans did, the verdict on him is simple. In the aftermath of Monday’s surprising announcement, three days after his St. Louis Cardinals won the World Series, that he was retiring after a 33-year managerial career, we might as well get the boilerplate of his legacy out of the way so there is no confusion:

Over the past half-century of Major League Baseball, the 67-year-old has been the game’s best manager, best innovator, best thinker, and best strategist. There is no argument, at least to those who appreciate baseball. He also makes the current rage, Billy Beane of Moneyball book and film fame and the general manager of the Oakland Athletics, look like the general manager of a T-ball team in Toledo in terms of accomplishment, as opposed to hype and exaggeration.

It also should be pointed out right off the top that I wrote a book about the managerial strategy of La Russa six years ago called Three Nights in August. The La Russa irrationalists will immediately go into temper-tantrum mode and claim that I am lauding La Russa for the sole purpose of selling more copies of the book. If the book does sell more copies, and God I hope it does, it will be because of the remarkable performance of the St. Louis Cardinals in the playoffs that ended Friday with perhaps the most improbable World Series win in history over the Texas Rangers. It won’t be because of this column.

I do not agree with everything that La Russa has done on baseball or off baseball.

Hiring Mark McGwire as the team’s hitting coach, after McGwire lied to the American public about his performance-enhancing drug use for more than a decade and gave utterly ridiculous testimony before Congress, was an act of La Russian stubbornness: over and over he publicly insisted that McGwire’s bursting-at-the-seams body, when he broke the single season record for home runs with the Cardinals in 1998 with La Russa at the helm, was the result of working out.

We have had other differences and once stopped speaking. But I find him one of the most remarkable men I have ever met, as well as one of the most complex and most misunderstood—smart, relentless, kind, humble, funny, and in terms of baseball, more risky and daring than perhaps any manager in history.

The game of baseball is largely moribund. Change, real change that has real results as opposed to change that sounds sexy and has no real results (see Michael Lewis’s Moneyball, as notable for what he omitted as for what he wrote, not to mention Billy Beane’s perfect record in the World Series because he has never been in the World Series) comes in painfully slow doses. But La Russa saw the game differently. His attitude has always been that if you think about something hard enough, you come up with a solution. And that was the way La Russa managed, thinking about the game 24 hours a day because he lived a self-imposed life of no distraction.

Sometimes the strategy had mixed results, like deciding for several seasons to bat the pitcher eighth. But the overwhelming majority of the time the strategy worked, not just from one game to another but in effecting lasting change. It was La Russa, in concert with his genius pitching coach Dave Duncan, who defined the use of the ninth-inning closer when they were with the Oakland A’s and wanted to utilize starter-turned-reliever Dennis Eckersley in as many games as possible. It was La Russa who used computer analysis as far back as the early 1980s when he was managing his first team, the Chicago White Sox. It was La Russa who paid obsessive attention to how certain batters did against pitchers and vice versa and therefore adjusted his strategy accordingly. And it was La Russa who elevated the role of situational relief pitching into a whole new dimension in this year’s playoffs by calling for his bullpen a record 75 times, and winning the World Series despite no starter going more than five innings in the National League Championship Series against the Milwaukee Brewers.

There are those who hated La Russa because they felt he acted as if he had invented the game of baseball and was arrogant. They loved to derisively call him the “genius,” as if it were an appellation that La Russa had given himself. He hated the tag and had it ordained upon him by Sports Illustrated when it ran an excerpt of George Will’s Men at Work that featured La Russa, among several others.

The irony is that La Russa was the furthest thing from arrogant. Fiercely loyal to his team whatever the circumstance, yes. A man who suffered fools gladly, no. Suspicious of a media he felt was always looking for dirt, yes. Sometimes far too intense for his own good, yes. So manically dedicated to his craft that he did not live with his family in Northern California during the season when he was with the Cardinals for 16 seasons, but in a hotel suite. Yes.

But he did not manage out of arrogance or thinking he knew more about the game than anyone else. He managed out of fear, the fear of losing a game because he had missed something he should not have missed. And when you sat with La Russa after a game and he began to talk baseball, it was never himself he focused on but the baseball men he worshipped and said over and over he was lucky enough to have been around when they were in their prime—Chicago White Sox owner Bill Veeck, hitting coach Charlie Lau, managers Paul Richards and Sparky Anderson and Billy Martin and Bob Lemon.

The passing of the era of Tony La Russa is not just the passing of his own era in which he finishes as the third-winningest manager in baseball history, with three World Series rings. It is also the passing of a certain era of baseball, the last of a certain kind. He started managing in 1979 at the age of 32. After each home game, owner Veeck would assemble his favorite baseball minds in the Bard’s Room of old Comiskey Park, and during wild arguments over the hit-and-run and the bunt and the pitchout, the cigarettes and booze flowed until the wee hours of the morning.

La Russa loved the lore of baseball. He was a romantic at heart, but the best thing about him is that he changed with the game. He still looked for ways to turn baseball on its head with positive results. He still managed every game as if it were the first game he ever managed so he would not get lazy, exhausting to contemplate, given he managed 5,097 games. He also had great respect for the work of the famed sabermetrician Bill James. Just as he also realized that no matter how many numbers you pour into a computer, there will never be a way to quantify the intangibles of heart and chemistry and desire that define the success or failure of all of us.

I for one hope the naysayers do come around. Because in baseball, in any sport, a person like Tony La Russa only comes around once in a lifetime.