“It’s an extension of the fairy tales we read as kids. Or the monster stories or stories about witches and sorcerers. You get a little older, and you can’t bother with fairy tales and monster stories anymore, but I don’t think you ever outgrow your love for things that are fantastic, that are bigger than you are—the giants or the creatures from other planets or people with superpowers who can do things you can’t.” – Stan Lee

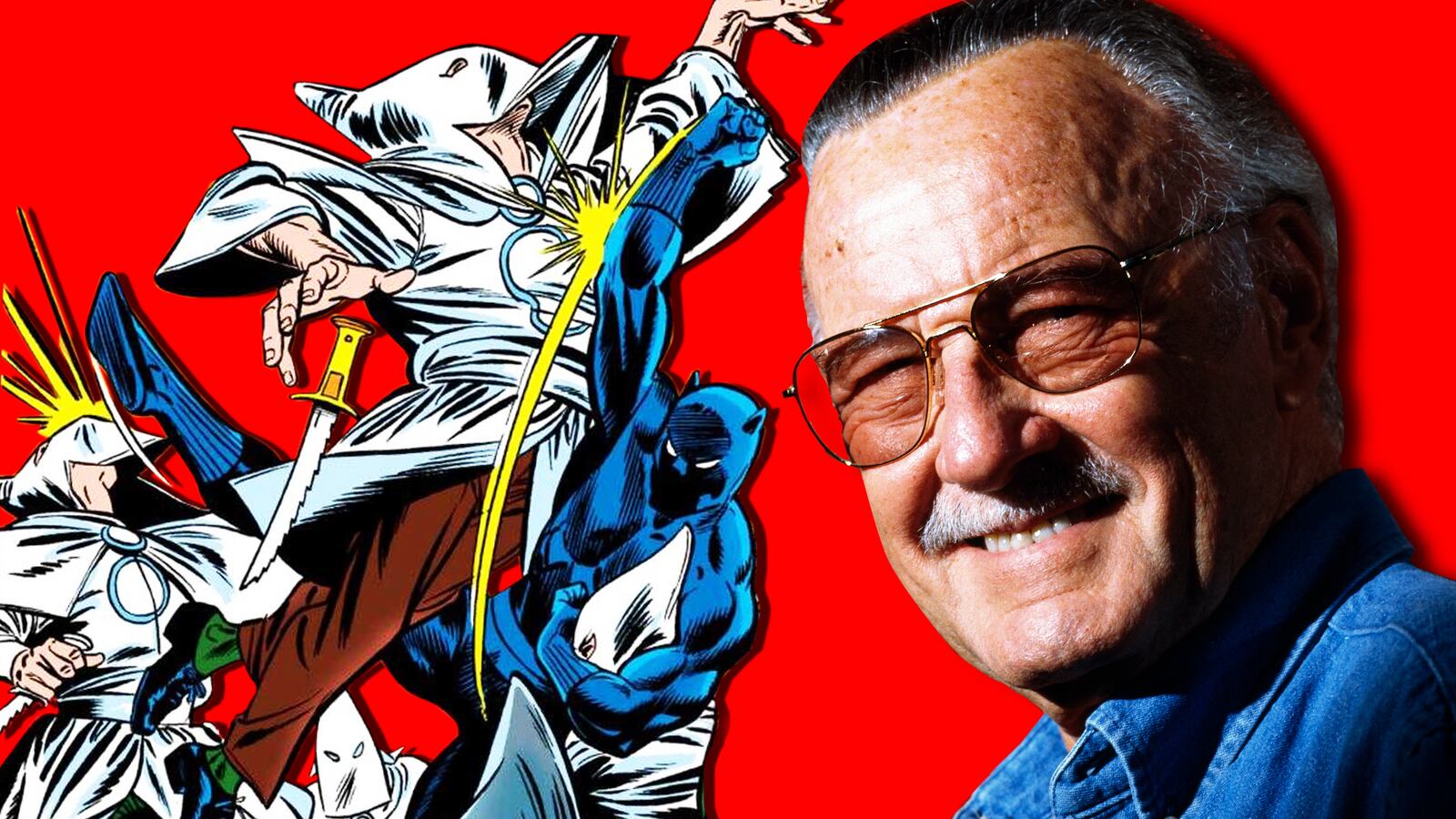

Stan Lee has passed away at age 95, and the famed “Smilin’ Stan” that the world knows as the face of Marvel Comics leaves behind a towering legacy. Lee created characters and told stories that reflected the struggle in American society between the idealized way we view ourselves and the harsh ugliness in our culture that is impossible to ignore. Born Stanley Martin Lieber in New York City, the beloved comics legend co-created iconic superheroes like Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, The Incredible Hulk, Daredevil, the Avengers, the X-Men and Black Panther in the 1960s, helping to establish Marvel Comics as the foremost rival to longstanding D.C. Comics.

Lee’s characters and stories reflected the pathos in ‘60s culture—giving voice to adolescent angst via Spider-Man just as the youth culture boom of the decade was beginning to take hold; addressing then-current anxieties about space exploration via the Fantastic Four; using the Hulk as a metaphor for repression and government shadiness; and the X-Men functioned as a symbol for marginalized citizens’ fight for their right to exist. Alongside fellow luminaries such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, Lee set Marvel apart not only by placing its super-powered protagonists in the middle of real-world troubles but beyond that, by giving voice to those issues. To fully appreciate what that means, one has to understand the cultural landscape when Lee rose through the ranks at Marvel.

In the mid-1950s, watchdog groups derided comic books as a scourge—a corrupting element in youth culture that promoted the occult, violence and deviancy. Lee and Kirby debuted Black Panther in 1966 in the pages of Fantastic Four. Marvel’s first black hero was prince of a fictional African nation called Wakanda and, despite some unfortunate characterizations (The Thing refers to the country as “Tarzan land” in an early panel), the presentation of a black superhero from Africa with supreme intellect and advanced technology was groundbreaking and indicative of what made Lee’s tenure special.

“Marvel has always been and always will be a reflection of the world right outside our window,” Lee said in a popular 2017 video. “That world may change and evolve, but the one thing that will never change is the way we tell our stories of heroism.

“Those stories have room for everyone, regardless of their race, gender or color of their skin. The only things we don’t have room for are hatred, intolerance and bigotry.”

Lee has talked about the popular X-Men as a metaphor for black Americans’ struggle for civil rights. In Marvel canon, the X-Men are part of a human subspecies called mutants, born with superhuman abilities and hated by much of humanity for what they are. It has been widely accepted that Charles Xavier, the X-Men’s idealistic founder, was loosely based on Martin Luther King, Jr.; while the team’s most famous foe, Magneto, was drawn from Malcolm X. Xavier believes that humans and mutants can peacefully coexist; Magneto believes mutants must overthrow humans before they are decimated by their hateful oppressors.

“I did not think of Magneto as a bad guy,” Lee once said. “He was just trying to strike back at the people who were so bigoted and racist. He was trying to defend mutants, and because society was not treating them fairly, he decided to teach society a lesson. He was a danger of course, but I never thought of him as a villain.”

Lee understood how comic books reflected and affected those who read them. He also understood that great storytelling connected with the times. It should be noted that the dynamic between Xavier and Magneto, in particular, evolved over time, and in the hands of various other writers like Chris Claremont, the parallels with King and X became more apparent. Lee was uneasy about Black Panther being associated with the revolutionary party of the same name (so much so that the character was almost rechristened “Black Leopard”) and Magneto’s background as a Holocaust survivor was another Claremont development. As was the case with many iconic, long-running comics heroes, Lee’s original vision was expanded upon, but the history of collaboration has often led to commentary about how much credit should go to Marvel’s most iconic creator.

Lee loved the fans and loved the spotlight, to the point where there was criticism that he was a glory hound. His penchant for self-promotion spawned criticism from former colleagues and observers, especially those who felt he’d overshadowed and taken credit from collaborators like Jack Kirby and Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko. Kirby, whose artwork came to define the Fantastic Four and X-Men, was a freelancer, as opposed to a Marvel employee like Lee.

“There was never a time when it just said ‘by Stan Lee,’” Lee told Playboy in 2015. “It was always ‘by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’ or ‘by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby.’ I made sure their names were always as big as mine. As far as what they were paid, I had nothing to do with that. They were hired as freelance artists, and they worked as freelance artists. At some point they apparently felt they should be getting more money. Fine, it was up to them to talk to the publisher. It had nothing to do with me. I would have liked to have gotten more money, too.”

Regardless of ongoing controversy surrounding the contributions of Kirby and others, Lee should be remembered for being an agent of change in his medium. A 1968 post from Lee’s mail column has been making the rounds in the wake of his death. In it, Lee makes plain his stance on racism.

“Let’s lay it right on the line. Bigotry and racism are among the deadliest social ills plaguing the world today. But, unlike a team of costumed super-villains, they can’t be halted with a punch in the snoot, or a zap from a ray gun. The only way to destroy them is to expose them—to reveal them for the insidious evils they really are. The bigot is an unreasoning hater—one who hates blindly, fanatically, indiscriminately. If his hang-up is black men, he hates ALL black men. If a redhead once offended him, he hates ALL redheads. If some foreigner beat him to a job, he’s down on ALL foreigners. He hates people he’s never seen—people he’s never known—with equal intensity—with equal venom.

“Now, we’re not trying to say it’s unreasonable for one human being to bug another. But, although anyone has the right to dislike another individual, it’s totally irrational, patently insane to condemn an entire race—to despise an entire nation—to vilify an entire religion. Sooner or later, we must learn to judge each other on our own merits. Sooner or later, if man is ever to be worthy of his destiny, we must fill our hearts with tolerance. For then, and only then, will we be truly worthy of the concept that man was created in the image of God—a God who calls us ALL—His children.”

Stan Lee’s creative voice helped reshape the role of comics in American society and helped affect how American society saw comics. In doing so, Lee helped challenge his readers and his peers. His characters live now as part of the fabric of our culture—in blockbuster movies, acclaimed TV shows, video games and a host of other media. Generations of comic-book lovers saw themselves in those characters, and that was what he’d wanted all along. As some quarters of America tell themselves that politics have no place in pop art, the proof in Stan Lee’s history reminds us that the message has always been a part of the medium. Those who believe otherwise maybe have to consider that they aren’t the “good guy” in the story. After all—you can’t be a hero if you don’t stand for anything.