The U.S. military is quietly developing a stealthy “fifth-generation” drone warplane with potentially cutting-edge combat capabilities. But the drone isn’t technically a frontline fighter. It’s a target—in essence, a high-tech clay pigeon that Pentagon war-game organizers would launch into the air for fighter pilots to hunt down and destroy for training purposes. Largely unnnoticed by the mainstream media, the Air Force has been tinkering with new software that, with the flip of a switch, transforms target drones into robotic “wingmen” for manned F-22 and F-35 stealth fighters.

Combine the new software with the radar-evading target drone and you’ve got the world’s first armed robotic jet fighter—and a big advancement compared to today’s propeller-driven surveillance drones.

“If we do it right, a custom-built stealthy target aircraft is going to have a performance envelope that’s pretty close to an actual stealth fighter,” Dan Ward, a retired Air Force officer and author of The Simplicity Cycle: A Field Guide to Making Things Better Without Making Them Worse, told The Daily Beast.

“The target drone will lack many of the bells and whistles of a full-up stealth fighter, but that’s more feature than bug,” Ward added. “The drone is designed to only do the core essential functions, and most of the time, that’s what we really need anyway.”

The Air Force began work on the Fifth-Generation Aerial Target, or 5GAT, way back in 2006. At the time, the military mostly used Vietnam War-vintage F-4 fighters as targets, fitting the old F-4s with remote controls, adding a “Q” to their designation to indicate their target status and then sending them zooming over training ranges for the flying branch’s F-15s, F-16s, and F-22s to shoot down.

The Air Force ran out of QF-4s in 2015 and began adding the remote controls to decommissioned F-16s, instead. Both the QF-4s and the QF-16s—“third-generation” and “fourth-generation” warplanes, respectively—are supersonic and at least reasonably maneuverable.

But there’s one thing the old drones are not—stealthy. Both jet types lack the carefully-calculated angles that help stealth fighters such as the Air Force’s F-22s and F-35s to scatter electromagnetic energy and keep them off of radar scopes.

With both Russia and China developing radar-evading warplanes of their own, the Air Force decided it needed a new target drone that could help American fighter pilots and missile crews learn how to find and destroy enemy stealth planes.

“The target drone’s intended uses are to test air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles, and to ensure that modern tracking systems are capable of identifying and targeting fifth-generation fighters,” Dennis Carter, Patrick Burris, and Steven Brandt—three of the 5GAT’s lead designers—wrote in a 2011 academic paper (PDF).

“5GAT will represent stressing characteristics of fifth-generation threat aircraft that cannot be met by the QF-4 or QF-16,” Maj. Roger Cabiness, a spokesman for the Pentagon’s Director of Operational Testing and Evaluation, or DOT&E, which oversees the target-drone project, told The Daily Beast.

Because it’s a mere target at the moment and—by aerospace standards—unglamorous, the 5GAT largely eluded the attentions of the U.S. defense industry.

It’s an industry that, for obvious reasons, has a bad habit of producing the extraordinarily complex and expensive warplanes. After all, complex designs require lengthy and costly research and development that the government—and by extension, the public—underwrites. And expensive designs maximize corporate profits.

Instead of contracting out the 5GAT to industry, the Air Force organized a mostly internal contest between four teams to design the 5GAT. Brandt, a professor at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, led a team composed mostly of Air Force cadets in their early 20s. The whole competitive design effort set the government back just $11 million.

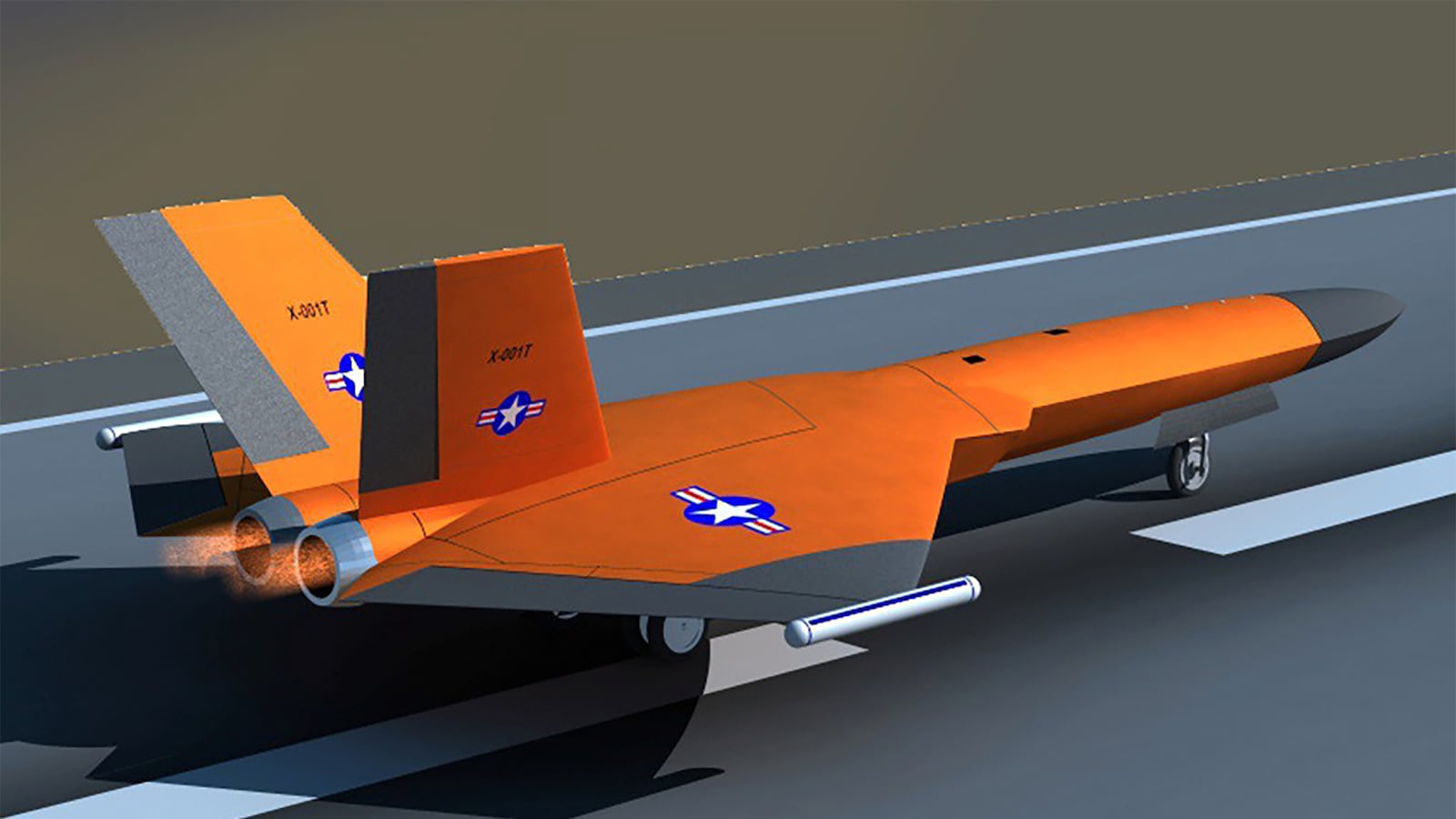

The cadets’ winning design, which is 41 feet long and weighs just three tons minus fuel, emphasizes arguably the most important qualities of a stealth warplane—lightness and the angles of its wings—and strips out other features that might add performance but aren’t necessarily worth the extra cost. “It’s a case of the 80 percent solution outperforming an over-engineered 110 percent solution—and doing so for one 10th of the price,” Ward commented. What’s more, the 5GAT is stealthier than an F-16 is—although exactly how stealthy is classified—and much less expensive than is any fighter the Air Force is currently buying. Modifying an F-16 into a QF-16 costs the government around $1.5 million. Compare that to the price tag on a single Lockheed Martin-made F-35 stealth fighter: more than $100 million.

5GAT blueprints in hand, the Pentagon is now working on an actual flyable prototype. Finishing this prototype will cost $27 million, the Defense Department’s main testing agency reported in January 2016. Cabiness said the prototype should be ready to fly by 2019 or 2020.

“The prototyping effort will provide cost-informed, alternative design and manufacturing approaches for future air vehicle acquisition programs,” DOT&E explained in its most recent annual report. “These data can also be used to assist with future weapon system development decisions.”

That last comment is important. Translated into plain English, it means the 5GAT could, in the future, inspire robotic planes that are more than just target drones. The 5GAT could even itself evolve into a frontline weapon. That’s because, in 2015, the Air Force’s research branch began developing new computer algorithms that could add autonomous combat capability to the military’s target drones.

The so-called Loyal Wingman program takes those clay-pigeon QF-16s and swaps out a few black boxes—“line replaceable units,” or LRUs, is their technical designation. Voila, you’ve added all the code the robot plane needs to reverse roles, and evolve from the hunted to the hunter. The first Loyal Wingman drone is scheduled for flight tests in 2018.

“You take an F-16 and make it totally unmanned,” Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work told an audience in Washington, D.C., in March. “The F-16 is a fourth-generation fighter, and pair it with an F-35, a fifth-generation battle network node, and have those two operating together.”

The armed former-targets could accompany F-35s and other manned fighters into combat, flying ahead to scout for the enemy or carrying extra missiles to blast targets that the stealth-fighter pilots pick out. The one problem with the concept is that an F-35 is stealthy—an F-16 isn’t. An accompanying F-16 (even the armed target drone version) could betray an F-35’s location.

But the robotic F-16 isn’t the only eligible “Loyal Wingman.” LRUs are, by design, compatible with a wide range of plane models. Install in a 5GAT the same LRUs and you’ve got a drone wingman that’s potentially as stealthy as the F-22 or F-35 it’s flying alongside of.

Asked whether 5GAT could become a frontline combat drone under the Loyal Wingman program, Cabiness was evasive. “Since Loyal Wingman is conceptual at this point in time, it would be premature to state that 5GAT could fit the Loyal Wingman mission,” he told The Daily Beast.

But Peter W. Singer, an analyst at the Washington, D.C.-based New America Foundation and author of the recent technothriller Ghost Fleet—whose plot involves robotic wingmen fighting alongside manned jets—told The Daily Beast that a war-ready 5GAT makes sense.

“The new tech open all sorts of new possibilities,” Singer said. “Can the drone operate like a wingman, or does it get used more like a swarm? Does the human pilot manage it or team with it? Do you even deliberately use the target drone in battle the way it was intended, deliberately sacrificing it to make the enemy use up their missiles or reveal themselves?

“The possibilities are amazing,” Singer added, “if we allow ourselves to take advantage of them.” And thanks to the simple, cheap, but potentially very effective stealth target drone, and the new computer code that could teach it fighting skills, the Air Force has the opportunity to try out a new kind of air combat. Fast, maneuverable, stealthy, drone air combat.