Steve Ditko did not like publicity, or awards, or being asked about his career. He was famously temperamental and sent many reporters—including me—packing.

Ditko, the artist who gave the world Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, and dozens of other characters he created or co-created for Marvel and DC Comics, has died at the age of 90, the NYPD confirmed to The Hollywood Reporter. He was found in his apartment on June 29. Authorities believe he had been dead for about two days.

For this beloved artist, the focus was entirely on his work, and he wanted other people’s focus there, too. “I never talk about myself,” he said when his own editors asked for a promotional interview after he’d created a new character, The Creeper, for DC Comics in 1974. “My work is me. I do my best, and if I like it, I hope somebody else likes it too.”

Pretty much everybody else did like it. There is a peculiar grammar to comics, a way that one panel suggests the next panel, that is ephemeral and hard to learn; some people intuitively understand it and reading their comics is like watching actual movement. Ditko is their patron saint. “Ditko shared with… a few others that hidden hand of tone and style and clarity that just punched through your brain as a young kid, every panel a window into a worldview as formed and grand and sad as yours was new,” comics journalist Tom Spurgeon observed on Twitter in light of Ditko’s passing.

The great artist’s intuition is surely due in part to the way Ditko was asked to work on his most famous creation, Spider-Man, dreamed up by Marvel Comics writer-editor Stan Lee, who supplied Ditko with plots and went back and filled in the dialogue after Ditko was done drawing.

Eventually, Ditko’s storytelling acumen so impressed Lee that he stopped telling Ditko what to draw at all—he just supplied captions, heroic one-liners and villainous speeches. “It was like doing a crossword puzzle—[the comic] was something I’d never seen before and I didn’t know what to expect,” Lee told BBC interviewer Jonathan Ross in the latter’s 2007 documentary about Ditko.

Ditko and Lee’s falling-out was the stuff of their own hero-villain archrivalries, with Ditko feeling keenly that Lee, with his expansive public persona and easy schmoozing, was hogging all the credit for the introverted Ditko’s hard work. (He wasn’t the only artist to feel this way; Jack Kirby, who created the lion’s share of the Marvel Universe in books where Lee provided dialogue and sometimes plots, portrayed his old colleague as a sleazy huckster named Funky Flashman in a comic he drew when he left Marvel for chief competitor DC.) At one point, Ditko extracted a letter from Lee giving the artist credit as co-creator—but Lee wrote that he had “always considered” Ditko an equal partner; Ditko, upset over the use of the word “consider,” rejected the olive branch and Lee dropped him, according to Lee. “There’s no pleasing Steve,” Lee says in Blake Bell’s Ditko biography, Strange and Stranger. Or rather, only one thing seemed to please Steve, namely comics.

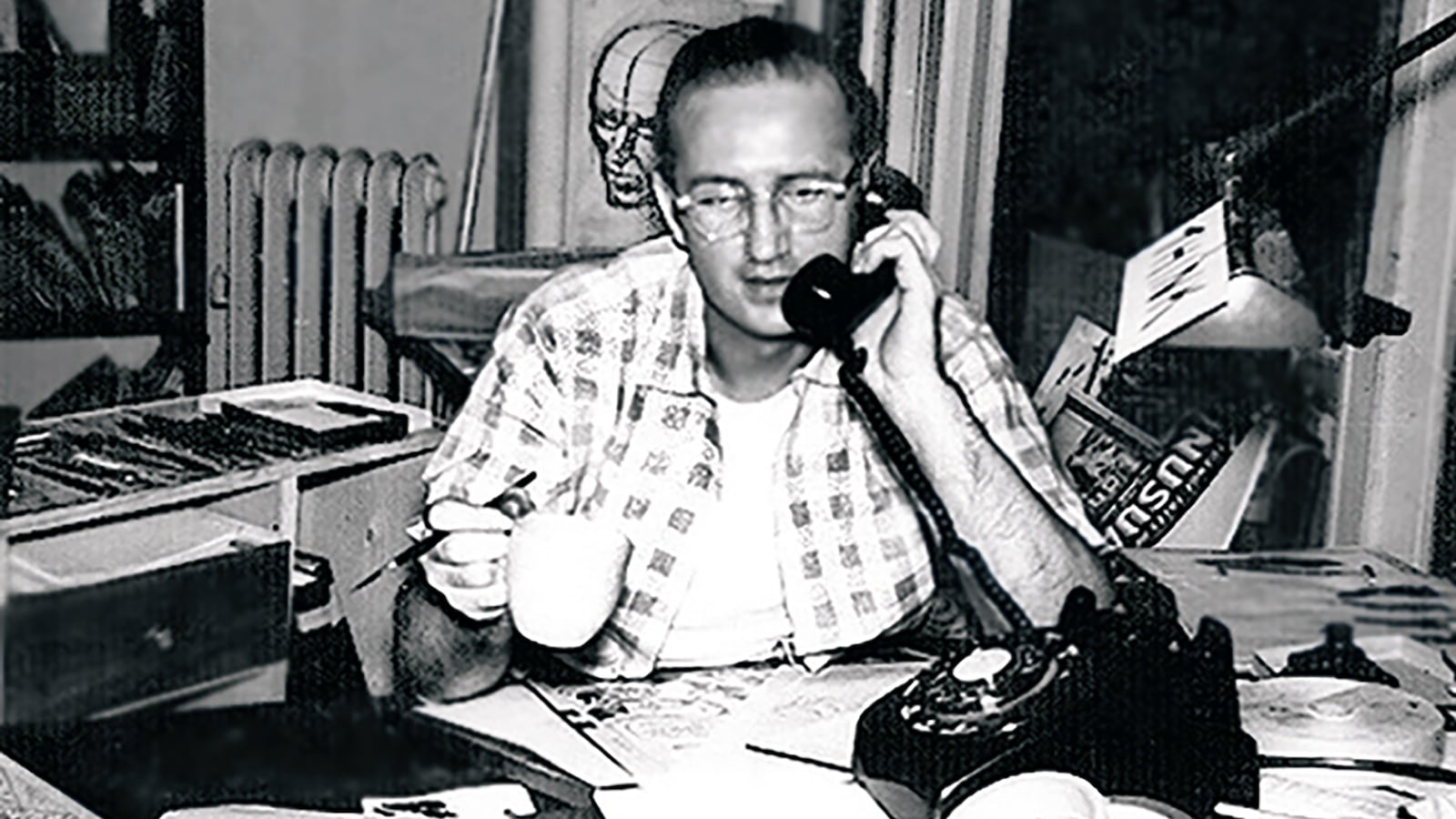

Steve Ditko HS Yearbook

AlamyBorn in 1927 to a working-class Johnstonwn, Pennsylvania, family that, like most, struggled financially through the Great Depression, Ditko learned to love comics from his father, whose annual Christmas present from his four children was all 52 of the year’s Prince Valiant Sunday strips by Hal Foster, carefully clipped from the local Hearst paper and bound in cloth. His artistic influences included Will Eisner, creator of hero detective The Spirit, which Ditko read in the newspaper, as well. Unlike many cartoonists of his era, he was not a failed commercial artist. He really wanted to draw comics.

And draw them he did, right up until his death. Ditko was monstrously prolific: A Kickstarter campaign for a new book, written with Robin Snyder, his business partner of the past three decades, ended a few days after his death. And there’s loads of their-money-is-green work that Ditko drew decades after revolutionizing the medium; fans checking bylines in the back-issue bin may be surprised to see Ditko’s name on copies of cut-rate productions like Tiny Toon Adventures and Phantom 2040.

But unilke the slick corporate licenses he contributed to, Ditko’s own creations were always eccentric and memorable—the giggling, yellow-skinned, green-haired Creeper is downright normal compared to Mr. A, the Ayn Rand-loving artist’s objectivist mouthpiece. They often had an improbable staying power: One of his strangest characters, Squirrel Girl, is now heroine of one of Marvel’s best-regarded series, a kid-friendly humor book. Another of Ditko’s odder ideas, a faceless vigilante called The Question, inspired Rorschach, the antihero of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ magnum opus, Watchmen.

Encounters with Ditko vary wildly: Abe Riesman at New York Magazine politely tried to set up an interview by phone and then staked out Ditko's office; he didn’t even get a handshake. Neil Gaiman had a 20-minute conversation and left the same studio with a stack of comics—but told the BBC he couldn’t say anything about the contents of the apparently delightful conversation.

Ditko’s address was easy to find: 1650 Broadway, suite 715—it’s in the phone book and has been for years.

In 2016 in advance of the Doctor Strange movie, I sent his creator a highly unprofessional combination fan letter and interview request expressing my very sincere admiration for his work and basically begging to sit at his feet while he held court on whatever he wanted to talk about.

Then, in for a penny, I asked if I could bring along my publication’s videographer and maybe just hang out and take footage of him at work, and closed by saying that whether he gave me the interview, or not, I wanted to express my admiration of his work, which I have loved since I was a small child. I signed my name with a tacky flourish and then, worrying that it was illegible, printed it underneath. I put in a self-addressed, stamped envelope, for good measure. Getting an interview with Ditko, I knew, would be a huge coup. He knew it, too.

Here’s what he wrote me back:

I keep it in its original envelope, in a bag and board, in a box with the comics I love the most, Ditko’s among them.