For the past three decades, Steven Soderbergh has been American cinema’s most daring auteur.

From igniting the domestic indie movement with sex, lies, and videotape, to balancing A-list projects (Ocean’s 11, Traffic, Erin Brockovich) with star-studded mid-tier works (Out of Sight, Logan Lucky, The Limey) and more eccentric low-budget efforts (Schizopolis, Bubble, The Girlfriend Experience), to spearheading the transition to digital filmmaking—not to mention his sterling foray into TV—Soderbergh has operated at the forefront of the medium, always directing, editing and shooting with an eye toward innovation. That’ll again be evident on March 23 when he debuts Unsane, a horror feature shot on iPhones. And it’s even more true this month, thanks to his newest groundbreaking small-screen venture—which, it turns out, is best experienced not on cable television, but on your handheld device.

Mosaic is a six-part murder mystery starring Sharon Stone, Garret Hedlund, Beau Bridges and Paul Reubens that premieres on HBO on Monday, January 22. However, you can watch it right now, for free, by downloading the Mosaic app (on iOS or Android) and creating a free account, which lets you sync progress across multiple handheld devices and set-top boxes. The catch is that the TV adaptation is a linear affair arranged in (mostly) sequential order, while the app’s version is not. Rather, it presents its tale as an interactive branching narrative, one which initially grants you access to a single chapter. Then, by watching content, you unlock further chapters, as well as “Discoveries,” which are supplements (short peripheral scenes, emails, newspaper clippings and official documents) that enrich the primary storyline. Altogether, the HBO program and app afford viewers two different perspectives on the same material—which is fitting, given that POVs are central to Soderbergh’s latest triumph.

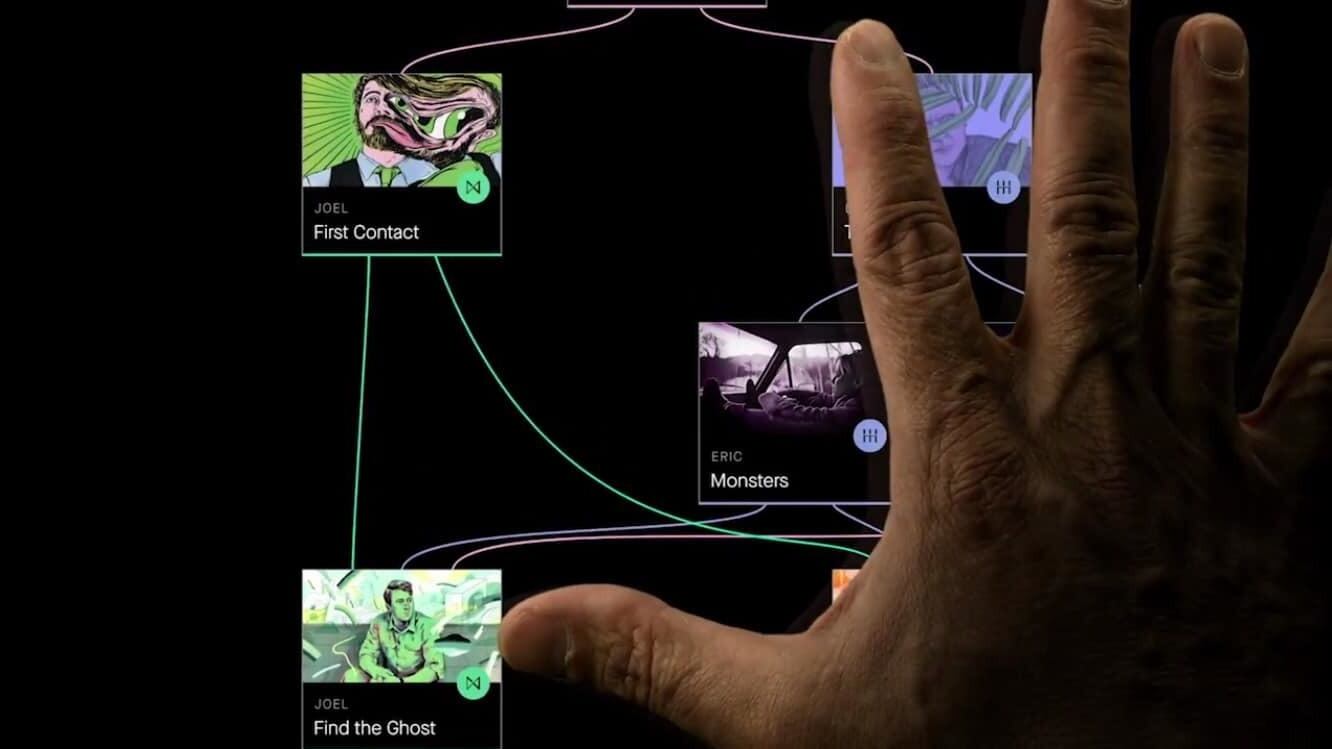

Of the two, it’s Mosaic’s iOS incarnation that’s far and away the more fascinating—and thrilling. By navigating the gorgeously designed app, which provides a branching-tree menu of chapters (and which works better on a phone than on an Apple TV, where Discoveries were more difficult to access), one is drawn into the saga of Olivia Lake (Stone), a Summit, Utah, children’s book author with one legendary hit (Whose Woods These Are) to her name. Olivia is saved from a scam artist by the intervention of Eric Neill (Frederick Weller), who becomes her fiancé, much to the delight of her friend JC (Reubens) and the dismay of her handyman Joel (Hedlund), who’s living in a barn on Olivia’s mountain estate, and who has dreams of becoming a graphic novelist. Before long, Olivia is murdered, a development that adds to the mix Eric’s sister Petra (Jennifer Ferrin), local cop Nate (Devin Ratray), Joel’s wife Laura (Maya Kazan) and friend Frank (The Knick’s Jeremy Bobb), and business partners Michael (James Ransone) and Tom (Michael Cervis).

After Mosaic’s maiden chapter (told from Olivia’s perspective), viewers are presented with two subsequent installments: one focused on Joel’s POV, and one on Eric’s. While that form may sound like Soderbergh is fashioning his own high-tech Choose Your Own Adventure, his story’s ending is never in doubt; all that’s in your control is the means by which you reach that conclusion. Sometimes, chapters boast identical scenes (if they’re crucial to the ongoing plot); other times, they repeat scenes from different vantage points to illuminate things about certain individuals. Frequently, perspectives shift mid-chapter. The order content is viewed is key, since some incidents are baffling at first, and have greater resonance only after an additional sequence (or Discovery) has been watched—for example, a line spoken by Petra during her first meeting with Joel has far different connotations after watching a Discovery encounter between her and Eric.

Soderbergh is after a 360-degree narrative—a goal that involves crisscrossing between people, doubling back on prior events, and digging deeply into his characters’ heads, replete with moments in which we hear Joel’s inner thoughts and Petra’s voiceover ruminations. Online, Mosaic is an engrossing experimentation in assembly, one that throws straightforward chronology out the window in order to make viewers muck around in its plot, sleuthing about like a detective—revisiting vital encounters and searching through just-unearthed evidence to unravel a mystery. That it begins at a point somewhere after the “beginning” and then moves backwards and forwards to expose truths about relationships and events further helps it make one feel like an active participant in what is, essentially, a preordained drama.

Written by Ed Solomon, Mosaic is, in this fractured configuration, a gripping jigsaw puzzle, one whose splintered nature generates early intrigue, and rewards taking detours—both to the Discoveries (which are announced by on-screen pop-ups, and also accessible from the main menu), and to other story branches. Moreover, that construction is repeatedly echoed by the material itself: Olivia’s famed book is a fable told from opposing perspectives; Petra creates a wall map of index cards that resembles the Mosaic branching menu; Eric says “I’ve got to go through the whole thing in order”; Joel and Frank discuss “sequential storytelling”; and others refer to “the big picture” and “pattern recognition.”

Repeated pop-culture shout-outs (to The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, Escape Plan, The Wire and Will Eisner, to name a few) give the action an additional plugged-in quality in tune with Mosaic’s cutting-edge app-narrative make-up. And Soderbergh’s circular pans (evoking the shape of Mosaic’s map icons) and shots down corridors (passageways that recall the threads connecting the menu’s chapters) further his harmonious form-content approach. Everything is deeply in sync here, with the director’s interwoven panorama conveying the complexity of lives—how they intersect with others, even as one’s own always feels like the center of the story—as well as the notion that truth is determined, and defined, by perspective.

Sharon Stone and Paul Reubens star in Steven Soderbergh's 'Mosaic.'

HBOThen, of course, there’s the rapturousness of Soderbergh’s style. Employing long takes that never call attention to themselves, Soderbergh’s camera (shot using his usual pseudonym, Peter Andrews) moves from high to low, rotates around characters, and gazes at them from upturned angles. His striking imagery is, per tradition, color-coded—with icy blues for wintry scenes, and lush reds and yellows for interior spaces—and full of reflective surfaces and blooming background light that casts foreground figures in half-silhouette. His editorial structure (completed under his other nom-de-guerre, Mary Ann Bernard) is equally exciting, deftly seguing between corresponding/conflicting points of interest to amplify suspense. Its style at once fluid, sumptuous and always speaking to the material’s larger themes (and purpose), Mosaic reconfirms Soderbergh’s unequaled grasp of filmmaking technique and ability to push it into novel realms through audacious experimentation.

As you’ve by now noticed, I’ve spoken very little about the proceedings’ actual plot, which is intentional, since giving away almost anything about Mosaic is at odds with its spirit of discovery. It’s also because, to some extent, the show is most electrifying as a formal gambit. “There is no reasoning with emotion,” states a character, and that line speaks to the struggle between intellect and emotion at the heart of this project. That tug-of-war is most acutely felt when watching the HBO version of Mosaic. When streamlined into a conventional neat-and-tidy package, Soderbergh’s show loses a considerable amount of its moment-to-moment mystery, since things are merely what they appear to be. On its own, it’s fine, but it pales in comparison to its cerebral interactive counterpart.

As an online experience, Mosaic is rich and dynamic, and considered from a logistical standpoint—including the myriad camera set-ups and takes that went into realizing its multiple-POV action—it’s awe-inspiring. But even if one’s breath is primarily taken away by its compositional dexterity, it only works, in the end, because of its great performances.

As the resentful, seething-with-rage Joel, Hedlund expresses his character’s mixed-up inner life while nonetheless remaining just opaque enough (to us, and himself) to still function as a tantalizing suspect. He’s ably complemented by Weller (smooth-talking and sleazy), Ferrin (resolved and untrusting), Bridges (arrogant and bitter), Bobb (hilariously oily), Ransone (sniveling and shifty) and Cerveris (cool and menacing). Not to mention Ratray, who’s so excellent as detective Nate he deserves his own stand-alone series.

Yet above them all is Stone, who as Olivia radiates brash-talking toughness, lingering self-doubt, past-her-prime sourness—lusting after youth, while resenting it all the while—and a genuine desire to both do the right thing and find true love. Even though it only lasts for a few episodes, Stone’s turn is something close to masterful. And in a sustained candlelit reaction to an engagement proposal, her face proves a tapestry of emotion as complex and captivating as Mosaic itself.