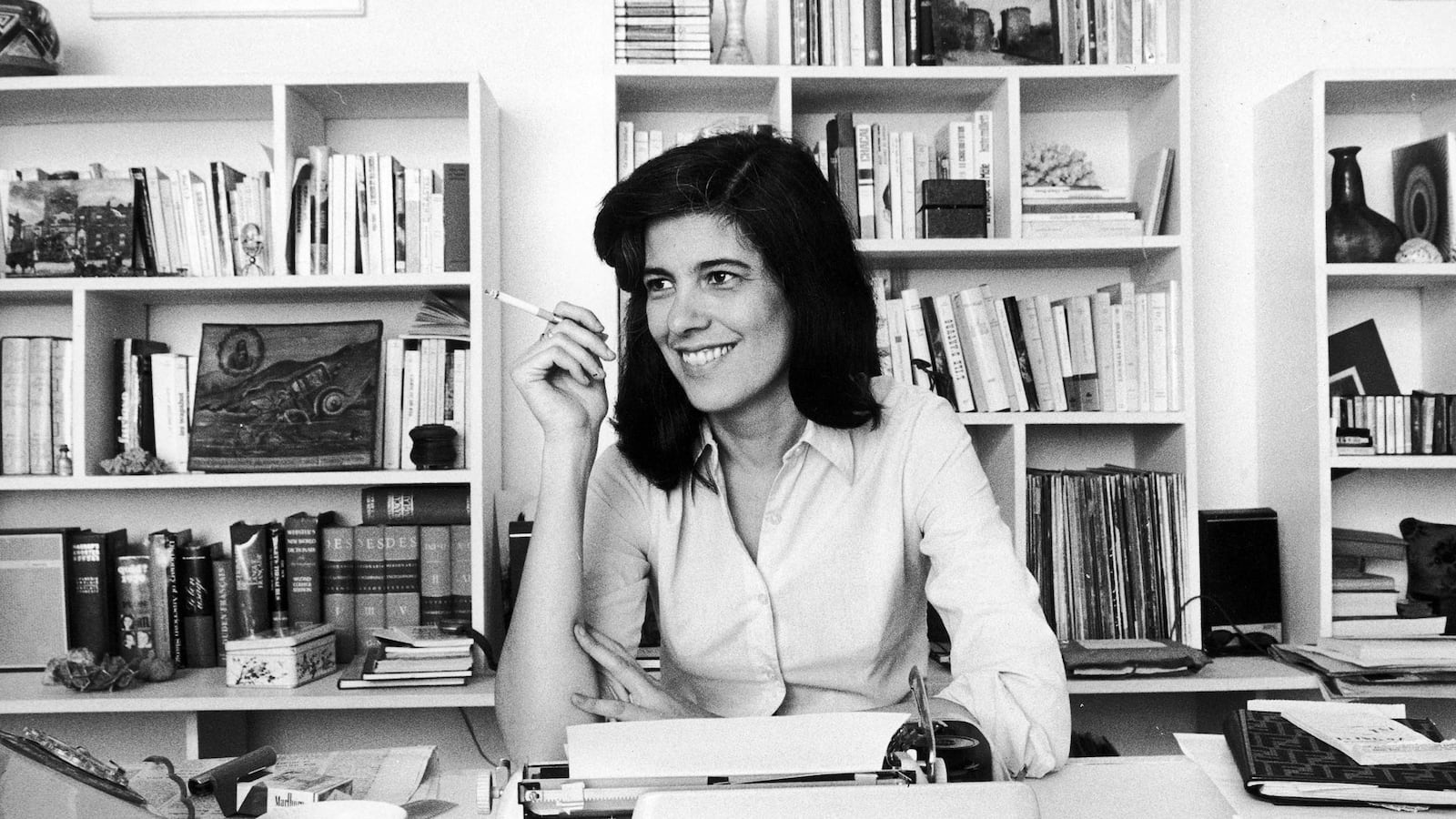

There may be no way now to explain to younger generations how exciting it was in the ’70s to see a new essay by Susan Sontag in the New York Review of Books show up in your college library. Or the thrill of finding pieces you had only heard about collected in low-priced paperback editions of Against Interpretation and Styles of Radical Will. Particularly those with the famous Harry Hess cover photo of the attractive woman with the chin-length bob gazing disinterestedly over her shoulder; the picture caused some jealous fools to dub her “the Natalie Wood of the avant-garde.”

Sontag got us to read Artaud and Cioran, to appreciate Godard’s films and Bergman’s persona, and even travel to universities where theater departments staged productions of Marat/Sade. She inspired us to flip the finger at stuffed academic shirts who frowned on our listening to the Supremes, the Stones, and the Doors. “Here,” writes Daniel Schreiber in Susan Sontag: A Biography, “was another way to think about issues—intellectual but not academic.”

It’s difficult to gauge her influence today. The subjects Sontag wrote about quickly moved into intellectual mainstream culture; by the time Newsweek and Time got around to quoting Notes on “Camp,” the quotation marks had been dropped off the word. She helped raise the level of serious discussion on film; in the mid-’60s, as Schreiber writes, to place film alongside literature and fine art “was as scandalous for most of her contemporaries as it was liberating for the new generation of artists and academics.” But well before the end of the century every college in the country had a film studies department, and no one needed to defend cinema as an art form.

Another problem with sizing up Sontag is that within a few years of the first books she was already starting to revise her popular image as “Miss Camp.” By the end of the decade, she freely admitted that she had lost interest in her early essays and was even distancing herself from the radical chic political stance expressed in such much-discussed pieces as What’s Happening in America and Trip to Hanoi. A few years before her death in 2004, she even told The New Yorker that she hadn’t actually enjoyed the experimental fiction of William Burroughs and Nathalie Sarraute that she had praised 30 years before.

Over the last 20 years of her life, she became known less as a writer and a critic than as a public intellectual like Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal, who made bold statements on sensitive topics and did cameo appearances in feature films (in Sontag’s case, as a talking head in Woody Allen’s Zelig).

“I’m sick of being Susan Sontag,” Schreiber records her as saying toward the end of her life. “I can’t get any work done … They want me to give speeches. They want me to support this political campaign or that one … I end up doing nothing but being Susan Sontag.”

It didn’t help that her style, nearly devoid of humor or irony, was easy to parody. “Susan Sontag has written,” said Mike Myers’s German TV host Dieter on SNL, “that The Munsters lie at 24 frames per second.” In Bertolucci’s 2003 film The Dreamers, set in 1968, there’s a close-up of a bookshelf filled with Sontag’s books—curiously, several of the titles had not yet been written. Our image of Sontag, Bertolucci implied, would always be frozen in the late ’60s. How galling it must have been to her to see once radical manifestos used for nostalgia.

***

First published in Germany in 2007 under the title Susan Sontag: Geist Und Glamour, Schreiber’s biography has been crisply translated into English by David Dollenmayer. It’s compact and respectful of its subject while, on the whole, honest about her shortcomings. In Schreiber’s view, “The private and the public Susan Sontag were largely the same. The image she created of herself was too compelling. Even she succumbed to it. Of course, even Susan Sontag could not always be Susan Sontag. But she always felt the need to be.”

Susan Lee Rosenblatt was born in New York in 1933. Her father, who managed a fur trading business in China, died when she was 5. Her mother married an Army captain named Nathan Sontag. She once told Rolling Stone, “I was a terribly restless child, and I was so irritated with being a child that I was just busy all the time.”

The family moved west, first to Tucson and then to Los Angeles, where Susan was bored beyond tears: “She regarded herself as the ‘resident alien’ in the family and could hardly wait to be released from the ‘long prison sentence’ that constituted her childhood.” She tried, says Schreiber, “to cut the umbilical cord to her parents mainly by way of entrance into high culture.” She succeeded.

To call her precocious would be an understatement. In her early teens she frequented the Pickwick Bookshop on Hollywood Boulevard to, as Schreiber puts it, “read her way through world literature,” by which she meant European literature.

When she was 16, Susan went on a pilgrimage to visit Thomas Mann at his home on San Remo Drive. (This must have been during a break from college; in a neat bit of detective work, Schreiber reveals her real age at the time; later Sontag would claim to have been 14 when she sought out the author of The Magic Mountain). The great Mann disappointed her; instead of Kafka and Tolstoy, he wanted to know what she thought of Hemingway. “We neither of us were at our best,” she would recall.

At 15 she began undergraduate studies at Berkeley but later transferred to the University of Chicago where, her mother told her, “You’ll only find Negros and Communists.” Mom was pretty much right. One of the lefties she met was a sociology instructor named Philip Rieff, whom she married after a 10-day courtship. She acted in college theater with Mike Nichols and learned the correct pronunciation of the names of French novelists by overhearing conversations (“I thought ‘Oh shit, it’s pronounced Proost.’”) After stints at the graduate program of philosophy at Harvard and then studies at Oxford, she turned the staid world of old-left New York intellectuals on its head by force-feeding it with large doses of French culture. “I still think of America,” she once told an interviewer, “as a colony of Europe.”

She enraged the old farts of academe by asking, “Why do I have to choose between the Doors and Dostoyevsky?”

Schreiber’s narrative was written since Sontag’s death, but it fails at helping us to assess her contribution nearly half a century since she burst on the intellectual scene. I think it can safely be said now that, like that other iconic and polarizing writer of the ’60s and ’70s, Norman Mailer, Sontag’s greatest work was clearly her nonfiction. Like Mailer, her voice as a critic and journalist was authoritative and distinctive, and like Mailer she wasted an incredible amount of time and energy noodling aimlessly with theater, film, and, for the most part, fiction.

She made it clear that she wanted to be remembered for her novels. “She saw herself as part of a larger tradition that includes Honore de Balzac, Leo Tolstoy, Marcel Proust, and Thomas Mann.” She was deluding herself. Schreiber calls her first novel, The Benefactor (1963), “a rigorously modernist text that basically must be read more than once to catch the numerous ironic references to Descartes’s meditations, Voltaire’s Candide, and the Greek myths of Hippolytus.” But I’m not the one who’s going to reread it.

With the possible exception of The Volcano Lover (1992), which was really a concession by Sontag to the old-fashioned realist novel of the 19th century, her fiction is excruciating. It’s hard to recall any of them without thinking of Kevin Costner’s proclamation in Bull Durham that “I believe the novels of Susan Sontag are self-indulgent crap.”

Her films? Her documentary on Israel, Promised Lands (1974), displayed admirable craft, but can her other three films be taken seriously? Pauline Kael, who had exactly the kind of bullshit detector that Sontag lacked, nailed Duet for Cannibals (1969) as “a hermetic, guess-what’s-real movie … about two couples and the games they play, which would be more entertaining if we could figure out the rules or discover if there was anything at stake … the other performers seem to be stranded on the screen, trying to fill in the slack of the dry, expository dialogue and looking for clues to what’s wanted of them.” Brother Carl (1971) inspired the funniest headline I’ve ever seen on a movie review: “Child Admitted,” read the Village Voice head, “Only With College Graduate.”

A critic in the Harvard Crimson summed up Sontag’s problem as a filmmaker—she was “more interested in Making Movies than in making a particular movie.”

As for Sontag’s career in the theater, Schreiber, despite himself, is brutal. Though it was directed by America’s leading avant-garde theater artist, Robert Wilson, Alice in Bed (1991) was a disaster. The play “garnered an impressively long list of negative reviews that ran the gamut from polite to malicious … One is confronted with pretentious language and a great deal of pathos. Sontag’s claim that she wrote the play in only two weeks suggests not a romantically inspired creative rapture but aesthetic dilettantism.”

Of her most famous theatrical effort, directing Waiting for Godot in the midst of a war-torn Sarajevo in 1993, one is still at a loss for words. The personal courage required to stage such a production within range of mortar shells was staggering, but the decision to stage that play—or any play—in a city of dismembered and decaying bodies is stupefying. A British editorialist called it, “mesmerizingly precious and hideously self-indulgent.”

The question must be asked whether, if not for the early essays, we would even be discussing Susan Sontag today? Certainly On Photography (1977), Illness as a Metaphor (1978), and its continuation, AIDS and Its Metaphors (1988) are worthy, but would they still be discussed if not for the lingering shadow of Sontag’s still-powerful persona?

Was she even that great a critic of pop culture? Though she enraged the old farts of academe by asking “Why do I have to choose between the Doors and Dostoevsky?” she never really had anything interesting to say about the Doors or the Beatles or even Patti Smith (whose shows at CBGB’s she frequented). And by the way, if we really are just a colony of Europe, where did the rock and roll she professed to love so much come from?

Perhaps more enduring than her writings will be her role as the last public intellectual. She sent shock waves through the ranks of the new and old left in 1982 when, at a Town Hall meeting of writers and activists in support of the Polish Solidarity movement she proclaimed, “We should have understood a very long time ago that Communism is Fascism … with a Human Face.”

Then, in a piece for The New Yorker after 9/11, she asked rhetorically, “Where is the acknowledgement that this was not a ‘cowardly’ attack on ‘civilization’ or ‘humanity’ or ‘the free world’ but an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed super power, undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions? … if the word ‘cowardly’ is to be used, it might be more aptly applied to those who kill from beyond the range of retaliation, high in the sky, than to those willing to die themselves in order to kill others.” But few who quoted her words included the closing sentences: “Let’s by all means grieve together. But let’s not be stupid together.”

Whatever the final record of her successes and failures, whichever of her works survive to future generations, Susan Sontag, finally, fulfilled the obligation of a public intellectual to keep her head when all about her were losing theirs.