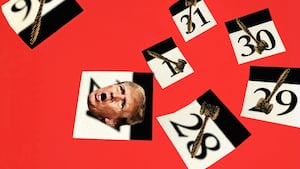

Former President Donald Trump faces state charges brought by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg of falsifying business records in order to interfere with an election. The prosecution arises from Trump having allegedly concealed $130,000 paid to actress and director Stormy Daniels in the months before the 2016 presidential election in an effort to avoid worsening the storm of bad publicity accompanying the airing of a videotape in which he brags about grabbing women by their genitals without their consent.

The case had been scheduled to commence March 25—making it the first criminal case to be tried against Trump. Even though it has now been postponed—it still appears likely to be the only one of the four criminal cases against Trump to have a chance of being tried before the 2024 election.

But the March 25th start date has now been delayed amidst a flurry of motions filed by Trump’s defense lawyers, claiming that just-produced discovery documents will make it impossible for them to prepare in time. Among the remedies they’ve requested are a delay of the trial and even dismissal of the charges.

The new documents involve some 100,000 pages—a significant amount, but not a particularly overwhelming number in 2024, when data disclosure is measured sometimes in terabytes.

Much of the late production can be attributed to the fact that the case was previously in the hands of federal prosecutors from the Southern District of New York, who had looked at the potential charges years before Bragg brought his case. While the exact details of that delay is still unknown, it certainly appears that the responsibility for another potential delay of a Trump trial rests with the U.S. Department of Justice.

But complaints against the federal prosecutor don’t explain Trump’s other argument for dismissal and delay: a documentary about Daniels’ life that dropped Monday on Peacock.

In their motion, Trump’s lawyers argue that Bragg’s prosecutors should be blamed for hiding the release date from Trump, and also be held responsible for the film potentially prejudicing the jury pool by being released so close to trial and jury selection. Trump also asked that the federal judge overseeing the trial—Judge Juan Merchan—exclude testimony from Daniels, Michael Cohen (Trump’s former lawyer, who is alleged to have arranged the payment to Daniels) and Karen McDougal (a former Playboy model who also may have received hush money payments) as well as a ban on the playing of the Access Hollywood video.

Judge Merchan denied the efforts to keep Daniels, Cohen and McDougal off the witness stand—but gave Trump a partial victory by ruling that the Access Hollywood tape could only be asked about, but not played for the jury. Trump’s lawyers, however, will have to be careful in their cross-examination of any aspect of the Access Hollywood video, because overreaching could easily open the door to Judge Merchan changing his mind on whether the video can be played.

Merchan’s denial of the attempt to exclude witness testimony was a no-brainer given the central role that both Daniels and Cohen play in the case and McDougal’s value as a witness to the same pattern of paying for silence. The arguments lacked any legal merit and only served to play up Trump’s fear of these witnesses rather than serve any valid legal argument. If anything, Trump is broadcasting to the world that these witnesses have testimony that can really hurt him.

Too often, the term “prejudicial” is thrown about carelessly when it comes to whether evidence in a case should be admitted. It’s a careless use of the term because the legal standard is not whether evidence is prejudicial—meaning it may hurt one side or the other—but rather whether the prejudice outweighs the value—the probity of the evidence.

If the standard were only whether it were prejudicial, then most evidence would get thrown out, since the only reason it is being offered at all is because it helps one side and presumably hurts—prejudices—the other side. So here the probity of these witnesses is obviously high. And as is often the case, so too is the prejudice.

Stormy Daniels enters federal court in New York City.

Lucas Jackson/ReutersTrump’s argument that the release date of the documentary about Daniels should be held against the prosecution is illogical on its face because the prosecution didn’t make the movie. Nor do they control its release date.

To argue that they had a duty to tell Trump about the release date is fanciful, even assuming they knew about it ahead of Trump. It’s fanciful because that kind of logic would mean that no fair jury could be picked while there is publicity around the events of the trial. For any of Trump’s cases, that would likely mean Trump would be amenable to a trial only after his cases were no longer of public interest which is not likely to ever happen.

The weakness of Trump’s legal argument is further evidenced by the fact that this is in many ways a documents case, where ledgers showing where the money went and how it was characterized is what makes the case. Witnesses like Daniels, Cohen and McDougal simply corroborate the paper trial and bring it to life.

And that is exactly what Trump and his lawyers fear. They would like to have a case just about paper where they are free to criticize the credibility of witnesses without pushback from the witnesses themselves. They have watched for years as Michael Cohen told essentially the same story over and over again. They know they cannot make any dents in his testimony.

Trump and his lawyers will be even more unhappy if they actually watch the documentary about Daniels. In it, she comes across as a sympathetic and brave person who—like Michael Cohen—has had her life gravely upended and ruined by her association with Trump.

These facts are what they fear will come across to the jury, and no amount of legal maneuvering can cover up the simple human truth that these witnesses will speak about the real practices of Donald Trump.

Alvin Bragg’s prosecutors can be confident that those truths will add immeasurably to the strength of their case.