I saw Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs for the first time at the Visulite Theater in Charlotte, N.C., the week it was released, between Christmas and New Year’s Day 1971. I even remember where I sat—halfway back in an almost empty theater—and that I attended the earliest matinee. In those days, theaters weren’t cleared between shows, so I sat through the movie twice. This was only partly intentional. Mostly it was the inertia of shock. I was so stunned by Peckinpah’s film—it was like someone had knocked the wind out of me—that when it was over, I couldn’t get out of my seat. So I sat there, staring at the blank screen. Then the film began again, and I saw it a second time. And that time I started studying it, desperate to discover how Peckinpah had done such a number on me. I’d never seen a movie like Straw Dogs. Neither, I’ll wager, had anyone else.

I wasn’t exactly blindsided. The Wild Bunch, a Peckinpah Western bookended by shootouts with more bloodletting than any 20 ordinary Westerns combined, taught me to expect scenes of violence as stylized and choreographed as anything in a Balanchine ballet. No one controlled a movie camera and an editing room with more élan than Peckinpah. But he didn’t merely aestheticize violence. Blood spilled in one of his movies is never paint. The crosscutting and the slow motion are there to draw you in, to make you forget, at least for a little while, that you’re watching actors at work. And ultimately, he makes you feel the catharsis in violence, the adrenaline rush, and the shame in that. Peckinpah’s true genius lay in his ability to make art out of the contradictions in his own heart. At his best—and when he died in 1984, at 59, he left behind four or five of the best movies anyone has ever made—he knew how to etch his unresolved inner conflicts right into those 70mm screens. He got away with entertaining you and disturbing you all at once, because he worked in a Hollywood that we no longer recognize, a world full of mercenary studio bosses who still lived on their instincts and not on market research. Still, in that day or any other, Straw Dogs was in a class all its own.

I’ve just watched the movie again, on a splendidly clean Blu-Ray disc (whose release is timed to coincide with last week’s debut of a remake starring Kate Bosworth and Alexander Skarsgard (in case you were wondering, a remake of one of the most accomplished, and certainly most personal films to ever come out of Hollywood, is good for about $5 million in its first weekend out). After a second go-round, I can say that while my first reactions were those of a very young man, they weren’t misplaced. Forty years later, the movie has lost none of its bludgeoning power.

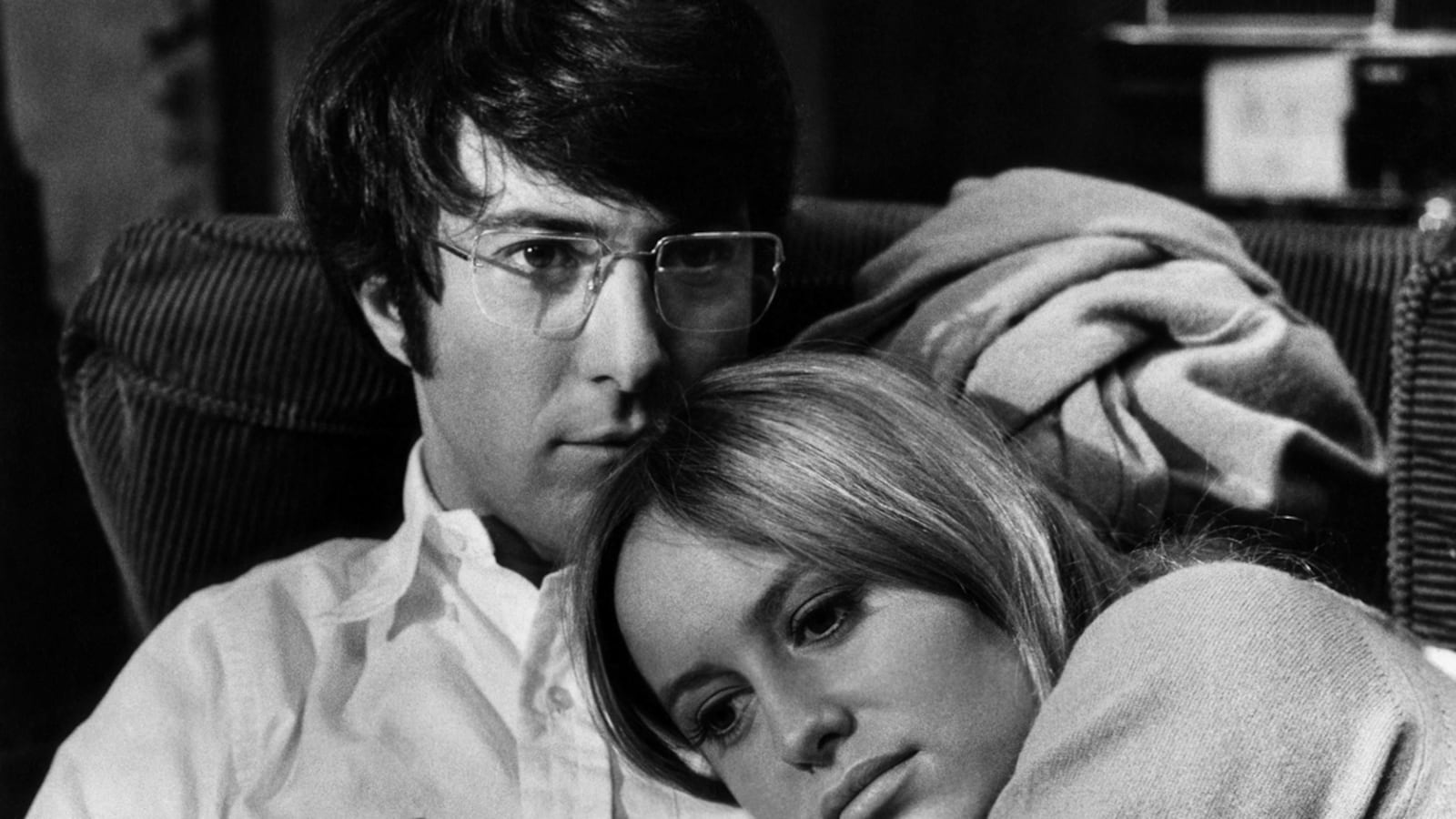

The plot of Straw Dogs is fairly simple. A young couple moves to a rural English town and rents a house. David Sumner, an American, is an astrophysicist with a grant to do research. His wife, Amy, is English, originally from the town where they now live. In the opening shots, they run into one of her old flames, a handsome, hulking man who dwarfs and plainly intimidates David, played by Dustin Hoffman at his squirrelly, brittle best. Amy, played with a teasing sultriness by Susan George (who delivers by far the film’s best performance), only halfheartedly resists her old boyfriend.

The Sumners, we find out soon enough, have a bad marriage, with nothing much in common other than sex and a sort of teasing affection. Moreover, David is apolitical and apathetic. He has come to get away from the violence rampant in the States, and he pretends to be proud of not taking a stand or getting involved. When one of the villagers asks him if he saw any of the urban rioting or campus violence, he quips, “Only between commercials.” No one laughs.

It’s when he hires Amy’s old boyfriend and another couple of locals to work on the Sumners’ garage that things go on the boil. The men intimidate David and flirt with Amy. Over the course of the film, the marriage frays and the men outside close in, psychologically at first—and then quite literally. Luring David away on a snipe hunt, two of the workmen return to the house and rape Amy, who signals her trauma and her utter alienation from her husband by not telling him what’s happened. Soon after, as they return one evening from a church social, David hits a man with his car and takes him in. The man, who has a history of mental incarceration, is being sought by the villagers, who suspect him of killing a young girl. When David won’t let them take the man and then bars them from his house, they attack with rocks, knives, and a shotgun. A pitched battle ensues and at last David finds the courage to retaliate. At the end of the fight, he’s the only one left alive.

Straw Dogs is based on a good novel by Gordon Williams, The Siege of Trencher’s Farm. But what’s most interesting are the considerable differences between the book and the film, and specifically how Peckinpah and his co-screenwriter, David Zelag Goodman, changed the story, by making the characters younger, giving the wife a past in the village, dwelling on the ways in which the workmen slowly encroach on David Sumner’s turf. The real genius of the screenplay is how the writers make some plot elements more specific (Amy’s relations with her old flame) and others teasingly vague (in the novel, the man David protects is a convicted child molester and murderer, but in the film, we’re never exactly sure what he did in the past, which somehow makes him even creepier). The most ironic change is the final battle. In the novel, the climactic fight at the farmhouse eats up half the narrative. Peckinpah, for all his reputation as “Bloody Sam,” the maestro of screen violence, cuts that part by at least half. He’s much more interested in showing us how David and Amy’s world falls apart in little bits and dribbles. This is a movie about marriage at least as much as it is about territorial imperatives. And this emotional freight, ultimately, makes the violence at the end not only more inevitable but also more horrible. The biggest difference between book and movie, though, is that the rape scene is nowhere in the novel.

The rape is, and probably always will be, the most controversial part of the film. People will argue about it because it’s so graphically discomfiting—oh, but what a prissy word to describe a scene that’s so beautifully acted, photographed, and edited that you can’t tear your eyes away and with every second you feel more wretched for not having done so. But the true controversy here lies in the fact that Peckinpah so willfully crosses a taboo line and shows Amy ultimately relenting and accepting her old lover—in the first rape. When the second man steps in for a turn, she’s all but destroyed. Arguably, a woman so completely alienated from her husband and assaulted by an old lover might have mixed feelings. But art is not built out of a thesis. Art depends for its effects, for its persuasiveness, on inevitability. If you have to defend a scene like Amy’s rape, that’s not art, that’s just argument. That said, the aftermath is completely moving, especially the scene where Amy has to walk by her attackers at the church social and we watch her fall to pieces, as little shreds of the rape scene are edited into the stricken close-ups of her crumbling face. Peckinpah never gave a woman more sympathy in any of his other films. Amy becomes the only character in the film about whom we truly care.

I can’t say I love Straw Dogs. I admire its technique—in the first 10 minutes of the movie, we are introduced to every major character, indeed, to every major prop, including an antique metal man-trap once used on poachers, that will play a crucial part in the final battle. The speed and conciseness with which he worked—if one isn’t careful, one could start babbling here about Aristotelian unities—are breathtaking. But this was one of those things I noticed on the second viewing. The first time around, there’s no room in your brain for any such dissection, because Peckinpah has so thoroughly harnessed his dexterity in the service of his story that you never once think about process.

What’s most interesting is that there’s almost no one in it to like. Amy is, at most, a pitiable woman trapped in a marriage that she has no idea how to fix. David is condescending, arrogant, and cowardly. The men outside the house are just a thorough pack of rogues. You know no good will come of any of this, but the inevitability of the tragedy bewitches you like a swaying cobra. Bewitches and implicates is more like it, and in that nasty cross-wired combo lies the movie’s considerable power. Overwhelming and insidiously powerful, Straw Dogs is a movie that first unnerves you, then beats you up and kicks you gasping to the curb.

Step by gentle step, shot by shot, Peckinpah backs you into a corner. By the end he has you rooting for David with all you’ve got. Anyone who’s ever put up with bullying and intimidation, anyone who’s ever let a situation get out of hand because they weren’t quick enough or smart enough to smother trouble before it starts—anyone who’s ever been backed into any kind of corner—wants David Sumner to kill those men, maybe more than he does. After all, he doesn’t even know they’ve raped his wife.

At the same time, Peckinpah is leaning over your shoulder, whispering that David has brought a lot of this on himself. If he hadn’t put up with their bullying for so long, if he’d stood up to them earlier, if he’d been a little more self-aware at the very least—and really, at the end, is he any better than the men he’s killed? By making his main character a brilliant mathematician, a man of breeding and taste who reflexively tunes the car radio to the classical station, and by setting this brutal story in a quaint English village, the very home and cradle of what we call civilization, Peckinpah clearly wants us to understand that what we call civilization is everywhere as thin as a layer of paint. Give him the two hours it takes to watch Straw Dogs, and he’ll make a believer out of you, too.