The travel ban is constitutional.

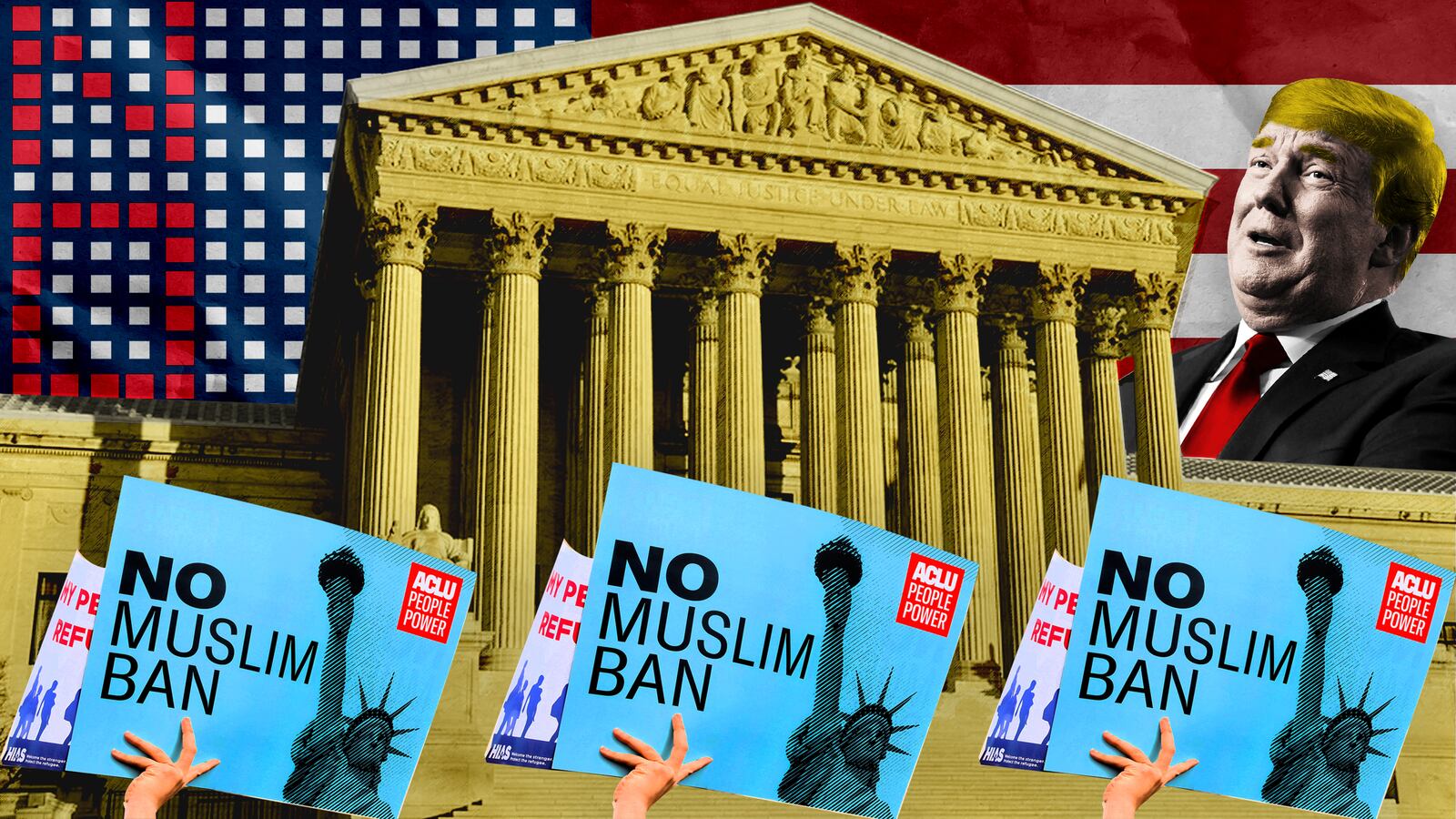

After over a year of litigation, the Supreme Court upheld Donald Trump’s signature security initiative, which bans travel to the United States from five majority-Muslim countries and two others, by a 5-4 decision.

Even though Trump called it a “Muslim ban” on multiple occasions, even though it is unprecedented in breadth, and even though it permanently bans 150 million people from entering the United States, mostly on the basis of religion, the Court put those facts aside because a president’s decisions on national security are subject to a very low standard of review by the Court.

Writing for the Court in Trump v. Hawaii, Chief Justice John Roberts skillfully demolished the two arguments against the ban: that it was an excess of presidential authority, and that it unconstitutionally targeted Muslims. In both cases, the reasoning was the same: in a different context, perhaps the Court would look under the hood at what Trump is really doing here. But because this is supposedly about national security, it won’t.

First, Chief Justice Roberts analyzed the relevant provision of the Immigration and Naturalization Act and concluded that it “exudes deference to the President in every clause.” The president has extremely broad authority to regulate foreign nationals traveling to the United States in the name of national security, Chief Justice Roberts said, and so even the unprecedented nature of the ban—its duration, its size, its overbreadth—is basically irrelevant.

Ultimately, he wrote, “plaintiffs’ request for a searching inquiry into the persuasiveness of the President’s justifications is inconsistent with the broad statutory text and the deference traditionally accorded the President in this sphere.”

The same reasoning was used to refute the second claim: that the travel ban unconstitutionally discriminates against Muslims.

Once again, the Court held that a very low standard of review was appropriate. Most serious freedom of religion cases require that the government show a compelling state interest to act and a narrowly tailored response to that interest. The travel ban would surely violate the second part of that test: it is wildly overbroad, the very opposite of narrowly tailored.

But, Chief Justice Roberts wrote, that standard of review doesn’t apply here.

Quoting an earlier decision, he wrote “the upshot of our cases in this context is clear: 'Any rule of constitutional law that would inhibit the flexibility [of the president] to respond to changing world conditions should be adopted only with the greatest caution,’ and our inquiry into matters of entry and national security is highly constrained.”

As a result, Chief Justice Roberts only applied what is known as rational basis review: “whether the entry policy is plausibly related to the Government’s stated objective to protect the country and improve vetting processes.”

And of course it is. The travel ban in this case was the third version of the ban. The first (apparently written by Stephen Miller, also the architect of the family separation border policy) was laughably unconstitutional, even incoherent. The second—which Trump called “watered down”—was a little better, but not much.

But by the third version, the Trump administration had had time for a thorough review by the Department of Homeland Security, a negotiation process with several of the targeted countries, and even the addition of two non-Muslim countries, North Korea and Venezuela. (Those two countries were not part of the challenge.) That all generated a lot of paperwork, all of which contained plenty of “plausible” reasons for the travel ban.

Once again, the standard dictated the outcome. Because of that “rational basis” standard, the Court took the Trump administration at its word. The administration cooked up rationales for the ban, and the Court ate them up.

In sum, the Court said:

<p>The Proclamation is expressly premised on legitimate purposes: preventing entry of nationals who cannot be adequately vetted and inducing other nations to improve their practices. The text says nothing about religion. Plaintiffs and the dissent nonetheless emphasize that five of the seven nations currently included in the Proclamation have Muslim-majority populations. Yet that fact alone does not support an inference of religious hostility, given that the policy covers just 8% of the world’s Muslim population and is limited to countries that were previously designated by Congress or prior administrations as posing national security risks.</p>

What about all of those times Trump made outrageous, false, and defamatory statements about Muslims, and offered them as the real reason for the ban?

Chief Justice Roberts quoted the same odious statements we’ve heard a hundred times: “Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” “Islam hates us.” And so on. But, once again, if all you’re looking for is a rationale “plausibly related” to a legitimate government interest, none of that matters.

In short, the Court isn’t going to go looking for the truth here, because national security is a presidential prerogative. If the government offers a plausible explanation, that is enough.

That was not enough, of course, for the Court’s four liberals, who joined in a dissent written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Justice Sotomayor’s dissent refuted the main claim of the Chief Justice’s opinion: that the context of national security means that courts’ roles are limited. On the contrary, she held, full judicial review is required precisely when security is proffered as a justification for targeting a disliked religious group:

<p>The United States of America is a Nation built upon the promise of religious liberty. Our Founders honored that core promise by embedding the principle of religious neutrality in the First Amendment. The Court’s decision today fails to safeguard that fundamental principle. It leaves undisturbed a policy first advertised openly and unequivocally as a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” because the policy now masquerades behind a façade of national-security concerns.</p>

To many observers, Trump v. Hawaii looks a lot like one of the most infamous cases in Supreme Court history, Korematsu v. United States. Decided in 1944, that case, too, was about the conflict between national security and civil rights, as the government forcibly relocated 120,000 Japanese Americans to concentration camps during World War II.

Perhaps surprisingly, the Court’s opinion took this opportunity to utterly refute Korematsu, which had never been technically overturned.

First, the Court said, “Korematsu has nothing to do with this case. The forcible relocation of U. S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority. But it is wholly inapt to liken that morally repugnant order to a facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission.”

But, the Court continued, “the dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—‘has no place in law under the Constitution.’”

That’s all well and good, but as Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her vigorous dissent:

<p>This formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue. But it does not make the majority’s decision here acceptable or right. By blindly accepting the Government’s misguided invitation to sanction a discriminatory policy motivated by animosity toward a disfavored group, all in the name of a superficial claim of national security, the Court redeploys the same dangerous logic underlying <em>Korematsu</em> and merely replaces one “gravely wrong” decision with another.</p>

Speaking, no doubt, for horrified moderates and liberals throughout the country, she concluded: “Our Constitution demands, and our country deserves, a Judiciary willing to hold the coordinate branches to account when they defy our most sacred legal commitments. Because the Court’s decision today has failed in that respect, with profound regret, I dissent.”