This week, the Supreme Court upheld Trump’s exceptions to the Affordable Care Act, which will allow universities and employers to deny insurers free birth control due to moral objections. The outcry from women’s rights advocates was swift. Many insisted that contraception is an imperative part of health care for women.

On Twitter, former California congresswoman Katie Hill was quick to note that birth control does more than just prevent pregnancies. It also helps to treat some conditions like endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome.

“Nothing to do with contraception,” Hill wrote. “Just with health, & preventing unimaginable pain. Clearly, people still don’t give a shit about women.”

The ruling also resurfaced a 2017 tweet from Halsey, when the singer responded to the far-right podcaster and noted creep Stefan Molyneux’s assertion that “birth control is not healthcare.”

“Birth control stops my excruciating pain + scar tissue cementing my organs together you thick fucking imbecile,” Halsey shot back, using clapping hands emojis to punctuate her thoughts.

Both Hill and Halsey speak the truth. Birth control has allowed generations of women to live their lives unencumbered by a potentially unwanted pregnancy. That freedom has long irked the religious right, who do the most to ensure that birth control becomes damn hard to obtain—especially for the most vulnerable American workers.

Elizabeth Siegel Watkins, the University of San Francisco professor and author of On the Pill: A Social History of Oral Contraceptives, has studied the marketing of birth control since the 1960s.

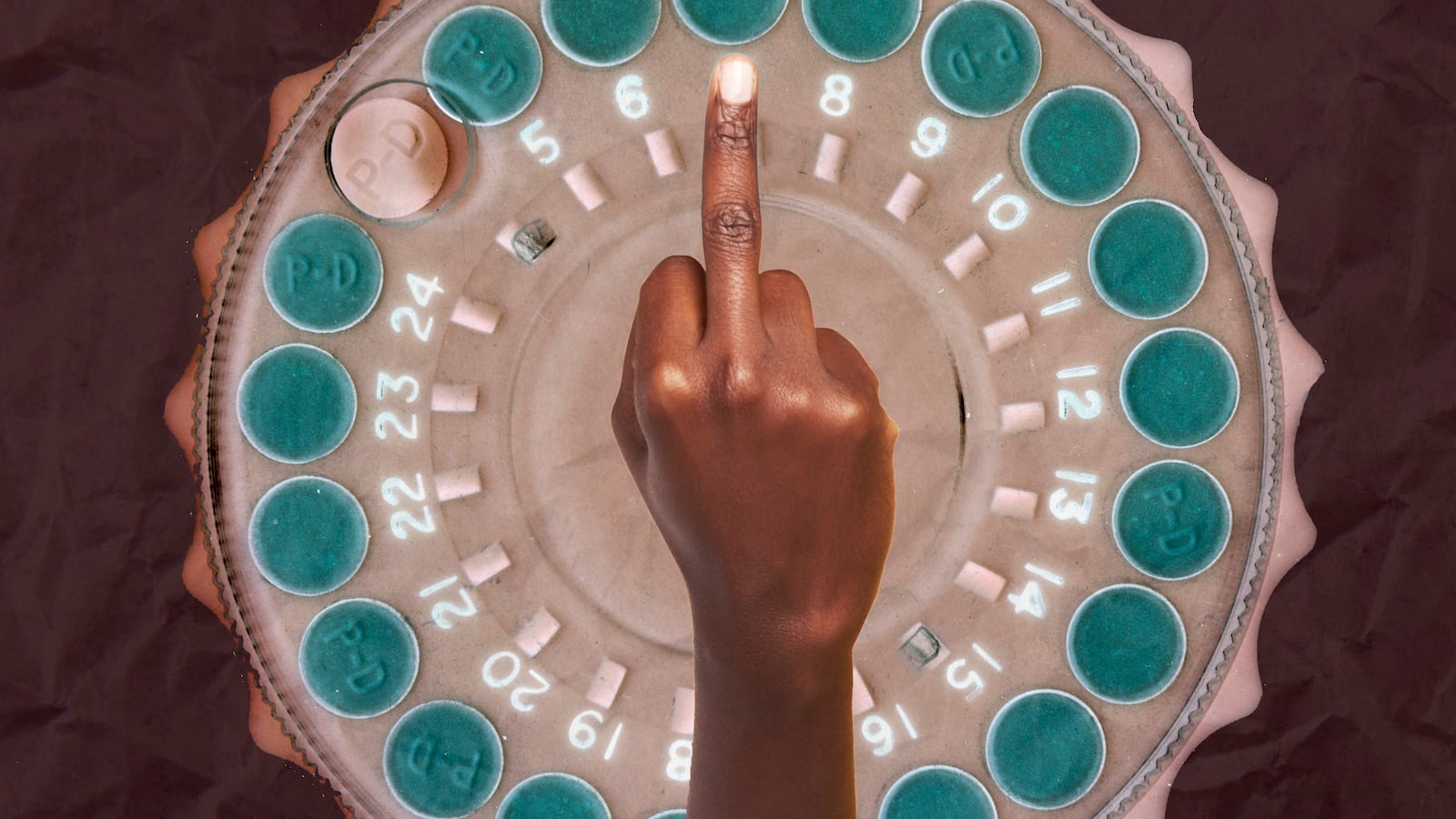

For most of the latter half of the 20th century, pharmaceutical companies were obligated to run ads for products only in medical journals, and those campaigns promoted the pill as a means of family planning.

In the 1990s, once companies were able to market to customers in general magazines, Watkins noted that the pill became known as a “lifestyle drug,” and advertisements began to focus on its lesser-known benefits, including treating acne, shortening periods, and eliminating discomfort from hormonal disorders.

In a 2012 article, Watkins cites the British Medical Journal definition of “lifestyle drug” as “one used for ‘non-health’ problems or for problems that lie at the margins of health and well-being… . A wider definition would include drugs that are used for health problems that might be better treated by a change in lifestyle.”

But, as Watkins notes, “birth control pills are not cosmetic, enhancing, recreational, or discretionary but confer a significant health benefit (the avoidance of pregnancy) on their users.”

Still, since the 1990s, many young women have explained away their birth control use as “for acne” or “lighter periods.” They should not have to, but these rationalizations can shield users from slut-shaming and anti-birth control rhetoric.

Unless you are one of the one in 10 women who suffers from endometriosis, you might not be aware that hormonal pills can drastically reduce the pelvic pains or intense cramps that count as side effects.

I have watched birth control radically improve the lives of a few friends of mine. They live with endometriosis, a chronic and misunderstood condition for which there is no lasting cure. It feels unimaginably cruel to rescind the only barrier they have against their pain just because a few millionaire company owners seem way too invested in purity culture.

Do you want to know why I take birth control? I hope not, but I’ll tell you anyway: like approximately 12 percent of American women, I’m on the pill so I don’t get pregnant. That’s right, I take it for the exact thing they named the medicine after. I do not want to give birth to a baby in nine months.

I use birth control because my friends who have kids tell me they cannot go to the bathroom without a tiny human following them in. I use it because I appreciate that my mother always leaves the last bite of a dessert we are sharing for me, and I’m not ready to sacrifice that morsel for my hypothetical daughter just yet.

But why should the reason matter? Legally and morally, shouldn’t women be allowed to control what happens to their bodies not just when they’re ill and languishing in bed, but also when they just plain feel like it? Do people really need the mental image of a woman suffering in bed to validate contraception as essential health care?

It’s reminiscent of reading headlines about potential abortion bans being even more disgusting because the act would also be illegal in the case of rape or incest. Victimized women are seen as model patients who deserve exclusions to laws.

But there are endless reasons a woman might choose to terminate a pregnancy, and every one is valid. She does not need to go through a traumatic experience to “earn” a basic civil right.

As the journalist and author Linda Greenhouse has explained, the medical community banded together to decriminalize abortions in the 1970s not necessarily because it was thought of as a human right, but because the prevalence of illegal abortions were a public health disaster. This roundabout reasoning may have been true for the era, but it does little to normalize safe, legal abortions.

While the burgeoning women's rights movement and sexual revolution also encouraged the public to support the decriminalization of abortion, Greenhouse also adds that two sensationalized cases of children being born with birth defects—a measles outbreak in Germany and the 1961 Thalidomide scandal—amplified the idea of abortion as a heartbreaking last solution to a disastrous pregnancy.

It is easy to feel sympathy for such dramatic instances, but not every abortion needs to be justified by trauma.

When the hashtag #MeToo went viral in late 2017 and a deluge of women began sharing their stories of abuse and harassment online, the journalist Alexis Benveniste tweeted, “Survivors don’t owe you their story.” It should not take a well-reported, elegantly written exposé on some actor you loved in high school’s shit behavior to recognize the insidious nature of violence against women.

The woman who uses birth control to treat a hormonal condition is no more or less noble than someone who is on the pill because they don’t want a child. In the middle of a global pandemic and economic collapse, can you really blame someone who would rather not be a mother right now?

To any new pro-choice converts who have been swayed by the point that there are multiple reasons to go on birth control—thank you for your budding support. I hope to see your masked face at the next protest. Now, please mind your own business.