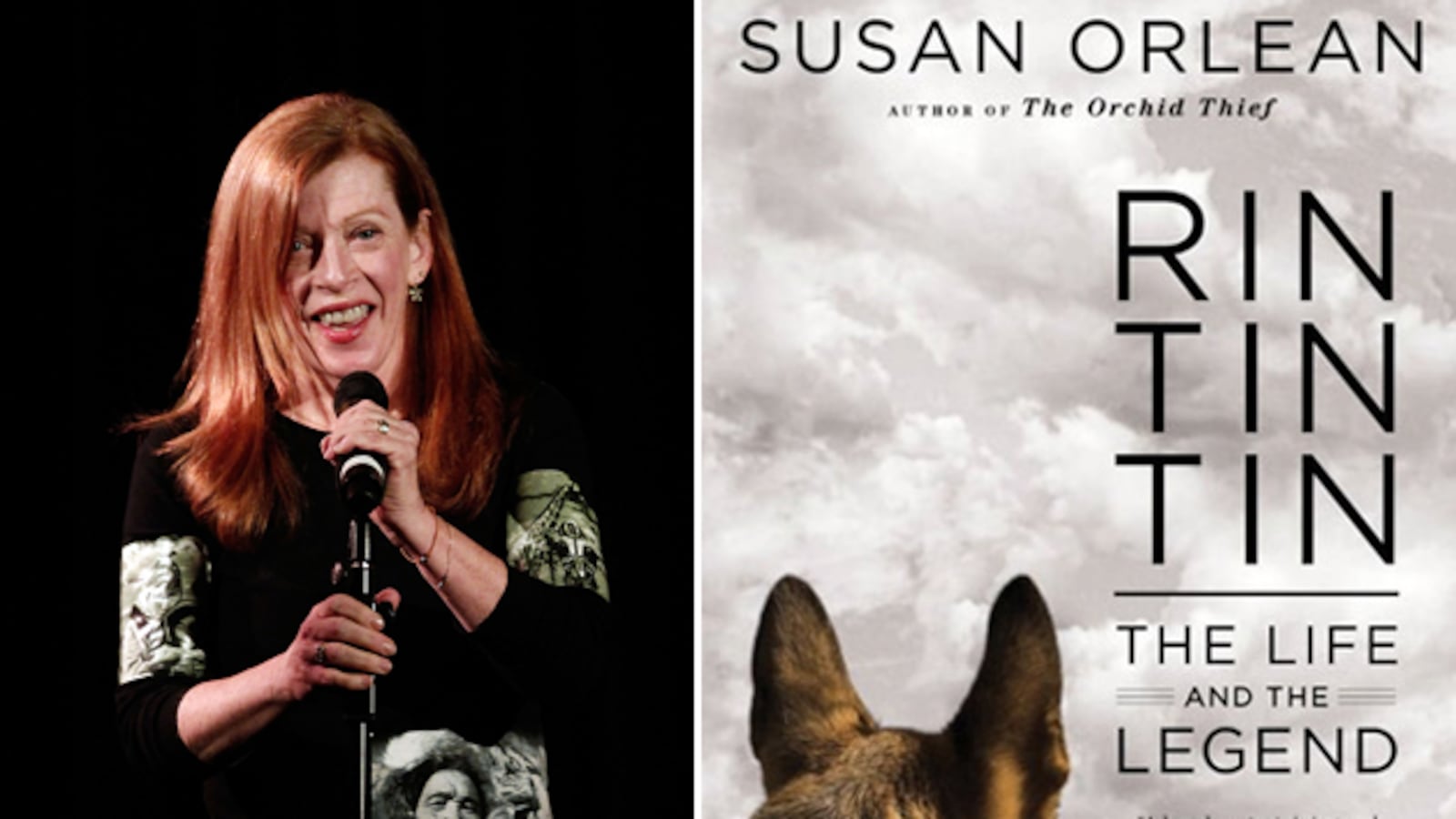

Susan Orlean never sets out to be the quirky one—it just kind of happens. A staff writer at The New Yorker, Orlean is drawn to offbeat subjects, and she chooses them instinctively. The inspiration for her latest book was a fleeting feeling, a spark of realization when she came across a name she hadn’t heard in years. It was a famous name, one that has been kicking around the cultural consciousness for almost a century, and it made her sit suddenly upright in her chair. It was the name of a dog.

Orlean soon became fascinated by Rin Tin Tin, the nimble German Shepherd who leaped to fame in a string of wildly successful silent films in the 1920s. Somehow—she wasn’t sure how—the dog re-emerged time and again (albeit in the form of his descendants) in the newest mediums of the day: “talkies,” vaudeville, television, videocassettes.

Her book, which became a passion project for the better part of a decade, drew some skepticism. “If you say to someone you’re writing a book about a dog, it’s just going to sound trivial, or kitschy—nothing of any real seriousness,” Orlean says in an interview from her home in Los Angeles. “And I knew I had to contend with that. But once I started writing, I knew that anyone beginning the book would know instantly why there was more to it.”

Indeed, Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend, begins darkly. Rinty, as he eventually became known to millions of fans, was born on a World War I battlefield in France. His mother, a member of the Germans’ corps of war dogs, was abandoned in a burnt-out kennel when Allied troops pushed the Kaiser’s forces back east. By a stroke of fortune, the litter was found by Lee Duncan, a California boy who had a soft spot for animals and an orphaned past himself. Duncan cared for the young dog during the war (not an easy feat), brought him back to the U.S., and trained his new companion religiously. Then he caught the Hollywood bug and managed to get their six paws in the door at Warner Bros., the new studio in town. Rinty became a star almost overnight.

In his heyday, the canine’s popularity was hard to overstate. On screen, he was remarkably expressive, and impeccably trained by Duncan. Rinty’s face, Orlean writes, “was more arresting than beautiful...as if he was viewing with charity and resignation the whole enterprise of living and striving and hoping.” In the world of silent film, this pup spoke volumes. His films, sprightly action flicks with clear lines between good and evil and a noble hero, touched a chord in a post-war America. Rin Tin Tin was even the rightful winner of the first Academy Award for Best Actor. (The Academy, brand new and loath to be viewed in such an undignified manner, mussed with the votes in order to produce a human champ.)

Rinty died in 1932, but new dogs, each trained by Duncan, kept the name alive, and their fame was constant even through that turbulent era. Across the ocean, in 1942, in her diary Anne Frank pined for a dog just like Rin Tin Tin while trapped in an attic. By the 1950s, when the hugely popular TV show The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin debuted, it was clear that the legend had transcended any one dog: Rin Tin Tin IV, the official heir, was barely used. Instead, the work of canine acting was farmed out to other German Shepherds.

The poignancy of this strange and unpredictable legacy, Orlean later realized, is what made her snap to attention almost 10 years ago. How could one dog come to mean so much? How had he become immortal? Rinty had come to stand for something important: nobility, vitality, a certain scrappy stickwithitness. “The stuff that stays with us and manages to outlive its limits is what drew me to this story,” Orlean writes, “and what I hope might explain something about life to me.”

The book is quintessentially Orlean: a seemingly shallow topic plumbed to remarkable depth. Her work, an editor once told her, is a high-wire act; because there is no obvious hook to much of it, the pleasure is in the precarious act of storytelling itself. That requires a skillful hand. “If you don’t do a story like [mine] well,” Orlean admits, “it’s a disaster.” And though she has the luxury of letting her own inquisitiveness guide her choices, for every article she writes about a roving gospel choir or a bunch of female surfers in Maui, there’s an inherent sales pitch throughout. “I want to grab you by the collar,” she told a group of students at Columbia recently, “and say, ‘I know you’re not interested, but it’s interesting!’”

The germ for Orlean's best-known work, The Orchid Thief, was a small item in a Florida newspaper that caught her fancy with its uncommon mix of words. The book, released in 1998, is a non-fiction tour-de-force. Wrapped in a tale of petty crime, botany, and modern-day Native American relations is a meditation on the origins of personal obsession. The film version, Adaptation, was nominated for four Oscars; Meryl Streep played Orlean.

Orlean pulls off a similar trick with Rin Tin Tin. It’s an historical account, almost a biography, of a famous canine actor, but Rinty is also an entry point into discussions about what makes American pop culture tick; our changing relations with pets and animals; and, what it means to die.

Orlean was speaking on the phone from L.A., where she has recently relocated with her husband and son. For a woman so closely associated with New York—she has been with The New Yorker since 1992, and her 50-plus acre Hudson Valley home, overrun with farm animals, is the source of much amusement to her fans—the move was jarring but not unwelcome. L.A. has been amusing, she says. “It’s just a funny place...It’s like moving from Mars to Venus.” With her writer’s eye, Orlean delights in the spectacles that others would find depressing: the women with too much plastic surgery, the gaudiness of a town built on entertainment. In the book, too, California pops. Hollywood was a start-up when Rin Tin Tin made his mark there, a new industry that hadn’t yet disassociated from the competing entertainment ventures of carnival shows.

Asked what her next book might be about, Orlean is baffled at the very idea. “You know what, I’ve just spent the better part of a decade working on this book. I can’t begin to think of a next book.” But she cracks jokes about future topics. “Let’s see, I’ve written about plants and now I’ve written about animals, so that leaves, what, minerals? I’ve got to round out my repertoire.”

The real answer is that Orlean is looking forward to taking some time off—not that she won’t have her hands full. Orlean will continue writing for The New Yorker; in the latest issue, she profiles fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier. She also has a young son and that ever-increasing menagerie of animals back home in New York, proof positive of her nearly boundless curiosity. At last count: One dog, three cats, two fish, two ducks, four turkeys, eight chickens, three guinea fowl, and 12 Black Angus cattle.

“Well,” Orlean adds upon taking stock of this impressive roster, “there may be some geese soon, too.”