Every great literary tradition has its progenitor. The Romantics had Goethe. The Modernists had Hegel. And for the vast canon of works devoted to the modern gal’s sexual escapades and shoe-shopping habits, including Candace Bushnell’s Sex and the City and Cecily von Zigesar’s Gossip Girl, we have Francine Pascal to thank.

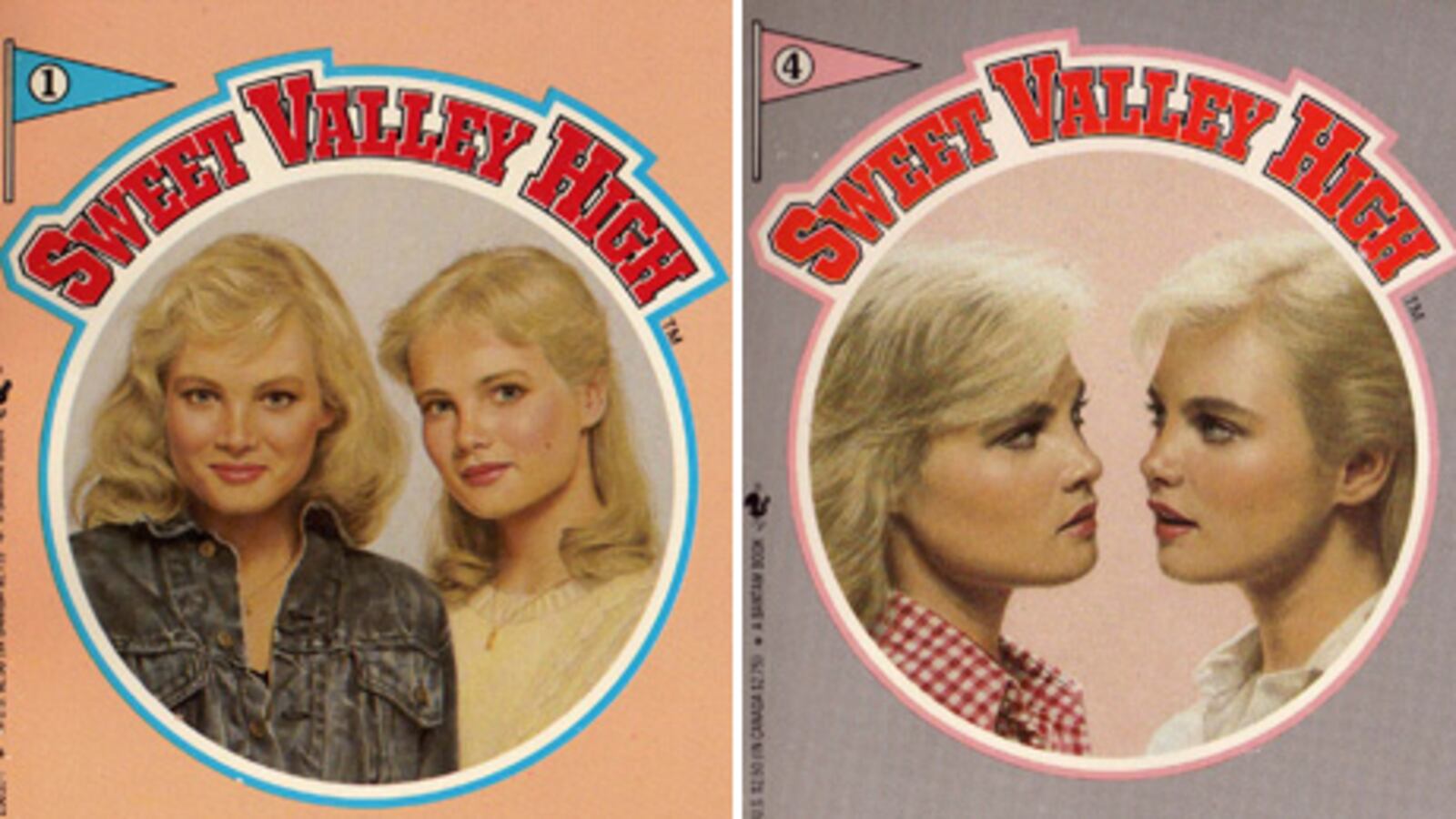

Pascal gave us Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefield, the pert, blond, miniskirted stars of Sweet Valley High, which burned up bestseller lists in the 1980s—the first teen fiction to appear on The New York Times paperback bestsellers list, alongside John Updike and Norman Mailer. Pretty, popular, with perfect California tans, the identical twins were the Carrie Bradshaws of their day—"the most adorable, dazzling 16-year-old girls imaginable," as Pascal once described them—wearing the best clothes, dating the most popular guys, and always on the verge of losing their virginity... but somehow remaining chaste.

It all sounds terribly quaint today, with Snooki caterwauling around the Jersey Shore and high schoolers shagging on MTV. But, perhaps from nostalgia for simpler times, the Sweet Valley is hot again. The novels were updated and re-released two years ago. Juno writer Diablo Cody is working on a feature film about the blue-eyed queen bees. And against the cultural currents, Pascal, now 73, is back with Sweet Valley Confidential, the first new book in seven years.

Sweet Valley Confidential picks up a decade after Sweet Valley High left off. The once-inseparable sisters—mild-mannered Elizabeth, juxtaposed against the flirty, manipulative Jessica—are no longer students at Sweet Valley High, but grown up, and with adult problems like divorce, abusive husbands, and stolen lovers. Now 27, the girls are estranged—Jessica is living with her fiancé in the impeccably glossy Sweet Valley, California, while Elizabeth is on her own in a shoebox-size Manhattan apartment, working as a writer. The girls still look identical, down to the parts in their shoulder-length blond hair. The same themes are there, too—friendship, tension, boys, sex. But the gals have matured, or at least changed with the times: They now actually have sex and use Facebook.

Pascal may be three times her characters’ age, but the beloved writer believes she’s got her finger on the pulse. (One editor says the arrival of her book’s manuscript caused a flurry of “squealing women” in the office.) From her fifth-floor apartment in midtown Manhattan, she carefully pages through a stack of hand-typed manuscripts, and the book’s original pitch letter, to Bantam Books, in 1982. There is also something called the Sweet Valley “Bible”—a thick guide to all things Jessica and Elizabeth, down to the color of Jess’ legwarmers to just how conniving she could be (the answer: “very”). Readers may be surprised to learn that Sweet Valley Confidential is the first Sweet Valley book Pascal has actually written cover to cover (though, she says with a laugh, “I wrote every single one of those f--king plotlines”). Although her name was featured on each cover as “creator,” she hired a team of ghostwriters to turn her outlines into chapters, while she could work on more “serious” subject matter. “There were times I didn’t want to be defined by this,” says the mother of three, who has written a number of adult novels, but never with the same commercial success. “Little did I know, this would be my career, the thing I'd be remembered for.”

Ironically, Pascal had never set foot in California when she birthed her Valley dolls. A lifelong New Yorker, she grew up in a Jewish family in Queens, inspired by her brother, the playwright behind Broadway hits Hello, Dolly! and Bye Bye Birdy. After a stint writing for soap operas with her husband, a columnist for Newsday, Pascal conceived of Sweet Valley as a kind of teenage Dallas. “I got my images from MGM movies,” she laughs. “But since I’d never been there, I could do whatever I wanted.”

That, of course, made the fantasy of Sweet Valley even greater—a sun-drenched utopia where everybody drove convertibles and hung out at the shake shack after school. And while Pascal is the first to admit that Jessica and Elizabeth were shallow—“Dan and I used to fall on the floor laughing about how silly they were,” she says, referring to her friend and publisher at St. Martin’s, Dan Weiss—they were powerful protagonists, too. Pascal’s books may have centered on boys and bras, but they tackled issues like date rape, drugs, and divorce. In Sweet Valley Confidential, a prominent figure comes out as gay. “There were many superficial things about them, but when it came right down to it, readers were getting my politics, my ethics, my morals,” Pascal says. “And I wanted these girls to drive the action.”

Sweet Valley has always been about creating an illusion—girls that were just a little too perfect, a little too rich, with flawless complexions and perfectly straight teeth (no braces or Clearasil here).

In the beginning, that wasn’t enough for many booksellers, who deemed Sweet Valley too “commercial” for their readers. The Times snubbed the series; librarians fought to keep their stacks free of the “skimpy-looking paperbacks,” as one library journal put it. It was Pascal’s fans who defended her: buying a dizzying 250 million copies before the series published its 152nd and final title, in 2003. The series even became a case study on how to get young girls to read. “Sweet Valley changed the dynamics of the industry,” says Barbara Marcus, who, as former president of Scholastic’s children’s business, published The Babysitter’s Club, Goosebumps, and Harry Potter. Sweet Valley spawned seven spinoff series, a TV show, a board game, and dolls. Not until Twilight came along have girl fans been so loyal.

The question, of course, is whether they will still be. Ultimately, Sweet Valley has always been about creating an illusion—girls that were just a little too perfect, a little too rich, with flawless complexions and perfectly straight teeth (no braces or Clearasil here). That was the allure. But for original fans, now in their thirties, there’s the threat that those same storylines may be too quaint for modern day. Sweet Valley was revolutionary—but as Pascal knows all too well, teen dreams never look as glossy as the light of day.