Most of the time, being a survivor of sexual assault doesn’t make you feel “brave” or “inspiring” or “strong.” People keep using those words. But most of the time it just makes you feel powerless and confused and crazy—at least for me anyway.

I was sexually assaulted when I was a child. I spent my first journalism internship getting routinely harassed and watching other, more powerful women get routinely harassed.

When I was a local crime reporter, I was sexually assaulted by a man whom I met in a courthouse while working on a story. Later, the judge who was presiding over that case retired amid a probe into his own sexual misconduct.

I walk to the office every day between and around men on the subway and on the street who may—at any moment—grope or harass or flash me. Some of them do.

When I open my email or check my Twitter I get messages from too many well-meaning men hitting on me or encouraging me in ways that can feel creepy or exploitative.

Those of us who report on crime and sexual assault know that it’s pervasive—of course it is.

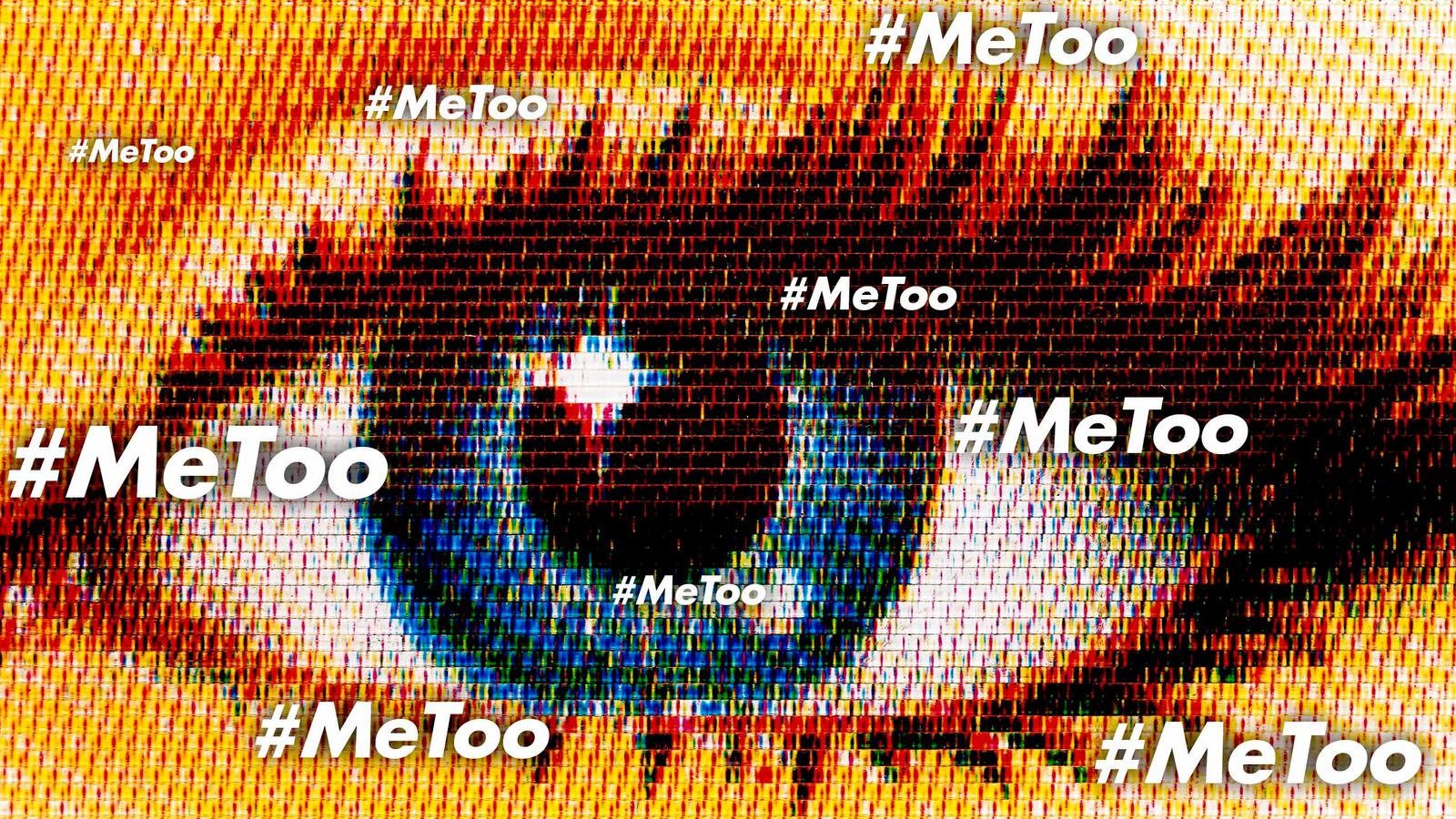

In the days since the allegations about Harvey Weinstein broke, the #MeToo campaign has transformed every corner of social media into a veritable ocean of sexual assault and harassment stories. I’d like to say that I feel solidarity and compassion, but I mostly just feel like I’m drowning in this inescapable trauma.

It sounds silly for a writer who specializes in cases of sexual assault, but before this week I got to—for the most part—walk around pretending that maybe once I was old enough (or powerful enough or rich enough or respected enough) I’d get to be finally, finally protected from this unbelievable deluge. It was a nice bubble, to be honest.

This week has instead provided a profound confirmation that no woman in Hollywood, journalism, politics—or anywhere, really—is immune.

I secretly hoped someone, anyone was.

Maybe it really does require the horror of every woman I know swimming in her own trauma on social media so you can all see it. Maybe it’s worth it. Maybe it isn’t.

The bottom line is: We shouldn’t have had to do this in the first place. And beyond catharsis, I’m worried that #MeToo won’t heal the pain.

As my friend Shannon Palus, a science reporter, asked on Twitter this week: “Anecdotes weren’t enough, data wasn’t enough, witnesses weren’t enough, each individual person had to register their complaints in public for all of this to—I hope, I hope—be believed? Really?”

In the right way and the right time, sharing your own story can be empowering. About a year ago, I found it cathartic.

“Telling our stories can help,” wrote Jessica Valenti. “It can help victims not feel quite so alone and make others understand the breadth and depth of the problem.”

If you’re ready and you’re sure and you’re willing, then please do tell your story. It can do so much. It can prevent other assaults and it can expose hypocrites and it can honest-to-God save children from the same fate.

But I can also tell you from experience that it hurts, and I think we don’t want to admit that sometimes it doesn’t help.

It might just make you feel vulnerable, and you might just be handing other people a really sharp knife they can use against you. Truthfully, no one can protect you from that once you’ve shared your story online.

And the pressure to disclose can be oppressive.

“You should disclose if you want,” one friend wrote on Facebook. “Perhaps it will lead to more healing or to more solidarity. Perhaps it will not. The burden of this however does not belong to you. You can set it down.”

So if you need to: Please set it down. Don’t carry it.

I went public with my story last year and I still spent part of this week trying to discern for myself whether I’m a fraud because I didn’t fight back harder during my second sexual assault. I understand how that sounds. All I can tell you is that’s how I feel.

“I’m in total awe of the women who’ve come forward and I even feel part of the mass catharsis,” one friend told me today. “But there’s also a light edge of guilt (and then annoyance for feeling guilty) for not joining in the cause—which is nuts.”

Watching trauma go viral, she said, feels both “heartening” and “flattening.”

One friend said she didn’t share her own violent sexual assault experience this week because she wasn’t sure if it was a good enough story to be counted.

“I’m not entirely sure if I’ve even pieced together what this all means to me or how it’s changed me,” she said this morning. “It still makes me feel powerless thinking about it. I don’t like feeling like I am a victim again.”

Others don’t share because they don’t want to have to. Or because trauma is deeply personal. Or because they haven’t processed it themselves. Or because their perpetrators were family members they still have to talk to.

A fellow reporter said that, at the age of 50, she is still too afraid to even accidentally—or via implication—out her perpetrators by coming forward.

“One of the worst offenders of my personal experience is still out there and still relevant in my world,” she said. “I am too afraid of what he could do to me or my career.”

“The truth is,” Jessica Valenti continued, “that nothing will really change in a lasting way until the social consequences for men are too great for them to risk hurting us.”

In any case, the onus to impose those social consequences isn’t on you. You don’t owe anyone anything—and you especially don’t owe them your story.