Bashar Mahmoud Kabisho was almost 20 when he learned that Syria’s next leader would share his first name. It was January of 1994. An aging Hafez al-Assad was the country’s strongman at the time, and Bassel, his eldest son, was being groomed to take his place. But when Bassel died in a car crash, flipping his Mercedes as he sped down the highway through a heavy fog, the spotlight moved to his lesser-known younger brother, Bashar, who was off training as an ophthalmologist in London at the time.

When Bashar al-Assad became president in 2000, he enjoyed a good measure of popularity. The young leader offered Syrians some hope, promising reform of the country’s suffocating police state. Kabisho took newfound pride in his name. “When Bashar became president, I felt a little arrogant, because everyone was saying, ‘We love you, Bashar,’” Kabisho says. “At the time, I didn’t know Bashar was going to be a criminal. I was happy.”

In Arabic, the name Bashar means messenger who brings good news. It has long been popular in the region even without any political help, notes Adel Iskandar, a professor of Arabic studies at Georgetown University. (Iskandar adds that a popular 1980s cartoon “featuring an enterprising bee named Bashar” gave it a further push.) Many Syrians say the name enjoyed another popularity surge once Bashar al-Assad took center stage, as baby boys started to get the president as their namesake.

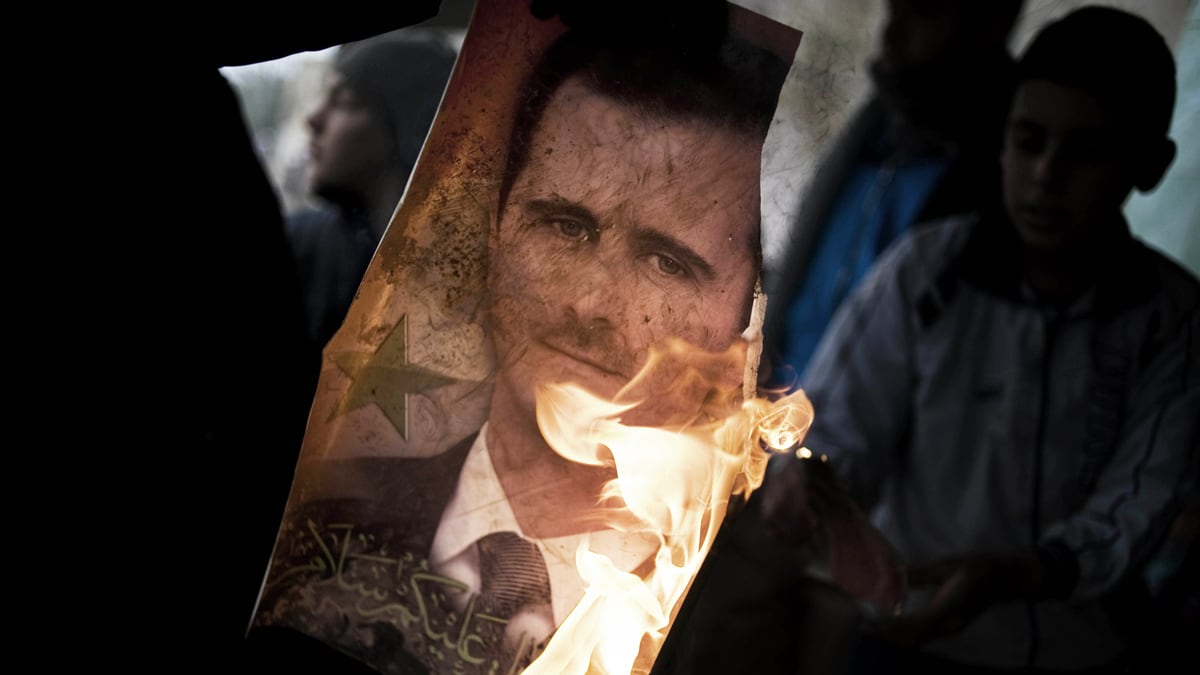

Now the name Bashar, as Assad is often called, is commonly heard alongside words such as “dog” and “thief.” His regime is in the midst of an 18-month-old crackdown that has made Syria’s revolution the bloodiest by far of the Arab Spring. There have been some 26,000 deaths in the conflict so far, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. The United Nations estimates that more than 235,000 Syrians have been made refugees, while another 1.2 million are internally displaced.

As the violence mounts, the name “Bashar” seems to be rapidly losing its appeal. And some Bashars are even changing their names.

“People don't want to be called Bashar anymore,” says Nasr Adin Ahmah, a veteran Syrian activist. “There’s a sense of shame attached to the name. It’s sort of like calling someone Osama in America.”

Mohamed, a man from Aleppo who asked to withhold his family name, was Bashar until he announced his name change by way of a Facebook post. A student at Aleppo University, he was a regular participant at anti-regime protests, and he remembers numerous uncomfortable moments arising on account of his name. “My friends would say, ‘Go away, Bashar!’ And then they would look at me: ‘But not you. You can stay,’” Mohamed says. “Finally I told everyone to just call me Mohamed. I’m not Bashar anymore.”

In Egypt, protesters chanted against Mubarak, and the name to be reviled in Libya was Gaddafi. But in Syria, Bashar seems to get just as much attention as Assad, if not even more. “Bye bye Gaddafi. Bashar, your turn is coming,” Reuters reported Syrian protesters chanting after Muammar Gaddafi fell.

Bashar features prominently in many revolutionary slogans—“The people want to hang you, Bashar,” was the tag one man who used to spray anti-regime graffiti picked recently when asked to name his favorite. (He has since graduated from graffiti to smuggling weapons and making bombs.) The anthem of the protest movement was largely considered to be a song titled “Come on Bashar, Leave.” The refrain is: “Hey Bashar, hey liar. Damn you and your speech, freedom is right at the door. So come on, Bashar, leave.’

One Syrian refugee now living in the Turkish city of Antakya recalls teasing her teenaged cousin about his name before she left home. He was called Bashar in honor of Assad, who was in power by the time he was born. Now the boy is fervently against the regime, recalls the woman, Medya, who asked that her family name not be used—and he is angry at his parents, too. One incident in particular brought the embarrassment to a head.

At a demonstration, his brother called out to get his attention with a message that was the opposite of what everyone in the crowd was there to say: “Bashar, come here!”

People turned and stared. Eventually the boy’s mind was made up. “He told us: “Please don’t call me Bashar,” Medya says.

The boy now goes by Mezgin—a Kurdish version of the name—instead.

Miral Biroreda, a Syrian activist of Kurdish descent, says Mezgin’s parents may have had their reasons for choosing to name their son Bashar. A name like that might ease some of the pressure of living under such a stifling state. Syria’s Kurds have traditionally been especially repressed, and Biroreda recalls how those with distinctively Kurdish names like his often were refused identity cards in the past.

Growing up, he says, he noticed that the Kurdish kids with regular Arabic names even seemed to have an easier time. “When I was a kid, I had so many problems with my name,” Biroreda says. “So maybe [Mezgin’s] family preferred to call him something the regime would like.”

The desire to make things easier with the regime might have been part of the rationale behind naming many of Syria’s Bashars, Ahmah, the activist, says—along with those named Bassel or Hafez. “It's like naming your child Mohamed,” he says. “It's a holy name. It gets a lot of positive attention.”

As the conflict grinds on and tensions rise, meanwhile, it’s not just names affiliated with the ruling family that are coming under increasing scrutiny. Assad hails from the Alawite sect of Shiite Islam, a minority in predominately Sunni Syria, and Alawites dominate the regime. Reuters has reported that many Alawites in Syria are working to hide their accents, and even their names—such as Ali, the name of the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohamed whom Alawites regard as divine. “These days I am scared to give my name,” a student from a Sunni suburb named Ali says in the Reuters report. “Sometimes I say it is Omar. Sometimes I use something else.”

Iskandar, of Georgetown University, points out that names can be a point of tension throughout the Middle East. For example, “a similar problem with names is becoming palpable in Egypt with names suggesting Christianity versus Islam,” he says. “So there is a lot in a name.”

Kabisho, who was so proud of his name when Assad came to power, has decided to make the most of it now. When the revolution began, he coordinated medical aid in the Syrian city of Idlib, and he continues his relief work along the Turkish border today. “I made people like the name by doing good things. Now they say, ‘I want Bashar to come,’” he says. “My name is very great. I would never change it.”