Taylor Swift has been extremely consistent about this political opinion: She hates Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN).

That much was clear in 2018, when Taylor Swift issued her first political endorsement for Blackburn’s then-opponent for the Tennessee Senate seat, Democrat Phil Bredesen. And it was made even more explicit in the 2020 documentary Miss Americana, where Swift can be seen seething over Blackburn.

“If I get bad press for saying, ‘Don’t put a homophobic racist in office,’ then I get bad press for that. I really don’t care,” Swift told her publicist in one scene. “I think it is so frilly and spineless of me to stand onstage and go ‘Happy Pride Month, you guys,’ and then not say this, when someone’s literally coming for their neck.”

But apparently, the megastar’s own record label and publisher, Universal Music Group, feels differently—so differently, in fact, that UMG’s political action committee isn’t just maxing out the allowable contribution to Blackburn; it’s exceeding the limits.

On Sunday, federal regulators put UMG’s PAC on notice, flagging the group for giving Blackburn more than the legal limit allowed in an election.

More than just a clerical error, however, the notice shines a light on UMG’s long-running financial support for the Tennessee Republican, an arch-conservative that Swift has taken on as a personal political adversary, blasting her as a “homophobic racist” and “Trump in a wig.”

“Her voting record in Congress appalls and terrifies me,” Swift wrote in an open letter against Blackburn’s 2018 Senate bid, hitting the then-congresswoman for voting against equal pay for women and the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act.

“She believes businesses have a right to refuse service to gay couples. She also believes they should not have the right to marry,” Swift wrote in the letter.

“These are not MY Tennessee values,” she added, endorsing Blackburn’s opponent for her first public political act.

But UMG was on the other side of that fight, bankrolling the Republican as it had for years. The label then signed Swift just weeks after Blackburn won the election.

Federal filings show that UMG’s PAC has put money into Blackburn’s campaigns nearly every year since 2005, shelling out a total of more than $32,000 in political support. And Blackburn has so far raised $9,500 from the UMG PAC to put towards her 2024 bid, nearly hitting its ceiling three years out from the election.

The Federal Election Commission flagged that the latest UMG donation put the PAC over the donation limit for the 2024 primary election cycle. And while the Blackburn campaign appears to have already reallocated the funds to comply with regulations, the PAC has so far failed to do so in its reports.

Blackburn, a Nashville-area denizen who sits on the Senate Subcommittee on Communications, Media, and Broadband, boasts one of the most far-right voting records in the Senate. But Blackburn has burnished a reputation as a champion for the music industry, receiving financial backing from trade and lobbying groups such as the Recording Industry Association of America.

Her voice is so valuable to Music City moguls that in 2014, the head of the Nashville Songwriters Association International told the Tennessean that if the avowed right-winger, at the time a U.S. Representative, were to leave Congress, it would hit him like a death in the family.

“I’d hang a black wreath on our office and close it for a week,” he said.

Still, UMG’s donations stand in sharp contrast to the PACs belonging to the two other major record labels—Sony and Warner—neither of which gave to Blackburn last year, according to FEC data.

Warner’s PAC has only donated once to Blackburn in recent years, in May 2018; the Sony PAC appears to have never given her money, according to an analysis of FEC filings.

Corporate PACs are often employee-funded, but executives and lobbyists tend to make up a disproportionate amount of those donations. The UMG PAC is no different. And it has drawn significant funding from two executives especially close to Swift.

In an early 2020 press release announcing her global publishing agreement with UMG—Swift, a vocal proponent of LGBTQ and women’s rights—said she was “proud” to continue working with UMG head of publishing Jody Gerson, the “first woman to run a major music publishing company.”

“Jody is an advocate for women’s empowerment and one of the most-respected and accomplished industry leaders,” Swift said in the release.

She also praised longtime collaborator Troy Tomlinson, another UMG publishing exec, as a “passionate torchbearer for songwriters.”

Gerson and Tomlinson each gave thousands of dollars to the PAC last year, in recurring donations starting in January, according to federal data.

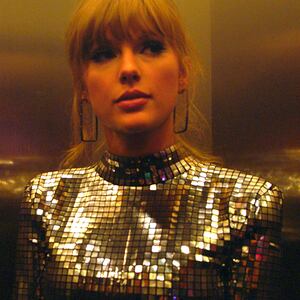

Swift, whose publicist declined to comment for this article, has made no secret of her disdain for Blackburn. Her decision in 2018 to break her political silence and speak out against the MAGA acolyte appears to have spurred a surge in voter registration, and was featured prominently in Miss Americana.

However, the documentary did not highlight that Swift was taking on another major industry player in Blackburn.

The senator reacted to the Miss Americana documentary by praising Swift’s “exceptional” musical gifts, as well as her artist advocacy—an area where the two women would appear to have common ground. Both have backed musicians’ rights, with Blackburn co-sponsoring major pieces of legislation supported by artists, including the Music Modernization Act, which in 2018 passed Congress unanimously and was signed into law by then-President Trump. (Swift nemesis Kanye West got in on the signing fanfare.)

The bill made it easier to collect digital royalties and was hailed as a major step forward by musicians, labels, and publishers alike.

Swift has famously fought these battles herself, leveraging her staggering popularity to challenge industry kingpins directly. After losing the rights to the “master” recordings of her first six albums—before she came under Universal—she embarked on a project to reclaim ownership by re-recording them herself. At the same time, however, UMG was revamping its contracts to restrict their artists from profiting the same way.

But this July, Blackburn appeared to jab at Swift out of nowhere for “trying to change country music” by making it “woke,” issuing an absurd warning that a “socialistic” government would make the 11-time Grammy winner its “first victim.”

“Taylor Swift came after me in my 2018 campaign,” she told Breitbart at the time. “But Taylor Swift would be the first victim of that because when you look at Marxist, socialistic societies, they do not allow women to dress or sing or be onstage or to entertain or the type [of] music she would have.”

Asked for comment about the donations, a UMG spokesperson provided a statement praising Blackburn’s work on behalf of the industry.

“Senator Blackburn represents a vital music community and has a long track record of advocating for issues supportive of creators, including her key leadership on the Music Modernization Act and her service as a Chair of the Congressional Songwriters Caucus. She has garnered broad support from across the music community—including from virtually every leading music PAC. She has received support from the UMG Employee Action Fund since 2005,” the statement read.

“However, none of that excuses, or should be seen as condoning in any way, Senator Blackburn’s derisive comments last summer about Taylor Swift,” the spokesperson wrote.

Two months after Blackburn made those comments, UMG reported its $5,000 donation.