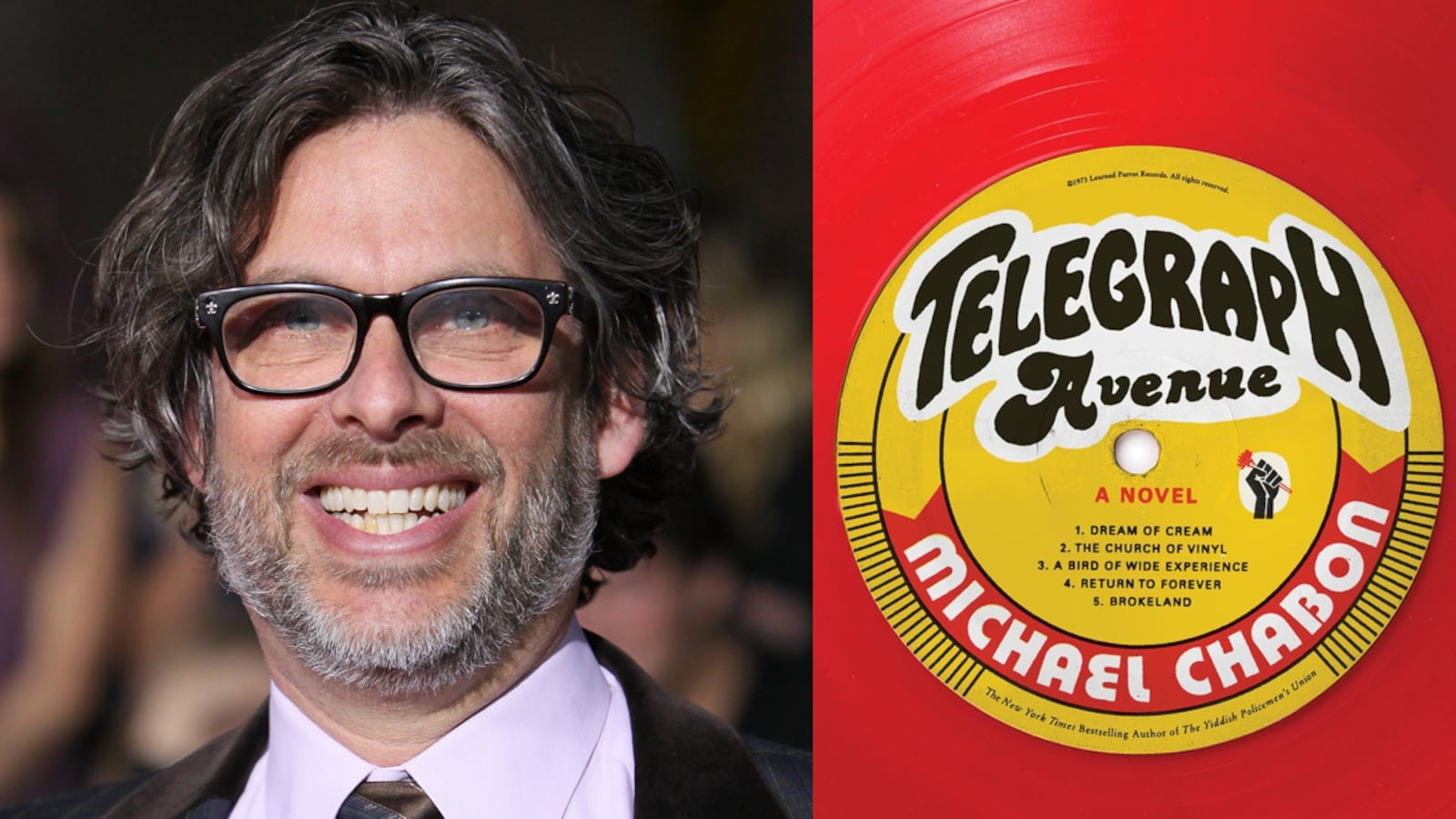

Michael Chabon is a poet of fandom. His characters worship at culture’s niches, such as the comic-books-obsessed duo Joe and Sam who star in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. Other times Chabon’s own love for a genre animates his work; The Yiddish Policemen’s Union is in part an ode to Raymond Chandler. His exuberant new novel, Telegraph Avenue, has at its center one of those temples of geeky obsession and eternal bullshitting: a vintage-record store, in this case one specializing in jazz and set in a neighborhood the characters call Brokeland, "the ragged fault line where the urban plates of Berkeley and Oakland subducted." Superheroes, magic, cartography, baseball, sci-fi, detective fiction—Chabon’s enthusiasms are many. But a problem he encountered early on while writing Telegraph Avenue was that jazz wasn’t one of them.

“I love jazz, but it never lit that obsessive fannish fire under me,” Chabon said over the phone from his house in Maine, where he spends the summer with his family. This was a particularly troubling problem because the novel’s quirky cast of midwives, musicians, and whale-rights lawyers all orbit around the used-jazz-record store. “A church of vinyl,” one character calls it, while explaining why they’re hosting a former patron’s funeral there.

“They needed to be obsessive, and I just wasn’t feeling it,” Chabon said. Fortunately, while perusing a bookstore in North Carolina, he stumbled across a magazine called Wax Poetics. It was dedicated to soul jazz from the ‘60s and ‘70s. “It was a magazine for obsessives.”

“All I need is a world and I can get obsessed,” Chabon said. “All of a sudden I had my music for my guys.” His guys are Archy, an African-American bassist who returned from the Gulf, who meets Nat, a white aficionado of vinyl. The pair stay up until 5 a.m. smoking joints and listening to soul jazz. Years later, they’re selling it in their store and playing it in their band.

This is a classic Chabon scenario: two young men go from wary strangers to bosom buddies as soon as they hit upon a shared infatuation. In Wonder Boys, the aspiring novelist Grady Tripp and the aspiring editor Terry Crabtree become friends and professional partners because they both love a neglected horror writer. In Kavalier and Clay, the cousins Joseph Kavalier and Sam Clay are thrown together when they discover comic books, and they go on to dominate the medium.

Chabon got the idea for the novel when he walked into a used-record store in Oakland, one that sadly is no longer there, and saw customers, black and white, hanging out and talking about records. The two owners—one black and one white—held court. “It chimed with me because it was like some tiny little microcosmic replica of the place where I had grown up—Columbia, Maryland, which is now a nice but unremarkable suburb. But at the time I lived there was a planned community with very utopian, integrated aspirations,” Chabon said. The store “was a tiny version created by people who were willing themselves to come together and share a common passion.” He’d been working on a TNT pilot about two midwives who run into trouble when a birth goes awry, so he married his midwives to his record-store owners and went from there. The show never happened, but he couldn’t forget the scene, and five years ago decided to turn it into a novel.

In Telegraph Avenue, Archy and Nat’s microcosm is under intense strain. A media megastore is preparing to open nearby, and its owner, former NFL star Gibson Goode, is trying to woo Archie away with promises of a stable job and health insurance—bait that looks all the more attractive to Archy with a new kid on the way. Meanwhile, his midwife spouse, Gwen, who has walked out over an infidelity, is facing a ban from the local hospital after a birth went badly, putting pressure on her partnership with Nat’s wife, Aviva.

The adult relationships buckle, but a fresh one is forming between Nat’s acknowledged son, Julius, and Archy’s unacknowledged son, Titus, who has recently appeared in Berkeley. They meet in a class on Quentin Tarantino and spend the summer binge-watching blaxploitation movies. Julius nurses an intense and ambiguously unrequited crush on Titus.

Blaxploitation is not only the object of Julius and Titus’ fandom—it’s also constantly bleeding into the plot. Archy’s deadbeat dad is a fallen blaxploitation star who returns to Berkeley so he can blackmail a city councilman-cum-mortician over a murder committed in their Black Panther past, thus setting in motion a slapstick subplot involving washed-up kung fu fighters and incompetent henchmen. The blackmail sublot comes from Chinese martial-arts fiction, called wuxia, which Chabon read in preparation for the novel. Wuxia stories are typically about sorting out the consequences of some crime committed in the prior generation. “When I realized that, it lit a lightbulb over my head.”

Blaxploitation serves another, non-nostalgic purpose as well. “As a white writer writing a book with a lot of black characters, I felt like blaxploitation gave me a very clear way to signal that I know there are ambiguities and pitfalls involved in what I’m doing,” Chabon explained. As Archy’s wife points out in the novel, blaxploitation is a “bastard art form,” mostly written by white writers and directed by white directors. “It gets into the territory where things get tangled, and that’s where things get interesting as well,” Chabon said.

The blaxploitation, martial arts, and retro soundtrack all give Telegraph a Tarantino vibe, if Tarantino were more earnest and interested in the logistics of midwifery. In case you miss it, Titus and Julius meet in a class on sampling and allusion in Kill Bill. Chabon, though as referential as Pynchon, has never been one to code his allusions; he flies them proudly. Tarantino feels especially present in the dialogue. Eccentric musicians draw Talmudic distinctions between obscure recordings. Others pontificate on varieties of donuts. “Bear claw is my, what you call, control,” muses a guy on a stakeout, before explaining that bear claws, because of their general awfulness, are the best measure of a donut shop’s quality. “You want to see how much love and affection the chef put into the bear claw. If the bear claw’s good, the standardize donuts be even better.” It’s the comedy of gravely debating topics of vaporous importance—how long you can keep it going with a straight face?

Chabon finds the comparison to Tarantino's dialogue flattering. “I think he’s fantastic,” he said, but insists the similarity probably has to do with a common ancestor. “When I was learning to write dialogue back in The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, I was learning by reading Elmore Leonard,” and Tarantino was also inspired by the Dickens of Detroit. The preoccupation with martial arts, though, is very much Tarantino. Back in the early 2000s, Chabon was commissioned to write a script for a Hong Kong martial-arts movie based on Snow White. “That was when I really plunged into the whole world of 36 chambers and all that, but it was post-Tarantino, so I saw them through a Tarantinoesque lens.”

Other influences are more obvious. There’s Raymond Chandler, more palpable in Telegraph Avenue’s plentiful and surprising similes than in any of Chabon’s other work save The Yiddish Policemen’s Union. Luther drives a “crocodile green” Oldsmobile Toronado, “Its chrome grin stretched beguilingly and wide as the western horizon.” By the time he reappears, it’s “bleached to a glaucous white, rusted in long streaks and patches so that the side visible resembled a strip of rancid bacon.” Elsewhere, the feathers of a parrot one of the record-store regulars carries on his shoulder is described as having a “hot newspaper funk.” (Chabon is pretty much peerless when it comes to nailing descriptions of smells.) A motion-sick assistant on Goode’s zeppelin is “holding himself like a plateful of water.”

“I’m frequently working in this mode, blending high and low diction, literary language and slang, vivid lyric imagery with street speech, going from high to low in a single sentence,” Chabon said. “Chandler was one of the first writers that gave me a clue how to do that.” Speaking like a true fan, Chabon calls Telegraph Avenue “an integrated hybrid of all the books I like to read.” Those influences were present in his past works as well, but they all came together here. “In many ways, I think of it as a hub of a wheel, and all my other books are spokes of the wheel. Not that it’s a culmination, but all the previous concerns of my books flowed together to help me shape the story.”