When Barack Obama took office in January 2009, white supremacists were fragmented and without charismatic leaders. That quickly changed with the arrival of Richard Spencer, Matt Heimbach and Milo Yiannopoulos, a generation of new leaders who created and captured a following that capitalized on white unease over a black president.

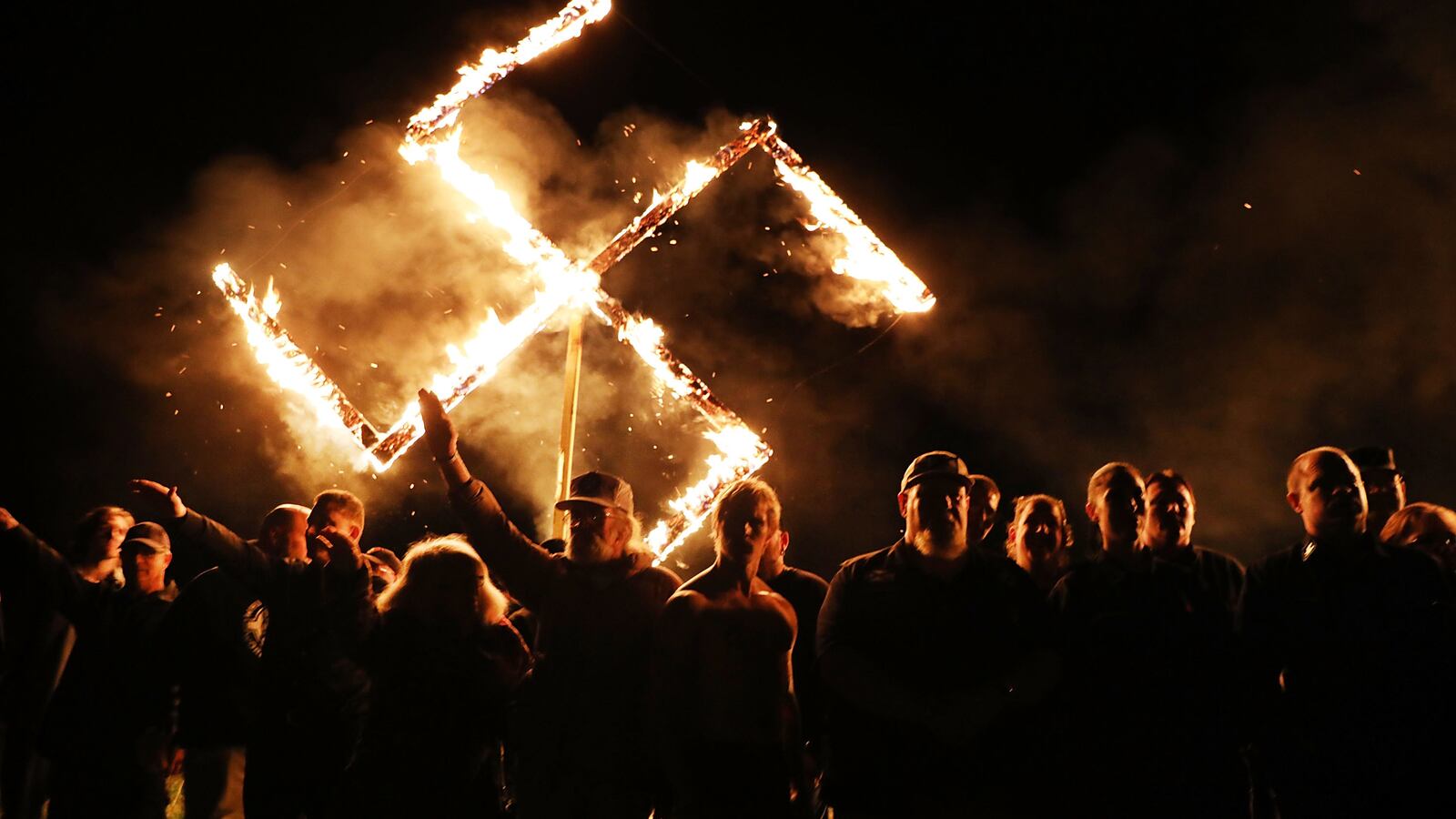

The good news is that over time these leaders were marginalized and neutralized, finally demonized by the media and subjected to public humiliation for their neo-Nazi views. They were disrupted. But the sentiments they embraced had taken hold, bursting into full view in Charlottesville in 2017, with white supremacists carrying torches and chanting, “Jews won’t replace us.”

They’re fragmented again post-Charlottesville, and post-El Paso, seeking other social media platforms while law enforcement plays whack-a-mole, beating them back until they pop up somewhere else. The American people are left to wonder what more can be done to counter this growing threat that government has left unattended for too long, while keeping quiet what information it has collected, including a document showing that white supremacists were responsible for all race-based domestic terrorism incidents in 2018.

“There is no government monitoring of social media anymore,” says Daryl Johnson, a former intelligence analyst at the Department of Homeland Security. He wrote the 2009 report documenting the rise of domestic terrorism fueled by white supremacists in a growing online community. Yet because of First Amendment concerns, law enforcement can monitor social media only when tipped off to a specific threat.

When Congress returns in September, Democrats plan to summon national security officials and question them about the administration’s plan, if any, to address the growing threat—and about President Trump’s role in fueling the phenomenon.

After conservative media leaked Johnson’s report, spurring a backlash that squelched its findings, white supremacists had a decade of unimpeded growth. Their adherents now number in the hundreds of thousands, and the body count has gown. “It’s the same weapons but people are getting more proficient at carrying out the attacks,” Johnson told the Daily Beast in an interview where he called President Trump’s initial admission that the El Paso attack constituted terrorism “a glimmer of hope.”

“There’s so much stuff we can be doing but it all starts with acknowledging there’s a problem,” says Johnson. “It’s not a crazed gunman, or a mass shooter, or a hate crime. A hate crime is a personal vendetta. When you go to a shopping center and shoot up a bunch of people because you’re upset about immigration, that’s terrorism. And once you start calling it terrorism, we can start gathering data and devoting resources and developing strategies.”

Domestic terrorism inspired by white nationalists should be taken as seriously as ISIS-inspired terrorism inspired by Muslim extremism—a major leap in thinking in an administration reliant on the votes of an aggrieved white male population inspired by white supremacist beliefs. “There’s a glimmer of hope that they’re beginning to do the right thing, but it will take years for the government to catch up and actually start decreasing this,” says Johnson.

The investigation that Johnson launched in January 2007 and dubbed “Gathering Storm,” originated with an RFI (request for information) from the U.S. Capitol Police. There was a black senator from Illinois announcing his run for president. Could Homeland Security monitor right-wing web sites and white supremacist sites to see if there were any threats to Obama?

These kinds of requests and information sharing had become commonplace after 9/11, and Johnson’s unit at Homeland Security initially found no threats on the sites they monitored. But they didn’t end the investigation. “I told my analysts, what if he does become president and what might that do to the threat level? Not only is he black, he’s a Democrat.”

They collected data from web sites, police reports, civil rights groups, and they kept “Gathering Storm” as an open investigation throughout the 2008 campaign. Once Obama won the election, Johnson had an outline and, in his words, started putting pen to paper.

The report he authored described the growth of “right-wing extremist activity, specifically the white supremacist and militia movements.” It said that the Great Recession unfolding at the time could help recruitment into these movements, and that internet platforms would allow domestic extremists to radicalize others just as foreign groups like the Islamic State had done. The report warned that returning Iraq War veterans were susceptible to being recruited.

The report was meant for law enforcement, not for public consumption, and when right-wing media leaked it out, there was a firestorm. The right felt unfairly tarred, with Fox News, Rush Limbaugh and Pat Robertson leading the charge. The left had First Amendment concerns about the monitoring of websites.

Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano rescinded the report, bowing to congressional pressure led by then Kansas Rep. Mike Pompeo, who said focusing on domestic terrorism smacked of political correctness and distracted from the real threat of Islamic terrorism. The American Legion was incensed by the prediction that returning veterans could be recruited to these growing movements.

Napolitano was new to the job, arriving in Washington at the end of January 2009. She was Johnson’s third Homeland Secretary, after Bush appointees Tom Ridge and Michael Chertoff. “She was the first secretary to show interest in domestic, right-wing terrorism,” he says. “All the others cared about was preventing another 9/11.”

Napolitano had been Attorney General in Arizona, a state with a large militia presence. She led a portion of the criminal prosecution against Army veteran and anti-government activist Timothy McVeigh for the Oklahoma City bombing of a government building in 1995 that killed 168 people, including 19 children in a day care center housed at the facility.

She was familiar with anti-government hate groups. “She asked us three questions,” says Johnson. “Is there a rise in right wing terrorism? Is it because we have a black president and other factors? And what should we do about it?”

After the election, Johnson’s unit at Homeland Security monitored Stormfront.org, the largest gathering place for white supremacists. The day after the election the site, which typically got 30 to 40 people a day, soared to over 2000 people and every day grew exponentially to reach 300,000 by the time Johnson left government service in 2010. Since then these groups have proliferated along with the number of people identifying themselves as white supremacists—along with sites teaching paramilitary training for people to form their own militias.

The Obama administration was new to Washington and caught off guard with the Republican backlash. Napolitano initially tried to defend the report, but as the political backlash grew, she backed down. “Even if he (Obama) wanted to do something, he would have played into fears of having a black Democrat in office. He would have agitated them and helped them gain strength,” Johnson says. “There was a chilling effect. If you talked about right-wing nationalism, there was a price to pay.”

If opportunities to stymie it were lost during Obama, with Trump in office, right-wing extremism and white nationalism has outright flourished. Trump mainstreamed extremist ideas in the 2016 campaign with the border wall, the Muslim travel ban, and the deportation of immigrants. “Things being talked about on (right-wing) message boards 10 and 15 years ago are now being taken as potential policy,” says Johnson. Islamophobia and even white nationalism are on Trump’s twitter account. “These are code words you see on white nationalist boards all the time, and the president of the United States is playing right into them.”

This is no coincidence, says Johnson. “The Republican Party has adopted a strategy to breed fear and paranoia in order to generate votes to win elections, and that’s exactly what they did with Obama. They created the birther movement.”

Obama prevailed. Will others?

When Trump was asked if white supremacy is a problem, he said no, that it’s only a small number of people. That’s not true, says Johnson. There are hundreds of thousands of people in the United States that embrace white supremacy. They’re trying to instigate a race war. That’s their vision. “Can you imagine if there were two or three hundred thousand ISIS recruits, the threat that would pose? They need to treat them equally.”

Asked what he anticipates next from this administration, Johnson says, “If the past is any reflection of the future, not much is going to be done.” When Trump read his post-El Paso speech where he seemed to acknowledge the threat of domestic terrorism, “it almost seemed he was bored,” Johnson says. Maybe that’s the best we can expect from a president who led the birther movement.