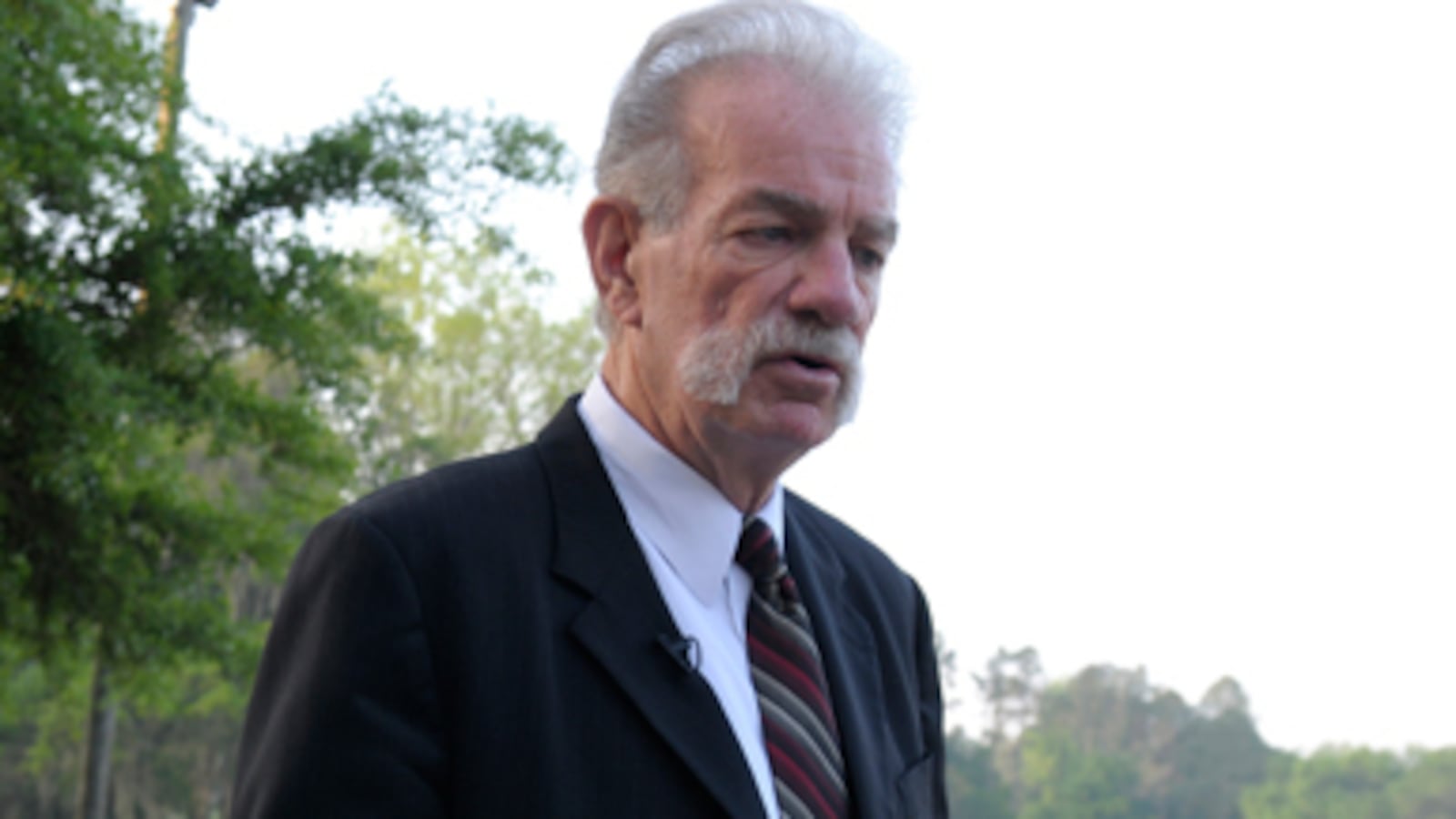

Pastor Terry Jones had just been informed that Jamaat-ud-Dawah, an Islamic organization banned in Pakistan, had issued a fatwa against him. "$2.4 million on my head!" he said, apparently exalted. Is that true? I asked him. ( I have interviewed Jones several times now, and know that a fatwa is the kind of thing he brags about, exaggerates—especially to a print journalist. Later I'll find out that the price on his head is only $2.2 million.) "It is!" he says, promising that Mrs. Sapp, his media-relations person, will "shoot" me all the relevant names and publications, as soon as our interview is over.

Seven months ago, I heard Jones making similar proclamations to the world press, assembled on the raggedy field outside his Gainesville church. Jones, and his congregation of 30, entranced the world media for several news cycles last year with their plan to burn Korans on September 11. But, one day before, to the visible annoyance of many of the reporters on site, he canceled the event. He was not ready to die for it after all, it seemed. Or, as a cable-news cameraman put it to me, "He wasn’t ready for the big time."

Now, apparently, he is. Last week, Jones burned a Koran and broadcast the images over the Internet. Ignored by local media, the footage reached Afghan screens before American ones. The response was horrific: An angry Afghan mob overran the U.N. headquarters, killing seven foreigners and several Afghans, in protest of his blasphemy. The violence seemed especially senseless given the petty motives underlying Jones' provocations. He'd grown despondent over the sudden loss of attention, after the media caravan had moved on from his front lawn. He wanted it back.

After the initial cancellation, Jones flew to New York, hoping to snag a meeting with Feisal Abdul Rauf, the man behind the “ground zero mosque.” But Rauf wasn’t available, and Jones, dressed all in leather, spent much of his day wandering around downtown New York, visiting the towers like any other visitor. By the end of the day, the last television cameras had deserted him.

For months, only shaky YouTube footage offered proof of his continued existence. During this time, Jones made a lot of friends online, members of other Islamophobic organizations such as Act for America. Ahmed Abaza, the California-based owner of The Truth TV, an obscure Coptic television network dedicated to converting the Middle East to Christianity by satellite, invited Jones and his underpastors to offer a weekly address on his station. These new acquaintances helped stoke Jones' ambitions. Maybe it wasn't too late to burn Korans, after all. Perhaps the American media were open to the possibility of a sequel?

“We organized everything to ensure a fair trial,” Jones said.

But there were narrative hindrances. During his day in New York City, in full peace-maker mode, Jones promised Today show host Carl Quintanilla that his church wouldn't burn any Korans, "not now, not never." By the new year, however, Jones had come up with a knockout pitch. The church couldn't burn Korans—but what if it was no longer a church? What if it was, instead, a courtroom, the Koran was on trial, and burning was one of the possible penalties? "The complaints about International Burn a Koran Day was that it was unfair," the pastor told The Daily Beast. "Muslims told us that it was not a book of violence but one of peace. We said, OK: a fair way to discern that would be to put the book on trial. We'd bring charges against it and invite them to defend it."

But the mixture was missing an important element before it could bubble over into the mainstream. "If you want to spread your message, you need the media," Pastor Luke Jones, son of Terry, told me. The congregation started a new website, flashier, with a name catchier than Dove World Outreach Center, but not much: StandUpAmericaNow.org. (During interviews, Jones will sometimes refer to Stand Up America as if it were a separate organization that just happens to cover the happenings in Dove World Outreach.) Jones posted a dramatic YouTube clip, which served as the trailer of the sequel. In a leather jacket, he spoke with the dramatic poise of a WWF champ challenging an opponent: "There are four possibilities! The Koran can be BURNED!… or the Koran can be DROWNED! OR the Koran can be shredded… into little bitty pieces, destroyed, shredded. Or a firing squad! Muslims, we challenge you! Last time y'all had a big mouth. …Submit to us… a defense attorney. Come on that day! March the 20th!"

"That video would be hilarious, if it weren't so sad," said Imam Muhammed Musri, the Floridian "E-mom" who so ably discouraged the pastor from his initial Koran-burning plans. Musri convinced journalists who saw the trailer to drop the story, and proceeded to send out a press release to all major media outlets calling on them to ignore the church's bait.

Next, Musri devoted his time to stopping any Muslims from accepting the pastor's challenge. The church desperately needed a Muslim— anyone to lend their court the appearance of balance.

Jones went as far as to invite Anjem Choudary, a British Muslim and public extremist widely accused of inciting hatred and violence in his home country. Hearing of the plan, Musri contacted law enforcement and encouraged them not to let Choudary into the country. Eventually, the church resorted to asking television entrepreneur Ahmed Abaza, the prosecutor they had settled upon, to find them a suitable exemplar. He brought along Sheik Imam Mohamed El Hassan, a man with a limited online presence who claims to be, at once, a former candidate for president of Sudan, the owner of the Irving, Texas, branch of the 3g Network, and an imam at a small Sufi Islamic Center in Dallas. Musri phoned around to get a hold of El Hassan, but nobody in Dallas had heard of him. "I'm not sure if he exists, and, if he does, I doubt he's a real imam," said Musri.

The church opened its doors as re-scheduled at 4 p.m. on March 20—everyone was welcome but only 40 people came. Worst of all, the American media stayed away. Luckily, Ahmed Abaza had opened up a four-hour time slot to broadcast it live on The Truth TV.

"We organized everything to ensure a fair trial," Jones said. They reserved jury positions for volunteers, "first come, first serve," but when too few appeared, congregation members took the empty seats. Sitting behind his podium, four feet above the proceedings, Judge Jones read the three charges: "1) Crimes against humanity: training and promoting terrorist activities throughout the world. 2) Death, rape, and torture of people worldwide whose only crime is not being of the Islamic faith. 3) Crimes against women, against minorities, against Christians with the promoting of prejudice against anyone who is not a Moslem." This was followed by the four possible punishment methods, being voted upon by the visitors of the church website and Facebook. El Hassan was dismayed. No one had informed him about the possibility of Koran destruction.

The prosecution and the defense were each awarded two hours. Each side delivered their remarks in Arabic, pausing between sentences to give the interpreter (one of the defense's witnesses) the opportunity to translate into English. The prosecution called three witnesses; the defense called none. As the jury withdrew for deliberation, Jones took the opportunity to explain his court's judicial philosophy and, in the process, redefined the term "mock trial."

"In an American court, you cannot be found innocent or guilty without a consequence. If you're found innocent, then, of course, the consequence is very comfortable. You get to go home, you get to be with your family, you get to watch TV, you can Twitter. Because you're innocent. That is the result of your innocentness. That's the consequence.

"If you get convicted with murder," he continued, "you do not get to go home. It does not matter if we love you, if your mommy loves you, if your daddy loves you, you do not get to go home, ugh, because you have killed someone. You will face punishment. You will go to jail. You will… possibly… some day… be electrocuted! Or you will be shot up with poison… that is what justice is. And that is what will happen today. If the Koran is found guilty, there must be a consequence."

Jones proceeded to report the results of a poll offered on the church's website and Facebook page. Visitors had been encouraged to choose the appropriate penalty should the Koran be found guilty. "Unsurprisingly," as Jones conceded, they had overwhelmingly selected incineration. The court itself hadn't been completely impartial on that question in the run-up to the trial: a big white sign was stuck in the ground outside, reading "BURN IT!"

The jury required eight whole minutes to reach the obvious verdict on all three charges. Jones read it aloud, checking with the jury on every count. "In accordance with the example of American law," he transitioned seamlessly, "the Koran must be punished." Prosecutor Ahmed Abaza mounted an objection to the choice of penalty. Stepping to the microphone, he asked whether they could perhaps ban the Koran instead? Unfortunately, Jones didn't have those tools available to him, but he did have a Koran soaking in kerosene backstage. The disagreement was noted.

Apparently concerned for his channel's safety, Abaza cut his station's live feed before the burning commenced and left the room. StandUpAmericaNow.org picked up the stream. "Go ahead, Wayne," the judge signaled. Pastor Sapp—a small, pudgy, bespectacled ginger man who emulates Jones' stutter whenever he gets to pontificate—waddled in front of the podium, unmasked, and placed the Koran upright on a flat brazier. Jones asked once again if anyone wanted to leave. By "anyone" he meant El Hassan and his family, but they chose to stay. Finally, the anti-climax: Sapp pulled a stove lighter from behind his back, bent over, produced a flame, and held it inside the open book, soon producing the desired effect. The cameraman moved closer to capture the flames, cameras flashed—proof that they'd actually done it.

The news of the spectacle took longer to spread than the church would have liked. Few mainstream American publications mentioned it, cable news turned a blind eye. Dove Outreach depended on Afghan rioters to break the U.S. media's near-blackout of the story. Yesterday, in Mazar-i-Sharif, usually one of Afghanistan's safest cities, the first violent backlash occurred. Responding to news of the desecration, thousands of outraged protesters flooded a U.N. compound, killing at least seven foreign staff members. Back home in oblivion, Pastor Jones refuses to take any responsibility for the deaths. Instead, he feels vindicated. "This just shows you the dangers of radical Islam," he said. He calls the violent reaction "predictable"—an admission of willful incitement.

• John Avlon: Pastor Terry Jones’ Crocodile TearsImam Musri is worried that the violent outbursts in Mazar-i-Sharif are only the beginning. "All news channels are carrying this story now. Terry Jones has played into the hands of extremists on the other side—as he intended to. And their response will be fierce." One such extremist, Anjem Choudary, played right back into the pastor's hands. "Whoever insults the prophet, kill him," he said, as a matter of course. "It's the same as Theo Van Gogh. Sometimes the message has to be drummed home to people: Do not insult the prophet. Yet people still continue to do it and they will continue to face the consequences."

Unfortunately, precisely those arguments attract people like Terry Jones and his congregation of 30 to spectacular acts of Islamophobia. As long as insulting Islam generates a disproportionate response in the Middle East, reckless, attention-hungry Westerners will think up new, creative ways of insulting the religion. The only way to hurt a Terry Jones is to ignore him. His symbolic struggle against radical Islam is actually a tangible struggle against his own obscurity.

Leon Dische Becker is a freelance journalist/editor living in New York.