The ascent of the novel coronavirus in the Lone Star State has been a gradual one. But as the state reopens its economy, infection counts are surging—and experts warn of a potential flood in the months ahead.

On March 4, the state health department reported Texas’ first positive case of COVID-19. One month later, on April 4, there were 6,110 cases. As of Monday—May 4—approximately 32,332 Texans had tested positive for the coronavirus, with an overnight uptick of 784. About 7,035 of those cases were confirmed in just one week, according to data analyzed by The Texas Tribune. And that’s despite having one of the lowest testing rates in the nation.

Two counties lead the state’s cases. Harris, which includes the city of Houston and is the third largest county in the United States, had 6,967 confirmed cases on Monday and more than 130 deaths, according to Dr. Umair A. Shah, executive director for the county’s public health department. There were 129 new cases overnight, Shah told The Daily Beast.

On Sunday, Dallas County reported its highest new COVID-19 case total to date, with 234 additional positive results—just two days after Gov. Greg Abbott’s statewide shelter-in-place order expired. As of 10 a.m. Monday, the county had reported 237 additional positive cases overnight—another record—bringing the total case count there to 4,370, including 114 deaths.

Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins has repeatedly cautioned residents to continue social distancing despite Abbott’s decision to reopen businesses on Friday. Abbott was just one in a laundry list of mostly Republican governors who recently launched aggressive efforts to reignite pandemic-ravaged economies—even as epidemiologists warn of possibly grave consequences.

But amid evidence of nationwide quarantine fatigue and revised models showing a surge in deaths expected in connection with COVID-19, public health experts in the state were keeping their eyes trained squarely on long-term care facilities and prisons. That’s where they expected one of the most populous states in America to see its coronavirus future come into sharper, and more disturbing, focus.

“It’s going to be scary going into the fall,” said Diana Cervantes, director of the epidemiology program at the University of North Texas Health Science Center School of Public Health. “We’re going to see a huge explosion of cases.”

Neither Governor Abbott's office nor the Texas Department of State Health Services responded to questions from The Daily Beast on Monday. And to be clear, multiple experts warned that people leaving the house more often since the reopening may very well become infected, but that it would take days before symptoms present themselves, and longer to get test results—if they can even acquire a test. In other words, any new surge tied to the reopening would not be clear for at least a week.

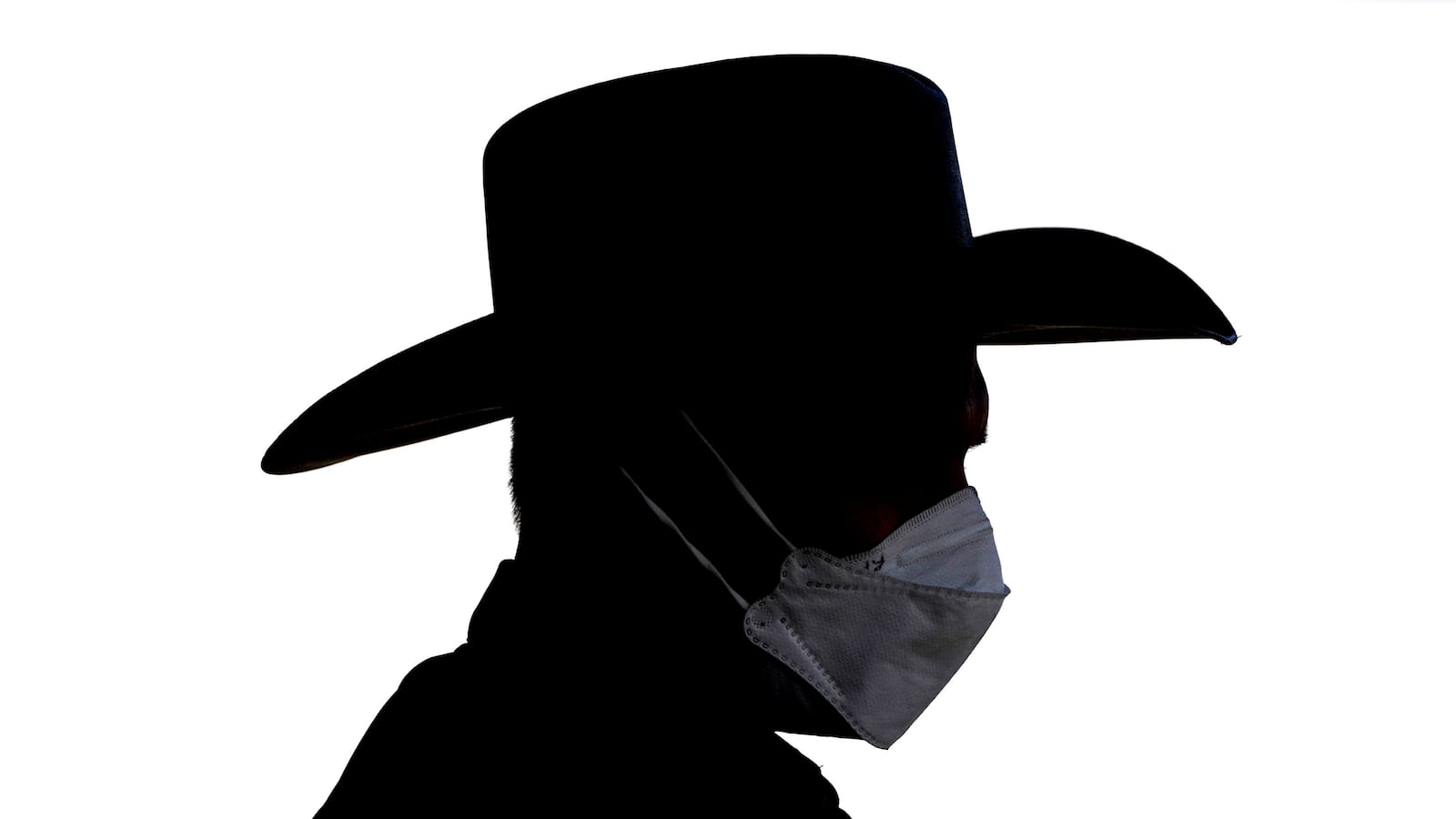

“For the state, the overall trend [of infections] is that the peaks are getting a little higher and a little wider,” said Cervantes. “I think people get fatigued on doing these types of foundational public health measures to prevent transmission, like social-distancing and wearing masks.”

As Dallas County data appeared to confirm on Monday, more than 40 percent of the state’s coronavirus deaths are linked to long-term care facilities, which an analysis by the Tribune and ProPublica found last week. Jenkins, the county judge, told The Daily Beast that he hoped his community followed “the science,” meaning the recommendations from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), public health officials, and major hospital chains in the area.

“They say that it’s too early to open, that we haven’t seen that two-week decline,” Jenkins said, referring to federal guidance calling for a 14-day drop in new cases. “In fact, in Texas we haven’t seen any decline. And we rank dead last in testing. So they’re telling us to brace for worse infections because we didn’t follow the science.”

State health authorities have so far refused to name the nursing facilities with known cases—or disclose the total number of infections across all such facilities in Texas.

Experts were sounding the alarm.

“What I am concerned about with reopening, is that, if facility staff broaden their contacts with people outside their household, then staff may acquire the virus and unknowingly bring it into the facility,” said Patty Ducayet, the state’s federally mandated long-term care ombudsman for more than a decade. “That’s a risk of expanding our social networks before we have widespread testing and ample PPE supplies for all.”

Jenkins said Dallas County was already “seeing a widespread outbreak in the general population.”

<p><strong><em>Do you know something we should about the novel coronavirus, or how your local or federal government is responding to it? Email Olivia.Messer@TheDailyBeast.com or securely at olivia.messer@protonmail.com from a non-work device. </strong></em></p>

“The main concern would be that the citizens would hear what the governor is saying and act on that and begin to do things like go to large group meetings, go to theaters, go hang out in restaurants and then spread a lot more disease and make this worse,” he added. “But at this point it’s up to each person in Texas to make good choices.”

One of the worst known outbreaks in Texas stemmed from an assisted living facility in College Station, about 95 miles northwest of Houston. But there are approximately 1,200 nursing homes and 2,000 assisted living facilities in the state, and last week the Texas Health and Human Services Commission reported 242 resident deaths in nursing homes and 61 fatalities in assisted living facilities, the Tribune reported.

Ducayet said the percentage of fatal cases impacting long-term care residents “shows just how vulnerable they are.” In some cases, she explained, a staff member working at more than one facility who may not have known they were exposed could have contaminated more than one facility.

Given the well-documented risks posed to the elderly by COVID-19, the lack of transparency about outbreaks there was glaring.

“Any place that’s a congregate living setting is going to be highly susceptible to increased transmission,” Cervantes said. “For any respiratory disease, we know that’s the case, be it influenza or measles—anything transmitted via respiratory droplet.”

Meanwhile, though Texas is behind a handful of other states—including Louisiana and Oklahoma—for the highest incarceration rate in the country, it has 104 prisons, which house up to 150,000 inmates. Separately, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice also oversees 17 state jails in 16 counties, and a researcher at the agency the Texas Commission on Jail Standards told The Daily Beast on Monday that the agency regulates 239 county jails.

As the pandemic spread through the state, the Beto Unit in Palestine, Texas, quickly became the biggest hotspot among Texas prisons, topping 200 cases last week, according to the Marshall Project. The Harris County Jail, on the other hand, was responsible for at least 132 of the cases in that county.

“In prisons and jails, the spread is like wildfire,” said Michele Deitch, a senior lecturer and prison conditions expert at the University of Texas law school. “And almost certainly the number of prisoners with the virus is much greater than they realize because they aren’t doing extensive testing.”

“What’s happening inside these prisons isn’t staying inside these prisons,” Deitch told The Daily Beast. “Staff are going back home to their communities each night.”

In addition to congregate spaces like prisons and nursing homes, meatpacking plants have been the root of several clusters in the state.

Last week, the CDC announced that processing facilities in 19 states had reported 4,913 cases and 20 deaths among meat industry workers, signaling the need for greater protections. This week, infection rates per 1,000 people in Texas counties with hot spots tied to meatpacking plants continued to climb, according to the Tribune. For example, Moore County—the home of the JBS Beef meatpacking plant—has the highest reported infection rate in the state at 18.30 cases per 1,000.

The plant—in a town called Cactus—is operated by about 3,000 workers, most of them immigrants from Mexico and Guatemala or refugees from elsewhere, according to the Tribune.

Amarillo Mayor Ginger Nelson said over the weekend that a team of federal officials would help “attack” those clusters. The Department of State Health Services has said it was looking into outbreaks at JBS Beef and Tyson Foods in Shelby County, near the border with Louisiana.

In Harris County, coronavirus cases were two to three times more prevalent in some of Houston’s poorest areas codes compared with the county overall, according to a Houston Chronicle analysis. The virus tended to cluster in predominantly black neighborhoods, the paper reported, in findings that mirrored a Georgia-specific analysis by the CDC last week, and larger trends showing COVID-19 hitting communities of color especially hard. Experts noted the high risk associated in some of these areas, where many residents have underlying medical conditions.

“Our concerns are obviously, now that we’re reopening, that we don’t want to go backward and see an uptick in cases and hospitalizations,” said Shah, the Harris County health official. Over the weekend, he said, he observed more people on blankets, out fishing, and playing frisbee without distance or facial coverings.

There will be a lag, he explained, between when those who venture out and possibly contract the virus develop symptoms or seek tests. That’s what health experts like him are bracing for.

“As people continue to come back into their lives, we want to make sure they remember this is not normal life as we knew it prior to COVID-19,” said Shah. “We just have to keep reminding people that we have to protect ourselves and each other. Otherwise we’re going to be in the same boat as we were before.”

Or, as Jenkins put it: “Just because the law allows you to do things ... doesn’t mean you must do those things.”