Parisians have chic, Italians have la dolce vita, Brits have Evelyn Waugh—and Americans will always have cool.

Defining “cool” is a bit like that famous Potter Stewart quote about hardcore pornography—“I know it when I see it.” Who you think is cool, and what you think makes them so, is incredibly personal and subjective.

But, a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., “American Cool,” attempts to create a definitive history of the progression of “cool,” our greatest cultural export, through 100 photographs of icons including Mae West, Jim Brown, and Quentin Tarantino.

“What do we mean when we say somebody is cool in America?” is the question the exhibition elicits, says one of the curators, Frank Goodyear III, who is co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

Goodyear, along with co-curator Joel Dinerstein of Tulane University, created a rubric of four factors (at least three had to be met for inclusion) to winnow down the list from over 500 possibilities to the current 100. The individuals needed to have an original artistic vision and style, be representative of their generation’s cultural rebellion, have instant visual recognition, and have a lasting cultural legacy.

While our modern sense of cool started with jazz musician Lester Young, the exhibition backdates its beginning to include two men the curators call the “granddaddies of cool”—Frederick Douglass and Walt Whitman. While the famously stern portrait of Douglass may not seem worthy by today’s standards, Douglass invented black public masculinity and became one of the earliest embodiments of the element of cool that says, “Don’t mess with me.”

Whitman, pictured in an engraving in the front of Leaves of Grass, captures the confidence (or arrogance) of an individual going completely against the establishment. This dogged pursuit of self-discovery becomes a theme throughout the exhibit and is seen in a range of characters, from beatniks like Jack Kerouac and brooding grunge rockers like Kurt Cobain, to inventors like Steve Jobs.

The exhibition is broken into four parts. The first, titled “The Roots of Cool: Before 1940” is probably the most educational of the sections, featuring men and women likely unknown to most people today.

Two of the women from this section are particularly noteworthy and relevant today. Long before Madonna, Bette Midler, and Lady Gaga, Mae West incorporated drag queens and prostitutes into her work and famously said, in a pre-code Hollywood film, “When I’m good, I’m really good; but when I’m bad, I’m better.” Bessie Smith, one of the most influential blues singers, was a prominent feminist who sang of lust (including of the same-sex variety) and partying, perhaps even more frankly than most men. Janis Joplin (who did not make the final cut) once said she thought of herself as the reincarnation of Smith.

There is a set of famous paintings by Andy Thomas, one of former Democratic presidents playing cards, and one of former Republican presidents doing the same. FDR gives an avuncular grin around his famous cigarette holder to Andrew Jackson. LBJ gives Woodrow Wilson his famous Johnson lean. Teddy Roosevelt guffaws while Nixon grins.

Walking through the second section of the exhibition, titled “The Birth of Cool: 1940-59” feels like you’re walking in on a similar dinner party, only with actors, musicians, and writers. Billie Holiday’s portrait sits between the two titans of the west, John Wayne and Gary Cooper. Robert Mitchum, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jackson Pollock hang nearby, and would make for interesting companions during a night out. Part of the purpose of the exhibition is to remove the lines society normally establishes (categorizing people into groups like jazz musicians, writers, actors, and so on) and to integrate these cultural icons into one group, creating a comprehensive picture of the cultural changes wrought by these men and women.

One of the towering figures of this era, jazz musician Lester Young, is likely an unfamiliar face for many in the modern audience, but he is arguably the most important in the exhibit. He was the first performer to wear sunglasses at night while performing, and his slang became popularized, in particular his use of the word “cool.”

“There is no separating cool from the history of race relations in America,” argues Dinerstein. According to the curators, the idea of cool in American culture comes directly out of African-American culture in the jazz era. In one of its more fascinating results, the exhibit serves as a timeline of the progression of cool among black men, starting with Douglass and continuing on to feature boxer Jack Johnson, Duke Ellington, Jim Brown, Muddy Waters, Muhamed Ali, Michael Jordan, Afrika Bambaataa, and finally ending with Jay Z. These images of African-American men and the messages they project to the world change as society changes. The proud defiance of Douglass stands in stark contrast to the too-cool-for-school nonchalance of Jim Brown, who grimaces while surrounded by adoring white reporters. And yet traces of both can be seen in the final picture, that of Jay Z, the multimillionaire outlaw who has society’s approval but still remains outside of it.

The exhibition also opens up a generational dialogue. Young viewers may struggle to explain the cultural importance of Missy Elliott’s “Get Your Freak On” to their elders, who, in turn, will be more familiar with historic individuals like novelist Raymond Chandler. Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, the iconic detective featured in his novels, was the popular antihero who was “beat, but not beaten.” That archetype is an all-too-familiar trope in American film and television now. Chandler’s work also provided a major influence for Ian Fleming’s James Bond, representing an early example of the export value of American cool.

This is also the era when the rare event of a star dying too young became an all-too-often occurrence. James Dean and Hank Williams burned bright and hard, with Dean in particular inspiring the adage “live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.” That sentiment is seen through the remainder of the exhibition, with individuals like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Bruce Lee, Selena, and Jimi Hendrix all having died at an early age.

The obvious inflection point in the show occurs with the jump from icons of the 40s and 50s, to those of the 60s and 70s. During this shift, the idea of cool goes from collected understatement (chill) to raw, naked, defiant emotion.

Few capture that shift better than Angela Davis, whose pyretic history as a Communist Party leader is perhaps only matched in notoriety by her afro, which became a political statement in its own right.

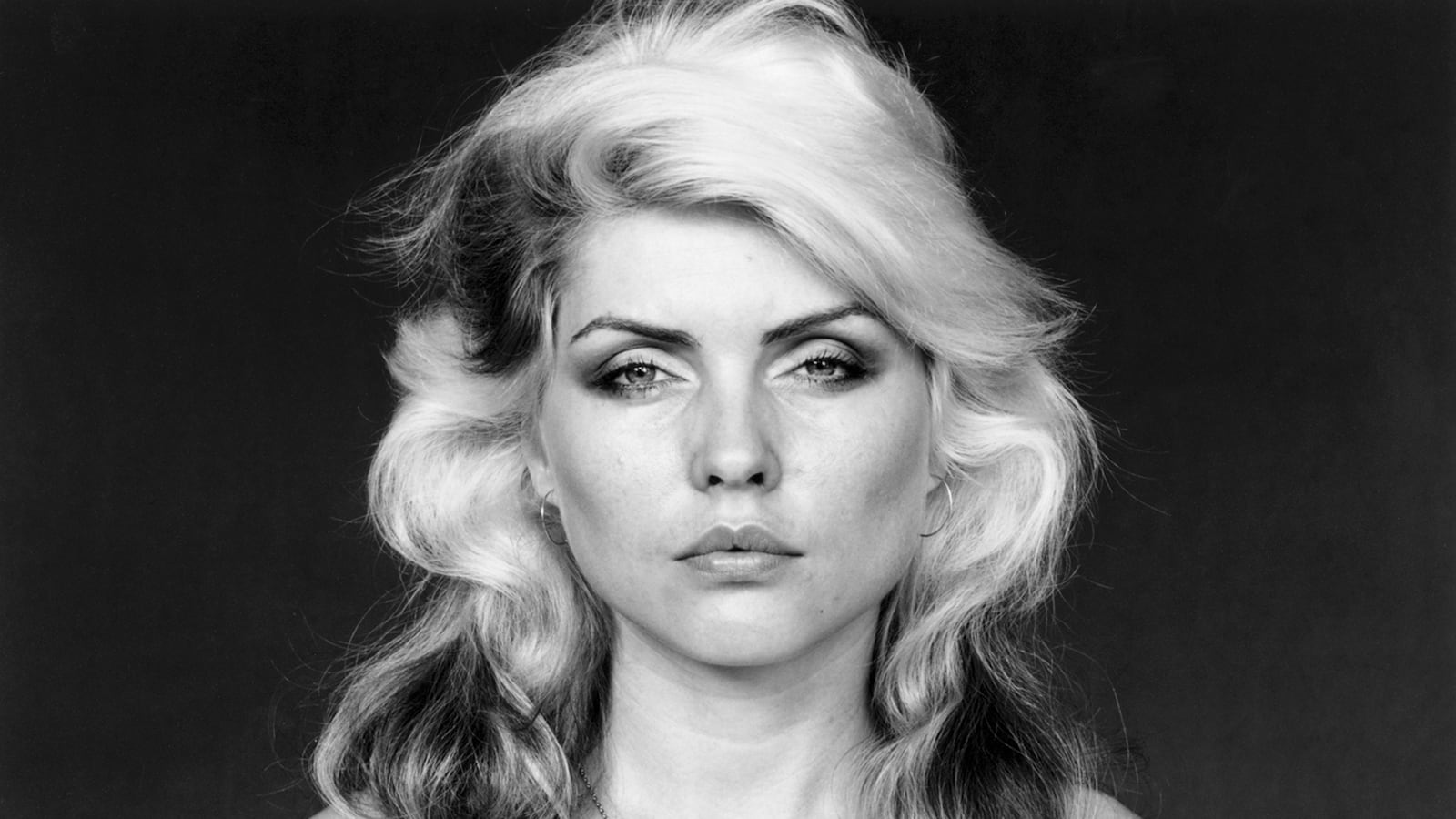

While arguably some of the coolest people ever, Muhammad Ali, Paul Newman, Hunter S. Thompson, came from this period, this is also the era, according to the curators, when women really carved out their own space in terms of defining “cool.” In particular, the female musicians featured, like Bonnie Raitt, Deborah Harry, and Patti Smith, who took a relatively masculine concept and made it one women could openly own.

Due more to the layout than anything else, most visitors will likely start at the end of the exhibit with “The Legacies of Cool: 1980—Present.” Full of eye-catching photographs of people easily recognizable today, this period marks a second major inflection point in the development of “cool,” when the concept was turned on its head and became as much about wealth as anything else. Whereas selling out was considered a crime in the 60s and 70s, by the late 80s and 90s, selling in, i.e. making money and thus gaining power, was the way to get on top. The faces seen here—Jay Z, Quentin Tarantino, Johnny Depp, Madonna, Prince, Bruce Springsteen, and Missy Elliott—could be mistaken for the annual Forbes list of the most powerful celebrities.

The question of whether this change is simply a product of those currently considered influential or is a true societal shift towards valuing the relentless pursuit of wealth is one that challenges an assumption at the heart of the exhibit’s premise. Were these people cool because they changed society, or were they merely the most prominent reflections of its changing face?

That “American Cool” focuses on photography is an effective means of forming a connection between the viewer and the featured stars. The pictures are evenly spaced and set against smoky blue walls, inviting viewers to immerse themselves in the moment. Because it is in the National Portrait Gallery, with prestigious works by Gilbert Stuart, Alexander Gardner, and Degas, the exhibition is also a study in 20th century portraiture, which came to be dominated by the camera. It’s a veritable who’s who of big name photogs—Leibowitz, Avedon, Halsman, Arbus. More important for the viewer, though, is the “sense of immediacy … that we can know the person … imagine ourselves there,” Goodyear says.

For those unable to make the trek to D.C., Prestel has published a fantastic book titled American Cool in conjunction with the exhibit. The glossy, entrancing photos are accompanied by excellent essays from the curators on how they approached defining the uniquely American attribute. In addition, each photograph has a neat aperçu sure to make for some interesting trivia at a dinner party.

In the end, if you’re left fuming because the curators overlooked your longtime hero or included somebody you cannot stand, remember, it really is a personal determination. In a nod to the subjective nature of defining cool, the curators have provided a comment book next to their Alt-100 list of those who missed the cut.

Or, do what the rest of us do nowadays, and send out angry tweets. Just make sure to use the correct hashtag, #AmericanCool.