Not that long ago, the cookbook was in grave danger.

Pundits were predicting that digital publishing would make ink-on-paper obsolete. After all, ebooks are easy to set, easier to revise, and effortlessly reproduced, warehoused, and shipped. They’re nonperishable—they won’t collect dust or get covered by pasta sauce! How could cooks and writers argue with that?

But then the unexpected happened: In 2018, hardcover, printed, huggable cookbooks were one of the biggest sellers. According to Forbes, unit sales in 2018 were up twenty-five percent, to a total of 17.8 million books.

We’re flummoxed, too. And we are cookbook authors—we’ve tried to fashion some kind of career around them. The publishers (now contending with an expanded universe of competitors, including regional and university presses, digital-first imprints, as well as authors publishing on demand) are privately giddy at their good fortune, but still scratching their heads. Why are people thrilled by the printed recipe, the food story, the glistening photo of a fish fillet?

One theory we favor, repeated to classes of would-be cookbook authors at our Cookbook Boot Camp every January, is that there’s a special and very attractive alchemy in the combination of inspiration, aspiration, and instruction that a well-crafted cookbook provides. And there now exists a broad market of people who purchase cookbooks, with differing motivations: some want a road map; others a jump-start; there are still others for whom the mere fantasy of cooking through the book is the journey. For most people, it might be a blend of these.

It’s only a theory, though. To test it, we decided to survey the people who need a cookbook least—authors like us—to find out what they purchase, cook from, and treasure most.

They are neither restaurant chefs nor TV stars (two common paths to publication), so they have no fallback plan, SAG-AFTRA card, or liquor license to calm them at night. Thrifty and opinionated, they are gifted only with the ability to blend work, pleasure, and sustenance in a simple meal cooked at home. We phoned to ask: what’s the most oil-splattered, juice-stained title in your kitchen library?

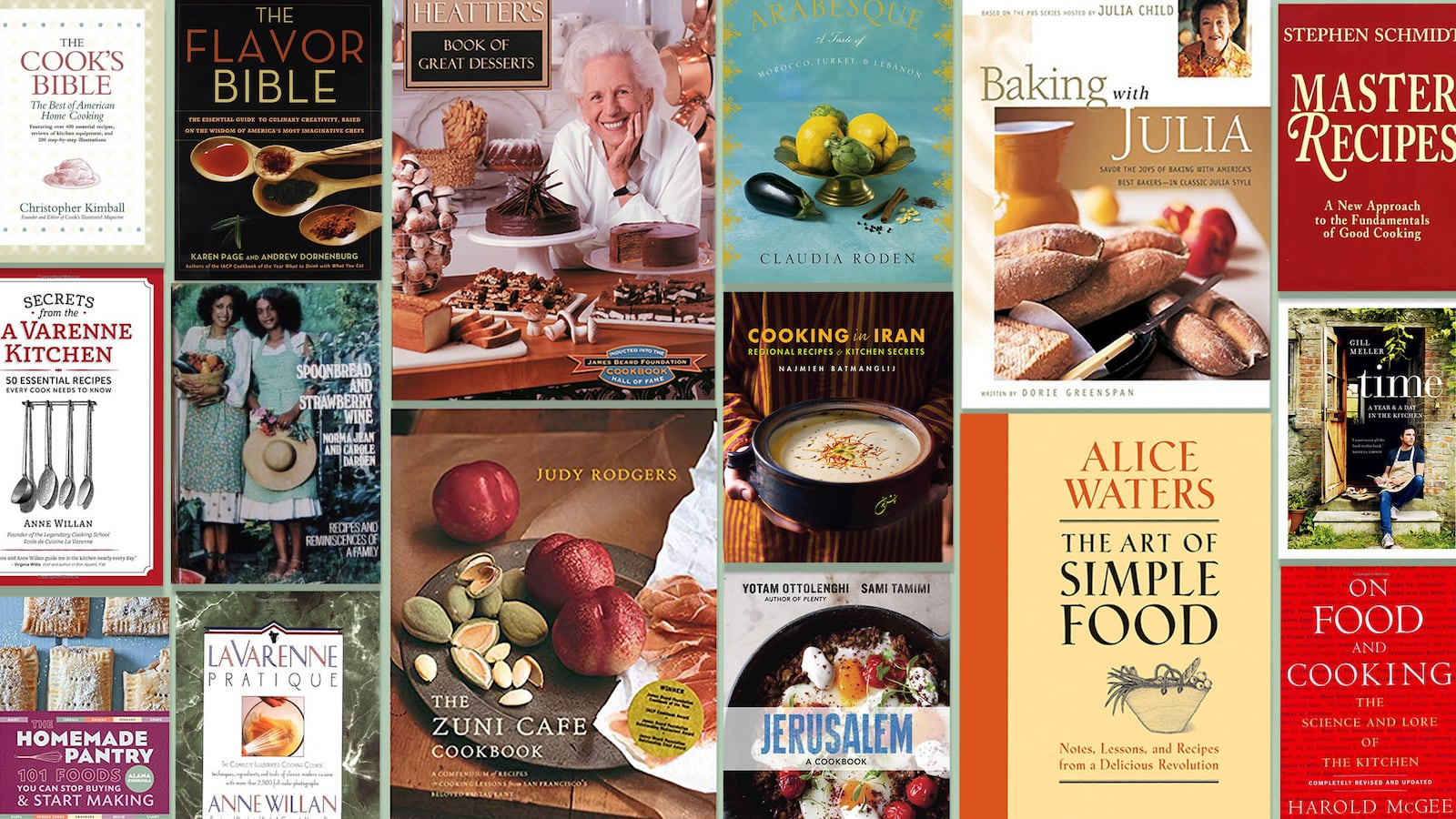

Of the ten authors interviewed, Jessica B. Harris, an expert on foodways of the African diaspora whose twelve cookbooks include The Africa Cookbook: Tastes of A Continent and Beyond Gumbo: Creole Fusion Food from the Atlantic Rim, took our question most literally, answering resolutely with a single book: Master Recipes: A New Approach to the Fundamentals of Good Cooking, by Stephen Schmidt. Our call found her at the bar of a hotel in Shanghai, where it was midnight and the bartender had just switched the lights on to encourage patrons to head back to their rooms. Harris was on tour for a cookbook—not her own, but a Chinese-language volume on the cooking of the United States, Foodways, written by Michael D. Rosenblum, a former chef for the U.S. Ambassador to China. Harris was a source on the subject of African-American cooking for Rosenblum’s book, and he invited her to join him presenting the book to Chinese readers. They’d been to Beijing, were headed to Shenyang the following day, and as she finished her glass of wine before closing time, she expounded on Master Recipes. “Stephen was a former colleague of mine in the English department at Queens College, we were these bizarrely culinary English teachers.” First published in 1987, Master Recipes is a 940-page tome that aimed to be The Joy of Cooking for a new era (and in fact, Schmidt was a main contributor to the 1997 and 2006 editions of the latter book).

“I’ve got one copy of Master Recipes in Brooklyn and another in Martha’s Vineyard,” Harris said. “I’m a very simple home cook, an intuitive one, but I need to know what temperature that lamb should be, how many minutes before it’s medium-rare. Master Recipes is timing and technological stuff, not ‘What spices do you want to put on it?’”

Like Harris, the Paris- and New York-based cookbook author Dorie Greenspan could point to a single title as most-used—her 1974 first-edition of Maida Heatter’s Book of Great Desserts. “It’s a treasure, the book I credit with teaching me how to bake,” she said from her Paris apartment. “The spine’s still intact, but it doesn’t have a cover. I’ve written all over it and every page is spotted.” But Greenspan, whose thirteen cookbooks have won five James Beard Awards and two IACP Cookbook of the Year Awards, noted that a recent foray into that volume (brushing up on the Buttermilk Lemon Cake on page 116 that she planned to make for an instructional video), made her realize just how seldom she cooks from other people’s books anymore.

“I cook from ingredients, what I’ve got in the pantry. What you develop is a certain style, a palette, a way of putting ingredients together, you’re not conscious of it, but that’s what comes into play when you open the refrigerator.”

But that hardly means Greenspan doesn’t consume contemporary cookbooks. In fact the opposite is true: “Every time I read something about a book, I buy it,” she said, noting that her wall of cookbooks had grown into a “cocoon.” Recent purchases include Time and Gather, books by Gill Meller, a chef at the River Cottage restaurants in England. “I bought both books because I was so taken by the feel of his food. But [they] didn’t send me into the kitchen.”

“What makes the cookbook world so exciting now is there are so many narrative books, so many stories, so many different ways of presenting your own food, of places you love,” Greenspan enthused. “The books that influenced me [early in my career] were more: here is the recipe. It’s exciting that they’re so personal now, that there’s so much to hold onto. I appreciate that the cookbook world has gotten larger and encompasses so many types of books.”

One author who spoke directly to those dual impulses—toward narrative and technique—was the food writer Nicole Taylor, whose The Up South Cookbook: Chasing Dixie in a Brooklyn Kitchen, tells her story of moving to New York from her native Georgia and gaining a fresh perspective on the foods of her childhood. When we reached Taylor at her home in Brooklyn, she said, “I use cookbooks for two things—I have my stack to cook from because I know the recipes work, and then the ones I read like novels.” In the latter category is the 1978 classic, Spoonbread and Strawberry Wine: Recipes and Reminiscences of a Family, by Norma Jean Darden and Carole Darden, New York City restaurateurs and caterers. “I haven’t cooked a single thing from it, but that was probably the biggest inspiration for my own cookbook. And the cover! They’re both standing there, gorgeous and tall. I keep going back to it for the stories, they’re so beautiful, they went deep into their family members, and they’re characters!” For hard kitchen reference (by now it’s dawning on us this may be the main reason confident cooks seek cookbooks), she names The Homemade Pantry: 101 Foods You Can Stop Buying and Start Making, by Alana Chernila, a guide to scratch-made pantry staples like cake mixes, granola and granola bars, ricotta and yogurt, which Taylor said she used to craft holiday gifts to give to friends and family. Taylor, a new mom whose six-month old baby boy cooed in the background as we spoke, added, “[Chernila’s] super clear about what she’s doing, the headnotes give a lot of practical tips and alternatives, but not anecdotes. I’m not getting in to bed with this to read or go to a faraway place.”

Forget the bedroom: Virginia Willis, the author of six cookbooks, including the James Beard Award-winning Lighten up, Y’all, won’t even take her favorite cookbooks into the kitchen!

“It’s not that I’m not an O.C.D. neat-freak, but when I was coming up, I worked with Nathalie [Dupree, a former cooking-school director and TV show host, the author of fourteen cookbooks including Mastering the Art of Southern Cooking, and winner of four James Beard Cookbook Awards]. Nathalie’s library was strictly a research library, the books had to be taken care of, respected.” Dupree would direct Willis to Xerox a recipe from a book and return it immediately to the shelf, so only the duplicate ever made it to the kitchen counter. To this day, Willis follows the same protocol, the only change being the “Xerox” in the kitchen today is a printed out iPhone photo.

“The books I’ve used the most come directly from my training,” she said. After working for Dupree in the early nineties, Willis attended L’Académie de Cuisine in Maryland, and upon graduating traveled to France, earning her grand diplome from l’École de Cuisine La Varenne, a school founded by the British-born writer, editor, and educator Anne Willan. “La Varenne Pratique is the big technical tome that explains everything,” Willis said. “There are recipes in it, but it’s not really about them, it’s about the how. And Secrets from the La Varenne Kitchen: 50 Essential Recipes Every Cook Needs to Know, I find myself using all the time. I don’t have to worry the gougères won’t work, or if I can’t remember the proportions of the swiss meringue that I’ve done a thousand times, I can look it up. Other than my teachers’ books, the only other book I always go to is On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee, because I’m looking to see what to do or how to do it, not just to follow a recipe.”

As a busy recipe developer and cookbook author, Willis noted her kitchen time tends to be defined by whether it’s work or leisure. “Cooking dinner is just cooking dinner, and testing recipes is more structured work,” she said. “I usually keep a notebook in the kitchen and if I’m cooking dinner, I’ll scribble. People always ask: ‘What’s your inspiration?’ Everything I put in my mouth! You never know.”

Other authors implied a looser, more fluid balance between work and play time in their kitchens. “My daily practice is mostly me making things up, cooking off the top of my head,” said Klancy Miller, author of Cooking Solo: The Fun of Cooking for Yourself and a recipe developer for The New York Times Cooking and Food & Wine. “I don’t regularly cook from cookbooks every night, but the ones I break out for special occasions have my go-to recipes that I love.”

Among these latter books, she could rank the recipes by how stained their pages are. “I have three splattered cookbooks in front of me,” she said from her home in Brooklyn, and within each of those volumes, she’d found the page most marked. Top billing went to “The Best Chocolate Cake” from Christopher Kimball’s The Cook’s Bible: The Best of American Home Cooking. “When I came back from France after training at Le Cordon Bleu,” Miller said, “I was broke and living at my parents’ house. I would reach out to friends in Philadelphia and say I’m doing a pop-up bake sale.” She sold slices of that cake and “Bocanegra Cake”—her third-most-splattered recipe, a bourbon-spiked flourless chocolate cake from Dorie Greenspan’s Baking with Julia.

Miller said she turns to both books frequently as references, and credited The Cook’s Bible with helping put her on the path to understanding the structure of a well-written recipe. “Everything’s so well-tested, and that rigor helped inform me in terms of understanding that recipes have to be tested, that you have to be able to talk about what to expect, what the finish product should be, what alternatives might look like in terms of different flours, different frosting, to anticipate different variations. These are recipes I can trust.”

Miller’s second most-stained recipe is the “Mejadra” from Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi’s Jerusalem: A Cookbook. One of the simplest recipes in the book, this lentil and rice dish “hits my favorite sweet-spots,” Miller said. “I’m a low-key health nut and this is filling, but not laden with sugar or fat. I love the flavors—allspice, basmati rice—and texturally, I like it a lot: crunchy, but tender. I got this book for my parents. They love the Middle East, it’s symbolic of what we like, the kind of stuff we eat frequently.”

Nik Sharma, writer and photographer of the award-winning blog A Brown Table and a San Francisco Chronicle column, A Brown Kitchen, is also working through a Middle Eastern moment in his kitchen, with the help of books by Claudia Roden and Najmieh Batmanglij. Sharma’s cookbook, Season: Big Flavors, Beautiful Food, was one of the most praised of 2018, and he confessed straight off-the-bat, “I have way too many cookbooks!” (He recently estimated his collection at more than 400 volumes.)

Sharma classified the ones he uses most into three broad groups: those geared toward home cooks (“I lean toward British authors—Diana Henry, Nigel Slater, Nigella, Ottolenghi”); reference titles like The Joy of Cooking and Good Housekeeping (“Old copies that I look to for a historical perspective of what’s happening in this country”); and books he dives into to immerse himself in another culture, such as Claudia Roden’s Arabesque and A Book of Middle Eastern Food, and Najmieh Batmanglij’s Cooking in Iran.

Sharma acknowledged his kitchen process so often involves cross-pollinating, from one cookbook to another, and he resisted our appeal toward a single, most-often-used title. “When I see the same recipe done [differently] in different books, I want to understand why,” he said from his home in Oakland. “What made it special? Take preserved lemons—a lot of people are doing it differently, the way they’re cut, the types used, the ratio of the salt, some people use sugar. What is the story behind each recipe in terms of the culture of the people?”

Speaking more generally, Sharma said, “The books I come back to are the ones that home cooks use, that reveal tricks I can use, which I find really helpful.” He added, “I rarely cook out of a restaurant cookbook because what a chef has at their disposal, the way they think, is totally different.”

We agree with Sharma on that last point—it can be a challenge for restaurant chefs to translate the kind of cooking that happens “on the line” for a mass audience, whose home kitchens are so differently provisioned, equipped, and worked (a restaurant chef we know once published a recipe for cornbread whose first step was: “Preheat your oven to 700 degrees.”)

But as it happened, our next author, the Paris-based David Lebovitz (reached while traveling in San Francisco), offered up two books widely known for their precision and cookability that were, in fact, written by California restaurant chefs. Lebovitz cooked for thirteen years at Chez Panisse in Berkeley and, since 1999, has published eight cookbooks including The Perfect Scoop, among the top-selling ice cream cookbooks of the last decade.

Lebovitz’s first pick was The Zuni Cafe Cookbook, by Judy Rogers. “Judy’s food isn’t easy, but the recipe always comes out as she says it’s going to, they all work,” he said. “Her brown-sugar brine makes the pork moist and perfect. And aillade—the joke used to be every time you went to Zuni, there was at least one thing you had to ask the waiter about. Aillade is pistachio pesto and it’s great on fish, grilled chicken, steak, even toast with an aperitif.”

“Another I use quite a bit is Alice Waters’ The Art of Simple Food,” he said. “I like to improvise when I cook, but how much water do you put in for polenta? How do you make pizza dough? The basics are in there, without a lot of filler, so I can go experiment on my own.”

“And I don’t want to sound arrogant, but I use my own books a lot,” Lebovitz said. “I think cookbook authors all use our own recipes because we know they work, we know their quirks.”

Karen Page and Andrew Dornenburg, the husband-and-wife food writing team, authors of eleven books, including the James Beard Award-winning The Flavor Bible and What to Drink with What You Eat, even claim that they use their own books exclusively.

“We don’t really use cookbooks to cook anymore,” they wrote in an email. “At this point, we’re mostly looking for ‘idea-starters,’ e.g. ways to use the leftover ricotta we just bought for another dish so it doesn’t go to waste, or how to create a pasta that offers a change of pace from the one we had just the other night. And our own books The Flavor Bible and The Vegetarian Flavor Bible kind of cover that for us. (We suspect many of us write the books we most want to cook from that don’t yet exist!).”

The next book they’re working on that doesn’t yet exist is The Flavor Atlas, which “will focus on cooking with flavors and techniques from all around the globe—both authentically, and also as a point of inspiration for creative spins on tradition.” Their editor called it “A geographical guide to global food that offers insight into the flavors and ingredients of every influential cuisine on Earth.”

So there you go, another cookbook we all need.