As newspapers and magazines and newscasts and a bestselling book and a TV series told of the 10 bodies found along Gilgo Beach, three other Long Island serial killer victims from a decade before went largely forgotten by everyone save their loved ones and the cops.

All three of the earlier victims were women. Each was found battered to death in a wooded area and posed with legs open, arms pulled back, and left shoe missing. Semen was recovered from two, 31-year-old Rita Tangredi and 20-year-old Colleen McNamee. DNA showed it was from the same man.

This was between late 1993 and early 1994, at the dawn of such forensic investigation, more than five years before the premiere of the show, CSI, that made it part of popular culture. The most the detectives of the Suffolk County homicide squad could do was compare the DNA with possible suspects.

“It was all new,” says Detective Sgt. Charles Leser of the Suffolk County Police Department.

In time, homicide detectives tested the DNA of dozens of suspects, without a match. They continued to test everyone who was busted for a sex crime, and even motorists who incurred a traffic infraction near a local red-light district.

“They did it for years,” Leser told The Daily Beast.

In 1996, a New York State DNA databank began what was termed “limited operations,” initially collecting samples only from those convicted of homicide and some sex crimes. The state databank grew and became part of Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS.

By August of 2012, the applicable New York state law had been amended five times, gradually broadening mandatory collection to include everyone convicted of a felony or misdemeanor.

In June of 2013, senior probation officer Elena Mackie, who handles domestic violence cases, collected a mouth swab from 44-year-old Timothy Bittrolff upon his conviction for violating an order of protection. The sample was entered into the CODIS database and the Suffolk County homicide squad was notified of a partial, familial match with DNA recovered in two of what might be called the Left Shoe Murders.

Timothy Bittrolff has a number of relatives in the area and the detectives asked the Suffolk County crime lab if it could narrow the finding. The lab reported back.

“It’s a sibling,” Leser recalls.

As the DNA came from semen, that meant a brother. The squad discreetly determined there were two, John Bittrolff and Kevin Bittrolff. The detectives guessed from the start that John was the more likely suspect, as he was older and would have been 27 at the time of the killings. Kevin was six years younger and would have been just 21.

The squad placed both men under surveillance with the hope of retrieving something from which they could obtain a DNA sample. The detectives employed such uncoplike vehicles as a plumber’s van, but John almost immediately spotted the tail.

“From day one, he knew we were following him,” Leser says.

John at one point stopped at a railroad crossing and just sat there until the detectives drove past. Another day saw him make a sudden right, then an immediate button hook.

“Evasive driving,” Leser says.

John is a carpenter, and when on a job he would seek a high vantage point.

“He’d stand up on the roof, looking for us,” Leser remembers.

In the meantime, younger brother Kevin had been down in Florida with their mother. The detectives followed him upon his return to Long Island and saw him toss a cigarette butt out his sports car window on a local parkway. Kevin drove on unawares as one unmarked police car behind him swung across the road to block it and a detective hopped from a second car to retrieve the source of DNA.

The lab determined that Kevin’s sample was another partial match with the DNA from the murder victims. That left only John, but the detectives still wanted a sample of his DNA before arresting him. He seemed to anticipate their intentions.

“I think in the back of his mind he was nervous,” Leser says. “He never discarded something personal.”

The detectives observed him drinking beer at home and hoped that he would eventually put the bottles out for recycling.

“That never happened,” Leser says. “He had tons of beer bottles. I don’t know what he did with them.”

The detectives finally decided to check his household garbage. They searched it themselves to spare the lab the unpleasantness, looking for cups, straws, and anything else that might have a trace, taking photos of each item they extracted and subsequently submitting them for testing.

The lab quickly reported finding DNA from an unknown female and two males related both to her and to the killer. The female was the suspect’s wife and the two males were their sons.

“If you take the female DNA and the suspect DNA, they make the two kids,” Leser says. “It’s like a paternity test.”

In July of 2013, the detectives pulled John Bittrolff over as he was driving to work. He offered no resistance and gave little outward indication of whatever he might have been feeling.

“It’s hard to tell with him,” Leser reports. “He said, ‘Oh, I’ll go with you.’”

At Suffolk County Police headquarters, Bittrolff agreed to a videotaped interview. Leser informed him that the detectives were looking into the murder of two prostitutes.

“Really,” Bittrolff said. “Interesting.”

“Have you ever used the services of a prostitute?” Leser asked.

“No, never,” Bittrolff replied. “I can get laid any time I want. I don’t want to bring disease home to my wife.”

Leser presented Bittrolff with photos of the two victims, shots taken both in life and at the crime scene.

“I don’t even recognize this girl,” Bittrolff said of Tangredi.

“I have no idea who this is,” he said of McNamee.

Leser told Bittrolff that semen had been found in both victims and it had been linked to him.

“To me?” Bittrolff asked. “Really?"

He added. “It surprises me, yes, because it’s not me.”

Bittrolff insisted that the detectives could not possibly have his DNA. Leser told him about the results from the garbage.

“Now I need a lawyer,” Bittrolff said.

The video camera was recording when Bittrolff called his wife, whose name is tattooed on his arm. She is the mother of his two sons, one of whom was a toddler at the time of the murders, the other not yet born.

“Hello, it’s me… I got arrested… I’m not kidding you. I’m dead serious. Two murders. From 1993. Two prostitutes. They’re saying they found my semen in them.”

The detectives had offered Bittrolff something to drink and he had accepted it. The cup carried DNA that provided direct confirmation.

“It all matched,” Leser says.

With a court order, the detectives and the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office obtained a mouth swab that reconfirmed the result and made it official. A spokesman for the DA later reported the odds of the DNA from the semen in the two victims belonging to someone other than Bittrolf.

“One in 81.6 quintillion,” the spokesman said. “That’s quintillion with a Q.”

The lead prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney Robert Biancavilla, described the unexpected DNA hit that led from a brother to a killer a decade after the crimes.

“The fish just happened to jump in the boat,” Biancavilla said.

But that great luck had been accompanied by considerable work on the part of the some uncommonly dedicated detectives, beginning with those who originally worked the case and collected the semen from the victims and continuing with Leser and the others who matched the hit with John Bittrolff.

The detectives now on the case sought out the two original investigators—Detective Doug Mercer and Detective Robert Vessichelli, both retired—and told them their good work had finally paid off.

“They were happy,” Leser says simply.

The detectives now on the case set to learning all they could about Bittrolff’s background.

“We don’t stop at an arrest,” Leser says.

Bittrolff was described by some to be a good and helpful neighbor. Others reported that he had killed small animals when he was a youngster and he had grown up to kill deer seemingly just for the sake of killing and had raised a pig, then slaughtered it with gory gusto in front of neighbors. He had earned a nickname.

“They called him Crazy Johnny B,” Leser says.

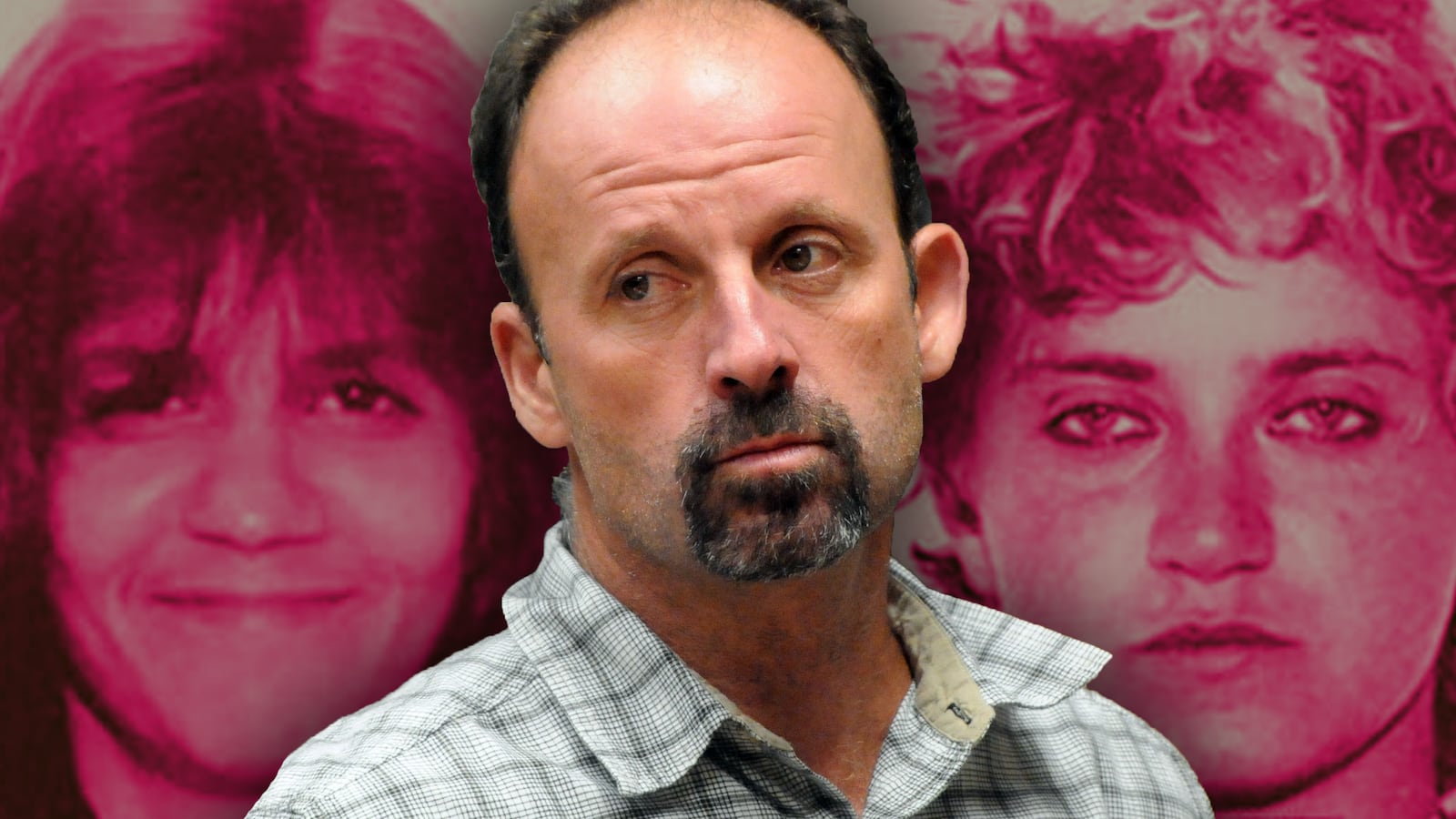

In May, Bittrolff went on trial for the murders of McNamee and Tangredi. The DNA remained the only significant evidence and the jury deliberated for seven days, declaring itself deadlocked three times before returning a guilty verdict.

The sentencing was on Sept. 11 and Tangredi’s son, Anthony Beller, addressed the court. He had been just 11 years old when his mother was murdered.

“What do you say to the person who killed your mother?” Beller said. “Forgiveness. I do hold some forgiveness for you, John Bittrolff. But I also believe in justice.”

Beller now had children of his own who wondered why they had never met his mother.

“You are the monster in that story,” Beller went on to say. “All I see is an unremorseful animal.”

McNamee’s brother, Thomas McNamee, also spoke.

“You’re a disease to society, a killer who will always pose a threat to society,” he told Bittrolff.

Bittrolff was sentenced to the maximum, two terms of 25-years-to-life, to be served consecutively. The lead prosecutor spoke afterward to the Associated Press and suggested there might be a link between Bittrolff and the Gilgo Beach murders.

“There are remains of the victims at Gilgo that may be attributed to the handiwork of Mr. Bittrolff and that investigation is continuing,” Biancavilla said.

The remains in question were apparently those of a woman, whose head, hands, and legs had been found on Gilgo Beach in 2011. Her torso had been found a decade before 40 miles away in Manorville, the Long Island town where Bittrolff lived with his wife and sons.

The homicide squad did not seem convinced of the link, but it is no doubt investigating. The detectives seem to have little doubt that Bittrolff had killed the third woman who had been found posed with her left shoe missing, Sandra Costilla.

The Left Shoe Murders had been solved as a result of two tenets that cops at their best apply to all homicides, no less so in cases where the victims are largely forgotten except by their loved ones.

The first tenet as voiced by Leser is, “It’s a matter of personal pride, and it runs deep.”

The other is particularly worth remembering.

“We truly believe that a life is a life,” Leser said.

UPDATE: In July 2017, John Bittrolff was convicted of double murder for the killings of Tangredi and McNamee. He received consecutive 25 years-to-life sentences for the murders. After his sentencing, authorities announced he was being investigated in connection with the murders of 10 women, mostly prostitutes, who were victims of the unidentified "Long Island Serial Killer."