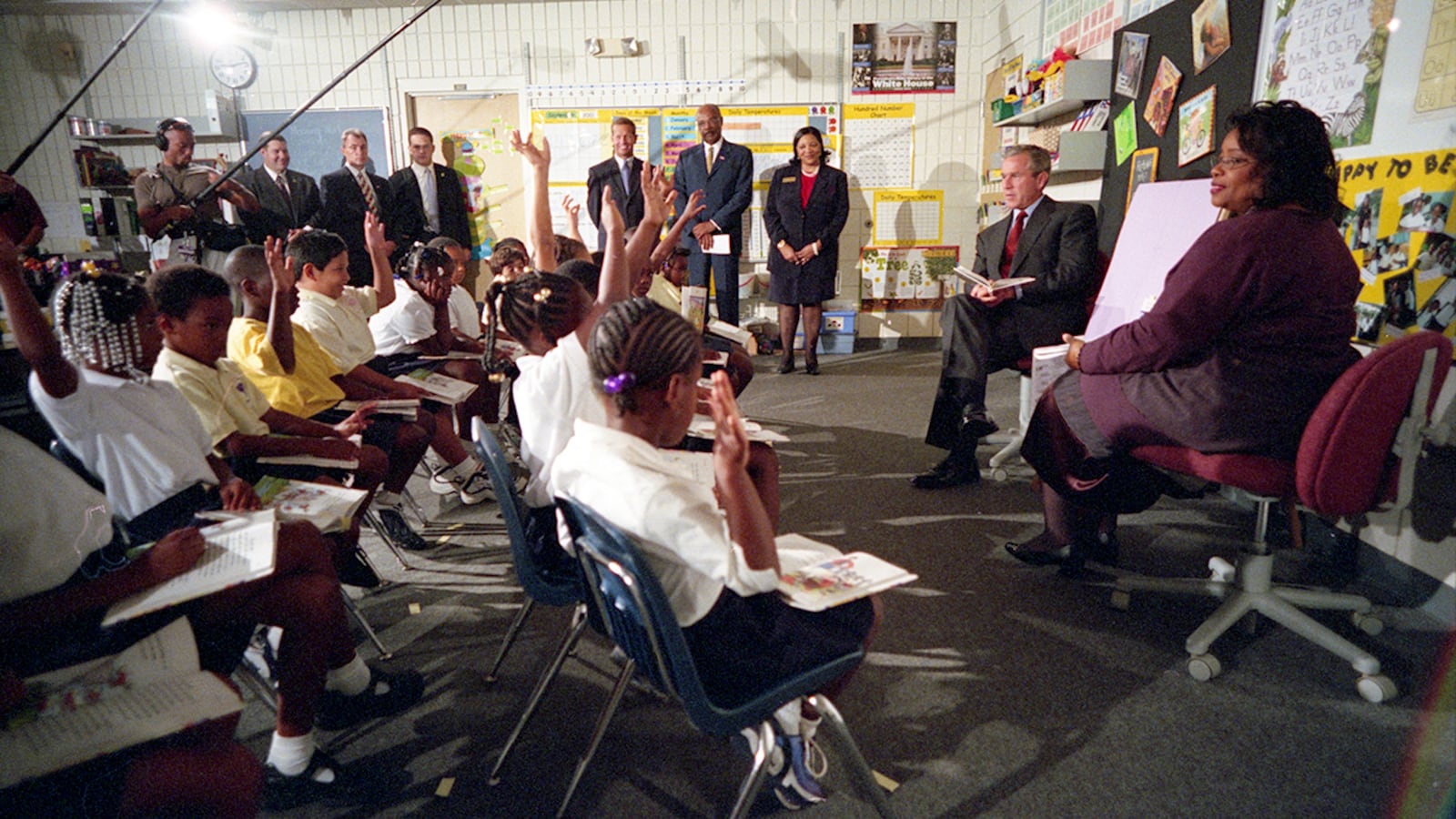

Everyone remembers the footage of then-President George W. Bush sitting in a second grade classroom at the Emma E. Booker Elementary School in Sarasota, Florida, reading along to The Pet Goat, when he was informed that two terrorist-hijacked planes had crashed into the World Trade Center towers. While 9/11 Kids naturally begins by revisiting that fateful moment, for which the commander-in-chief was roundly mocked, Elizabeth St. Philip’s documentary isn’t interested in investigating Bush’s immediate and long-term responses to the attacks. Rather, it’s a portrait of the now-grown Emma E. Booker boys and girls who processed 9/11 through the prism of this unique filter, and the manner in which that momentous day shaped their futures.

Premiering online at DOC NYC (Nov. 11-19), 9/11 Kids winds up rehabilitating Bush’s reputation for The Pet Goat episode by illustrating that, even though the kids instinctively knew something had changed after an associate whispered the earth-shattering news in his ear, the president remained blank-faced—and finished his appearance—as a respectful gesture toward children who had eagerly anticipated his company. Nonetheless, the prime focus is on the male and female students who were in attendance that early September morning. Their lives took multiple paths in the ensuing years, and what their sagas illustrate is the confluence of hardship, prejudice, and economic disparities that define growing up in financially disadvantaged communities. But when it comes to tying those topics back to 9/11 itself, well, it mostly falls short.

If there’s a person whose adulthood was directly influenced by his immediate connection to 9/11 and Bush, it’s La’Damian Smith, who now serves as a private first class in the United States Army. Both Smith and his wife admit that his service was born, in part, from the national tragedy; as he remarks, “it definitely makes me feel on-edge, that there could be more attacks of that nature.” Seen training at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri, Smith comes across as an enthusiastic soldier compelled to enlist out of a desire to have a role in preventing, and responding to, foreign and domestic threats. He is, in short, the ideal center of attention for a non-fiction film like 9/11 Kids.

Aside from the fact that 9/11 inspired him to volunteer for active duty, however, St. Philip’s film has nothing else to say about Smith, which underscores its general thinness. That superficiality is then reinforced by its collection of related vignettes about Smith’s classmates. At every turn, 9/11 Kids is blessed by charismatic subjects. Alas, it fails to draw either direct or indirect lines from their 8-year-old experiences on 9/11 to their current midtwenties predicaments. And in lieu of that missing connective tissue—which, given the doc’s title and premise, is essential to its entire existence—it provides snapshots of life in 2020 America that, however revealing, are no different than millions of others in this country.

Centering on individuals living on the wrong side of train tracks that literally separate Sarasota’s white and black enclaves, 9/11 Kids details the many ways in which these students have, post-graduation, grappled with arduous obstacles. Natalia Jones-Pinkney strives to launch a daycare business while dealing with her own tykes, a sick mother, and a brother who was shot by police officers in a newsworthy incident for which he faces serious impending charges. Tyler Radkey contends with a drug-related arrest that could net him time in prison. Entrepreneur Dinasty Brown grows her booming online consulting company for social media marketing. Lazaro Dubrocq supports his immigrant parents by working as a chemical engineer. And Megan Diggins endeavors to speak out against domestic violence after an altercation between her abusive boyfriend and another ex left her permanently paralyzed from a gunshot.

The battle against adversity is the common thread uniting these disparate men and women, and 9/11 Kids illustrates how their circumstances are microcosmic reflections of larger ongoing debates and crises about race, immigration, and inequality. The song that second grade teacher Kay Daniels played for her class on the morning of 9/11—Sounds of Blackness’ “Hold On (Change is Comin’)”—thus remains a mantra for her students, who’ve been forced to grapple with misfortune. For a few of them, such as Lazaro and Dinasty, persevering and thriving has been a natural process; as the latter proclaims, “In order to get better, you have to go and get it. It’s not going to come to you. So that’s why I push myself so hard.” For Tyler, however, it’s a struggle that continues to this day.

That some of Daniels’ students have flourished and others have navigated bumpier courses is no revelation; one imagines any 20-years-later look at an elementary school class would result in a similar cross-section of stories. The distinguishing hook of St. Philip’s film, though, is that these boys and girls were supposedly impacted in a fundamental fashion by their association with President Bush on 9/11—and that facet is largely absent from these proceedings. Without that unifying narrative thread, one is left to wonder why these particular narratives are more worthy of cinematic treatment than any others—a notion exacerbated by the fact that St. Philip leaps between them fitfully, such that only skin-deep impressions are imparted.

To tether its strands, 9/11 Kids employs WRBA radio broadcaster Ronnie Phelps as a narrator charged with pontificating about the state of both the Union, and divided Sarasota. Phelps is a charming and eloquent personality, but though his commentary is cast as part of a broadcast (he’s routinely seen sitting at his studio console), it’s clear that these sequences have been staged—and possibly scripted—for the screen, which amplifies their corniness. At least a good deal of what Phelps has to say about the challenges faced by minority communities is on-point, and timely. Yet thanks to a lack of thematic precision, it’s frustratingly difficult to discern how such issues pertain to 9/11, which is the nominal point of this entire affair. It’s a film with an abundance of heart but a muddled purpose.