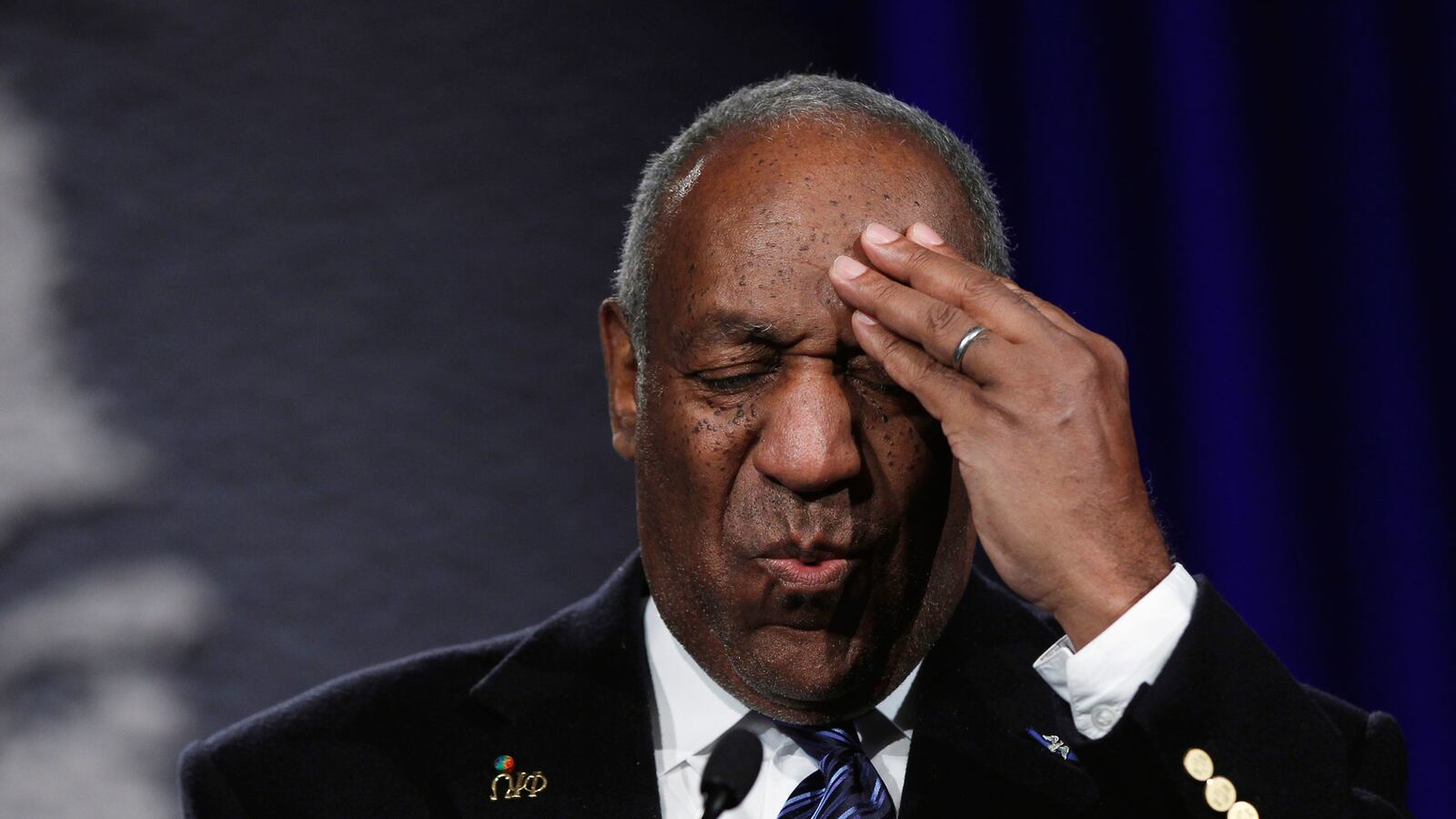

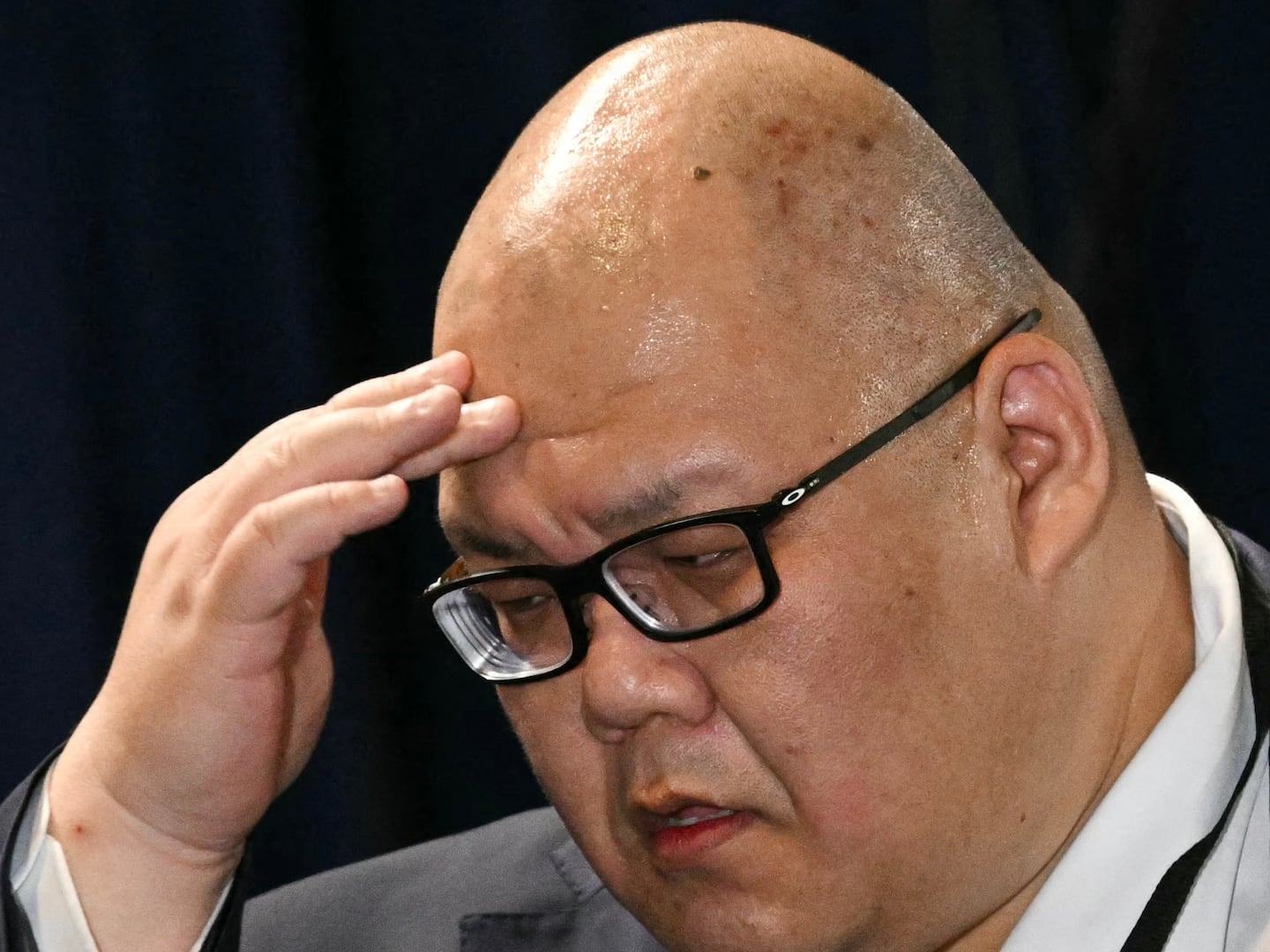

Every so often, as he tries to explain, defend and justify his decision to omit the rape allegations from his biography of Bill Cosby, Mark Whitaker sighs.

“Well, look, obviously the story has changed, and I’m going to have to address that in future editions of the book, if not sooner,” Whitaker says, exhaling. “If it happened, and it was a pattern, it’s terrible and really creepy…. I was just having a discussion with my son about this, and psychologically, if it happened… it’s sort of compartmentalization.”

In deploying a word that gained currency in the late 1990s during President Bill Clinton’s Monica Lewinsky adventure and subsequent impeachment, Whitaker is talking about Cosby—not about himself as a biographer. Cosby: His Life and Times—despite some original reporting on Cosby’s marital infidelities and other human flaws—is essentially a celebration of a socially conscious cultural icon.

The Cosby that emerges from the pages is an admirable artist/activist who has suffered terrible tragedy—the racially charged murder of his only son—but has had a positive impact on race relations in America.

Of course, Bill Clinton—who today is among the planet’s most admired public figures—was only 54 when he left office and has spent the last 13 years relentlessly replacing a reputation for womanizing and worse with public-spirited philanthropy and other good works.

“It’s a little different, because Cosby is 77 years old. He’s almost blind,” Whitaker says, though perhaps there’s still a path to rehabilitation. “There might be an Oprah interview or something like that. There are things you can kind of imagine… Maybe he could suck it up and make amends by giving a whole bunch of money to anti-sexual-abuse causes or something… He still has a fan base. I think people will still turn out for him… If he can’t continue to perform, that will be the hardest thing for him. But if he can still go into arenas, and people will come and laugh at his stories, then he’ll survive. That’s what he’s always cared about the most.”

In this weirdly perverse age of undeserved celebrity and adulation, where Baltimore Ravens fans show up at the stadium wearing Ray Rice jerseys and even Charles Manson can find love and marriage, it’s hardly a stretch to believe that Cosby, too, can reinvent himself.

Yet Whitaker adds: “He’s paid a big price… The show [a planned NBC sitcom] has been yanked. The reruns of The Cosby Show have been taken off the air. He’s routinely called a rapist everywhere. That’s a big price.”

A former editor of Newsweek (years before the newsmag’s brief merger with The Daily Beast), Whitaker also seems to have paid a price. Although his book was generally well-received—with maybe a few tut-tuts over his choice to skip the nastier bits—he is clearly discouraged, even anguished, that it has been overtaken by a tsunami of disastrous Cosby-related publicity.

It’s safe to say that the revival of ugly stories about Cosby’s alleged habit of taking advantage of vulnerable young women impressed by his power, wealth, and celebrity—a fresh round of old charges that, Whitaker acknowledges, the widespread media attention for his book may have partly provoked—is not helping sales.

“It started out quite strong, it was on the bestseller list, and then it kind of fell off a little bit but was still doing OK,” Whitaker says of the two months since Cosby’s publication. “It’s fallen off a little bit more since then. That’s what happens with books these days.”

So far 16 women, including seven who have come forward in press accounts using their real names, are accusing the beloved comedian/father figure/role-model of inviting them to one of his homes or hotel rooms and then drugging and assaulting them.

These are well-known accusations, firmly established on the public record, dating back at least to March 2005, when a young woman named Andrea Constand, the former director of operations for the women’s basketball team of Temple University (Cosby’s alma mater), filed a lawsuit claiming that during a visit to his home in Cheltenham, Pa., to seek career advice, he gave her “herbal” pills, “touched her breasts and vaginal area, rubbed his penis against her hand, and digitally penetrated” her.

Constand’s lawyer produced several other women who were willing to testify under oath to similar encounters, and Cosby, while his legal team denied the charges, settled out of court to preempt a trial.

“I wasn’t going to reprint the allegations. I had a couple of reasons for that,” Whitaker says. “You can do that and say here’s an allegation, and here’s a denial, but given the nature of the allegations, the allegations would stick. As a biographer, you’re really trying to say ‘I’m painting a scene for you. Here you are in the room. This is what happened.’ And if you do enough reporting, you can actually do that. And if you can’t do that, you don’t do that. When you’re writing a book, you want to make sure it’s really accurate, that you can stand behind it, because once it’s out it’s not like a piece in a newspaper or even a news magazine that you can correct quickly. That was just the standard I used.”

In the case of the Cosby charges, Whitaker says he was unable to establish independent confirmation—and because Constand’s lawsuit was settled, a trial record didn’t exist—so the story would have been “he said, she said” and not up to Whitaker’s standards.

“I certainly would not have anticipated the degree to which this has become a huge issue again,” he says. “What you eventually learn about everything related to these allegations, and how you think that should figure in your ultimate judgment of Bill Cosby has to be weighed—and should be weighed—in the balance with a lot of the stuff I reported in the book more thoroughly than anybody else.”

But if Cosby actually did the things he’s accused of, I tell Whitaker, his wholesome image is a carefully constructed lie, and it sounds like he’s a pretty bad guy.

“Or capable of pretty bad things,” Whitaker corrects. “He wouldn’t be the first.”