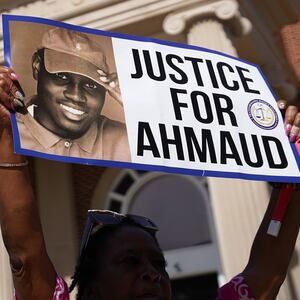

For almost three weeks, scores of Glynn County, Georgia, residents have been questioned during jury selection in the trial for the three men charged with murdering Ahmaud Arbery last year.

Throughout the messy process, potential jurors have told Chatham County Superior Court Judge Timothy Walmsley they already had strong opinions about a case that captured nationwide attention—or else were terrified about rendering a verdict that might have social and legal consequences on the community.

On Wednesday, the government challenged the racial makeup of the jury in the case against Gregory McMichael, his son Travis, and their neighbor William Bryan, all white men. The trio face multiple charges, including felony murder, after allegedly chasing Arbery, a 25-year-old unarmed Black man—whom they said they believed to be involved in a string of break-ins—down before Travis McMichael ultimately shot him on camera.

Specifically, senior Assistant District Attorney Linda Dunikoski filed a “reverse Batson” challenge immediately after the pool of jurors was tentatively finished, alleging that the defense used 11 of their allotted peremptory strikes on Black potential jurors in an act of “racial discrimination.” The challenge was rejected by Walmsley late Wednesday.

The dispute marks the latest obstacle in the case that was always going to hinge on allegations of racial animus—and now features an unsuccessful appeal by way of a procedure one expert called “unusual,” if not exactly without precedent amid a national reckoning on race in America.

“The defense struck these jurors… because of racial bias,” Dunikoski said in her argument for the reverse Batson challenge. A traditional Batson challenge is often used by the defense to argue prosecutors are stacking a jury of white people against a suspect of color, whereas the prosecution was employing the procedure Wednesday in hopes of making a jury more diverse.

Breaking down her argument that defense attorneys purposefully were “discriminatory” with their strike choices, Dunikoski said she was going to “rely on the math.”

“The defense was given 24 strikes, the state was given 12 strikes,” the prosecutor said, noting that before the tentatively final 12-person jury panel was selected, “we had 12 African American jurors…[and] 36 white jurors.”

“So African American jurors made up one-quarter of the jury panel. But the actual jury that was selected only has one African American male on it. It has 11 white people on it,” she said.

Dunikoski went on to argue that the defense “disproportionately” chose to boot out 11 Black jurors in their final striking decisions.

Judge Walmsley quickly ruled there was enough initial evidence to warrant a look and agreed to hear arguments about several jurors the defense struck. They included one woman the defense argued “had a very favorable view of Ahmaud” and another male who was a former police officer and veteran.

Another potential juror struck by the defense wrote on her questionnaire that Arbery was shot “due to his color,” the defense said.

For former federal prosecutor Neama Rahman, the push for a more diverse jury pool is critical for the prosecution in order for them to win this case.

“If the defense is indeed using racially motivated peremptory strikes to whitewash the jury, that is both unlawful, especially unconstitutional, and unethical,” Rahman told The Daily Beast. “Normally, it is the defense who raises Batson motions, but as we saw in the Derek Chauvin trial, the prosecution can use it when the victim is African American. And in the Chauvin case, the state’s effective use of Batson challenges resulted in a jury that was half people of color, which convicted the white aggressor.”

But Laura Hogue, an attorney for Gregory McMichael who spoke on behalf of the defense, argued on Wednesday that race was not the reason they used several of their strikes on Black jurors. Instead, she said, the defense simply had to “rate the best of the worst” potential jurors.

“It was the epitome of the lesser of two evils,” Hogue said, claiming that most Black jurors were struck for having strong opinions about the case or the defense’s clients.

Throughout the trial, the defense is expected to argue that the trio of white defendants was attempting to detain Arbery under the state’s since-neutered citizen’s arrest law. Prosecutors, meanwhile, are expected to cite what they claim is evidence that Travis McMichael used a racial slur at the time of the shooting. Federal prosecutors have already filed separate hate-crimes charges against the three defendants.

“We have a very clear selection process within the defense team, and the issue of race is not one of the factors. I can give you a race-neutral reason for any one of these,” Hogue added.

After hearing the arguments from the prosecution and defense, Walmsley said that while he did find evidence of intentional discrimination in the panel during the strike process, he had to deny the reverse Batson challenge because the “very limiting” statute makes it hard for him to discredit the defense’s strike reasonings.

The judge, however, later stressed that “this case makes it difficult because race has been injected into this process.”

J. Tom Morgan, a former DeKalb County district attorney, told The Daily Beast on Wednesday that he was not surprised at all by the prosecution’s last-minute legal move.

“How can you get a fair and impartial jury in Glynn County?” after the impact Arbery’s case has had there, he wondered.

Regardless of the final jury composition—members of which are unaware of the sparring on Wednesday—the optics of the prosecution already accusing the defense of racial bias in an inherently divisive case were “terrible,” Morgan argued.

“If there is an acquittal or hung jury, there will be allegations of racism, and who knows the public’s response,” the ex-prosecutor added. “That’s why they needed this case to be out of Glynn County.”