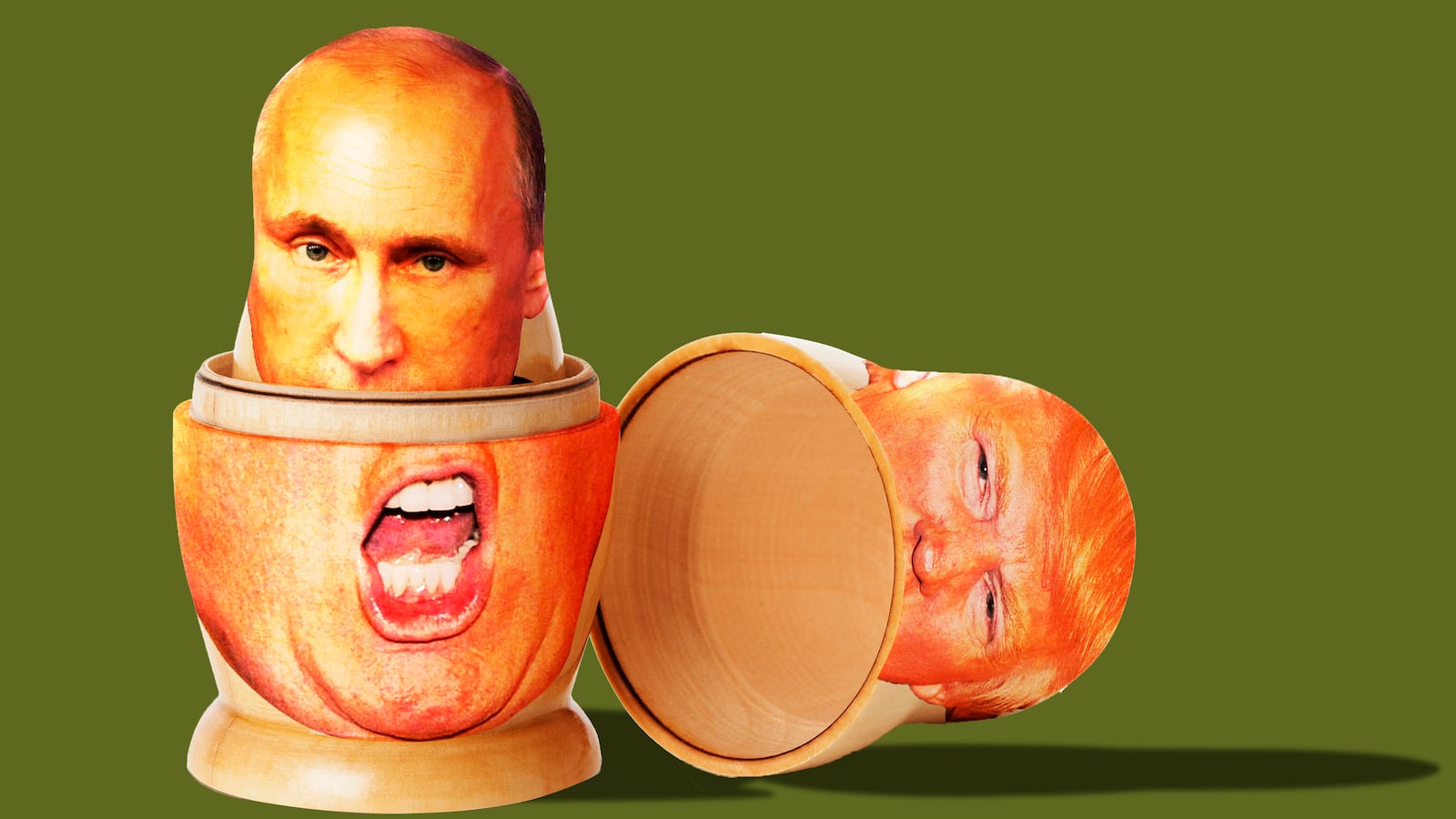

Donald Trump knows absolutely everybody but can’t remember their names or faces, especially when they’re in trouble, and even more so when their mother tongue is Russian. Last month Congress began its inquiry into whether or not the president committed an impeachable offense (or offenses) by withholding U.S. military aid to Ukraine until Kyiv agreed to dig up dirt on his likely rival for the White House in next year’s election. Since then, America has grown acquainted with enough characters from the post-Soviet mob milieu to fill the Star Wars cantina.

Some are newcomers to Trumpland, thanks to the tireless efforts of Trump’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani, whose legal reputation has swung pendulously from that of latter-day Eliot Ness to bug-eyed conspiracy theorist more at home with low-rent Ukrainian Capones. But many of these scrofulous figures are familiar from their prior appearances in the two-year-long Mueller investigation. Russian oligarchs, bankers and two-bit grifters featured more often in that doorstop report than suspected or probable spies. That was surely no accident.

Since the late 1970s, when Donald J. Trump, the scion of a racist slumlord from Queens, washed ashore on the island of Manhattan desperate to put his name on everything and dip it all in gold, The Donald has surrounded himself with a certain track-suited species of clientele from Brighton Beach.

These figures, as we now know, were part of a broader nexus with a marked affinity for Trump properties that helped him regain his losses after a series of bankruptcies threatened his wealth. Time and again, Trump and his business relied on the shady ties detailed below to expand his company’s fortune—and eventually land him enough wealth, and enough clout, to launch a successful 2016 bid for the American presidency.

Trump’s favorite kind of immigrants have a common life story. They came to the land of opportunity from some former Soviet Socialist Republic with barely two kopecks to rub together. They then amassed enormous fortunes either through opaque business practices or completely unknown means. Some have rap sheets and did time; others wound up living in Trump Tower, if not living it up at one of the president’s many bankrupted casinos or resorts. Still others have tried to help Trump erect glittering and gaudy monuments to himself, from Fort Lauderdale to Moscow, only to fail miserably.

All, however, have boasted about their warm personal or professional relationships with the celebrity mogul turned commander-in-chief, even if the favor hasn’t always been returned. And every one of them has alleged connections, either directly or through their own dubious associations, to Russian organized crime—which they categorically deny.

To make things easier for laymen and specialists alike, The Daily Beast has compiled sketches of what we’re calling The Donald’s Dirty Dozen. Many of these ties were first unearthed and detailed in a seminal work from investigative journalist Craig Unger, whose House of Trump, House of Putin remains the go-to book on the topic.

In the past 18 months, Unger’s index hath runneth over as still new underworld-ish no-good-niks have stepped into the light, professing their love for a president who doesn’t remember being photographed with them.

Below are the connected businessmen, alleged fraudsters, con men, racketeers and mobsters implicated in Donald Trump’s long career who snuck out from the wrong end of the Iron Curtain and, whether by accident or design, discerned that special it-factor in America’s own budding oligarch, the very quality that would one day catapult him all the way into the White House.

There’s one name that consistently hangs over all of the discussions of the globe-trotting Russian mafia: Semion Mogilevich, and while there is no evidence he and Trump ever met face to face, there are multiple connections that lead back to him. Think of him as the spider at the center of the web, or the drain that sucks everything in, especially money.

Originally from Ukraine, Mogilevich has gone by many titles. To some who’ve written about him, he’s the “most dangerous mobster in the world,” a title earned by the litany of deaths that have followed in the wake of his exploits across the post-Soviet space, centered on controlling dubiously obtained natural gas pipeline contracts in the region.

He’s also been called the “Brainy Don,” a sign both of his previous history as an academic focused on economics and his deep acumen when it comes to all things money laundering. Indeed, few mobsters, Russian or otherwise, have managed to rival Mogilevich’s repertoire of money laundering skills. As Craig Unger wrote, Mogilevich “mastered a skill that was deeply coveted by the most formidable gangsters on the planet: He took dirty money and made it clean.”

But to the FBI, there’s a different title for Mogilevich: the “boss of bosses,” the man reportedly pulling the strings on an international web of arms smuggling, human trafficking, and contract killings. For years, Mogilevich has been the highest-ranking mobster on the FBI’s most-wanted list, and from 2009 to 2015 even spent time amid the FBI’s Top 10 Most Wanted, alongside Osama bin Laden and Whitey Bulger.

His placement in that roster stems directly from his role in defrauding thousands of investors, including Americans, out of over $150 million. According to the FBI, Mogilevich controlled a Pennsylvania-based company called YBM Magnex International, pumping up its share price after its 1994 inception some 2,000 percent “due to bogus financial records Mogilevich created, bribes to accountants, and lies told to the Securities and Exchange Commission officials.”

The FBI discovered that Mogilevich’s money laundering network spanned 27 countries. “Victims don’t mean anything to him,” one FBI agent said in a statement. “And what makes him so dangerous is that he operates without borders.”

Mogilevich eventually was arrested in Russia in 2008 on tax evasion charges—but was promptly released shortly thereafter. Ever since, the Brainy Don has been living openly in Putin’s Russia, unconcerned about arrest or extradition.

Mogilevich, of course, has denied all of the American charges; he’s even denied that the Russian mafia plays any role whatsoever in the United States. “How can you say that there is a Russian mafia in America?” he once asked. “Where are the connections with the Russians? How can there be a Russian mafia in America? Where are their connections?”

While there’s no evidence Mogilevich and Trump have ever met in person, the Russian godfather’s paw-prints can be found on a number of people with whom Trump has done business in the past.

For instance, David Bogatin (more below), alleged to have used Trump properties for money laundering, was connected directly to Mogilevich’s YBM scam, with Bogatin’s brother helping run the $150 million scheme. Mogilevich also worked closely with Dmytro Firtash (also more below), who admitted he “needed Mogilevich’s approval to get into business in the first place.”

Many of the most well-known Russian or Soviet figures of the past few centuries can point to a time spent in the Siberian prison camps as evidence of their dedication to their respective causes. Dostoevsky, Lenin, and Stalin all plotted and planned while confined to internal exile in the Far East. So, too, did at least one entry on the litany of links between Trump and the Russian underworld: Vyacheslav Ivankov.

Ivankov’s crimes were, at least, clear. Per Soviet authorities, Ivankov gleefully partook in robbery and torture, crimes that slapped him in part of the crumbling Soviet Union’s prison system where it was hoped he could be prevented from wreaking any more carnage. Semion Mogilevich, however, had different ideas. In late 1990, shortly before the Soviet Union collapsed entirely, the boss of bosses bribed a Soviet judge to spring Ivankov, who became the muscle to Mogilevich’s brains.

Ivankov had an important mission: he was to go to America and organize and expand Russian mafia operations on the soil of the world’s only remaining superpower.

Ivankov, by all accounts, approached his task with enthusiasm. Arriving in the U.S. in 1992, he quickly rose through the ranks of the Russian vory, or criminal class, swelling the extortion rackets in Brooklyn into a globe-spanning network. Building on Mogilevich’s talent for money laundering, Ivankov became perhaps the leading godfather of U.S.-based operations.

For years, however, the FBI couldn’t track him to his lair. They knew he was recruiting Soviet veterans from the Afghan War to help lead contract killings, and that he was transforming Russian organized crime from small-scale operations into a global business. But they couldn’t locate his headquarters until they finally found out where he’d been living the whole time: in Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue.

Ivankov was arrested in 1995 but only extradited to Russia on an outstanding murder charge in 2009. His luck ran out once he got home. That same year, he was shot dead by an unseen sniper in Moscow. His funeral, according to those who attended, would have made the screenwriters of Analyze This! roll their eyes.

A decade on, no evidence has ever emerged that Trump and Ivankov, his tenant, met directly. But the fact that the face of Russian organized crime in the U.S. selected Trump Tower as his base of operations remains indisputable.

When Vyacheslav Ivankov arrived in America, he developed a network of yes-men and enforcers, and those who would help launder the money he and his crew would soon be raking in. In stepped Felix Komarov. Komarov emigrated from Russia at the same time as Ivankov, building up a multi-million-dollar art and jewelry business, tapping into Russia’s post-Soviet cultural scene. Along the way, as the New York Times found, he started a Rolls Royce dealership in Moscow and picked up a series of partners who caught the FBI’s attention.

As Unger noted, by the mid-1990s the FBI had named Komarov as an official associate of Ivankov. The FBI’s European counterparts went a step further in unearthing links between Komarov and Ivankov. “In an affidavit in support of a wiretap application in the Ivankov investigation in 1995,” according to the Times, “Lester R. McNulty, an FBI agent in a squad formed to combat Russian organized crime, quoted German law enforcement officials and unnamed informers as stating that Mr. Komarov was laundering money for Mr. Ivankov and that Mr. Ivankov and two associates owned three-quarters of the Moscow Rolls-Royce dealership as a front to launder criminal proceeds.”

Komarov admitted that he may have been in contact with Ivankov, but denied partaking in any money laundering operations. Komarov was never charged in any of Ivankov’s schemes, but he never denied his place of residence, Trump Plaza, on Third Avenue. And he was never especially vocal in trying to distance himself from the Russian mafia. As he said when questioned about his Russian mob ties in 1998, “Hmf, Mafia! If they work like I do 24 hours a day, it would be a good thing.”

Komarov wasn’t the only luxury goods merchant filling out Trump’s ties to the Russian underworld or who, like Ivankov, met with an untimely end. Eduard Nektalov, originally from Uzbekistan, made a living peddling diamonds in New York. Like Komarov, he also came under the scrutiny of American authorities. While his ties with Ivankov weren’t as pronounced as Komarov’s, Nektalov was nonetheless targeted by the Treasury Department in 2003 as a key player in an alleged money laundering ring cleaning Colombian drug money.

At that time he was also dumping millions of dollars into yet another Trump property, Trump World Tower, in midtown Manhattan. (Nektalov picked up a unit in the building that happened to be directly beneath future presidential aide Kellyanne Conway.)

Rumor soon got around that Nektalov was considering cooperating with the Treasury Department, and it didn’t take long for the wrong people to notice. In May 2004, an unknown gunman murdered Nektalov on the street, shooting him three times before walking away down Sixth Avenue, as if nothing happened. As one associate said afterward, “You don’t get shot once in the head and twice in the back in broad daylight for no reason.”

David Bogatin was still another New York resident, a Soviet military veteran who made his fortune running a network of gasoline bootlegging in Brooklyn, setting up a series of dummy gas distributors to hide his schemes. He was also a known Russian organized crime figure, per a 1996 Senate investigation, and an early ally of Mogilevich. Looking for a place to park his money, Bogatin turned to Trump Tower, buying five luxury condos in 1984 in a closing personally attended by Trump. Millions of Bogatin’s dirty rubles went directly into real estate transactions that enriched the future president, with no questions asked.

As it is, that investment didn’t last long. In 1987, a few years after the purchase, Bogatin was arrested and pleaded guilty to bootlegging gasoline. His apartments were seized, and he promptly fled the U.S., but not before jump-starting a pattern that would play out time again between dirty post-Soviet money, Trump’s properties, and Trump himself.

An early transplant to Little Odessa, Felix Sater has enjoyed one of the strangest trajectories of any Russian satellite in the president’s orbit. From jailed Wall Street bar brawler to a convicted racketeer to a CIA agent to a “senior advisor to Donald Trump,” as proclaimed on a decade-old and much-flaunted Sater business card.

That latter function seems to have been the result of Sater’s management of the controversial Bayrock Group LLC, which Sater joined in 2001 and which helped develop, among other properties, the Trump International Hotel and Tower in SoHo. (In reality this building, a failed venture that eventually was resold, only licensed the Trump name in exchange for paying the Trump Organization 18 percent of the profits.)

In a video court deposition in 2013, Trump said of Sater, with whom he’d been photographed, “I really wouldn’t know what he looked like. I don’t know him very well, but I don’t think he was connected to the mafia.”

He was. According a 1998 indictment filed in the Eastern District of New York, Sater and his co-defendants engaged in a “pump-and-dump” stock scheme that defrauded some $40 million from investors. Four separate Italian crime families — Bonanno, Colombo, Gambino and Genovese — were entangled with this financial scheme, to which Sater pleaded guilty. He received a $25,000 fine but no prison sentence.

This was because Sater became a U.S. government informant, tasked with going after the very mobsters he’d colluded with, plus the very jihadists who would soon become America’s foremost national security thread.

As The Daily Beast reported in August, based on newly unsealed court documents, Sater “spent years working hand-in-hand with the CIA and the FBI to target New York organized crime families and Al Qaeda,” tromping through Central Asian countries seeking intelligence on the Taliban, its main opposition movement, and the whereabouts of a number of Stinger anti-aircraft missiles left over from the CIA’s covert war against the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Sater was hailed by federal prosecutors as a brave and compliant cooperator, responsible for securing the conviction of Frank Coppa, Jr., a captain in the Bonanno crime family, who’d been implicated in Sater’s 1998 pump-and-dump fraud.

There’s a Mogilevich thread, too, which runs through the YBM Magnex fraud. Sater allegedly acted as one of the boss of bosses’ main American liaisons, a role Sater has vehemently denied. “I testified before the House Intelligence Committee, the Senate Intelligence Committee, and the Senate Judiciary Committee that the only relationship I had with Mogilevich was helping the FBI figure out the scam in the YBM Magnex deal,” Sater claimed. “The whole thing between Mogilevich and me is a lie, a fallacy, a falsehood.”

Proving that there are third and possibly fourth acts in American life, Sater cropped up in 2017 as one of three architects of a dubious Ukraine “peace” deal presented to national security adviser Michael Flynn, who would not last long in the job. One of the other architects was Michael Cohen, Trump’s longtime personal attorney, who is now serving three years in prison for campaign finance violations and lying to Congress. In 2015, Sater had emailed Cohen, “Our boy can become president of the USA and we can engineer it,” referring to Trump. “I will get all of Putins [sic] team to buy in on this, I will manage this process.”

In November 2013, when Trump traveled to Moscow to host the now-notorious Miss Universe pageant, a conspicuous face joined the other high rollers and suspicious figures populating the VIP section. Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov may not be a household name in the U.S., but to the FBI, he was immediately recognizable. After all, in 2011 Tokhtakhounov had joined Mogilevich on the FBI’s Top 10 Most Wanted, described as a “major figure in international Eurasian organized crime” engaged in “drug distribution, illegal arms sales and trafficking in stolen vehicles.”

There’s also one event that Americans may remember: fixing the ice skating results of the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics. The man allegedly responsible? Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov.

So Tokhtakhounov’s presence at Trump’s most spectacular Russian gala was concerning enough. But 2013 also saw another, far more obvious linkage between him and Trump. That April, American agents rushed into an apartment in New York’s Trump Tower, arresting nearly 30 suspected members of a massive international gambling ring. At the center of the ring was Tokhtakhounov, who remains at large.

Per the resulting indictment, Tokhtakhounov was a vor, a Russian crime boss, with “substantial influence in the criminal underworld” and millions of dollars made in profits per month, via networks of offshore accounts. “I am not bad, like you think,” Tokhtakhounov would later tell the New York Times. “I am not the Mafia, I am not a bandit.”

“Never, never,” insisted Semyon (“Sam”) Kislin when confronted in 1999 with a written FBI allegation that his commodities trading firm was a massive laundromat operating at the pleasure of the Russian mob. The man who moved in the 1970s from Odessa to its diminutive sister port city in Brighton Beach is full of such denials of wrongdoing and points to the fact that he’s never been charged with any crime. He’s a “kosher” businessman who just happens to have once associated with the rough-and-tumble Soviet diaspora that New York glitterati, including his two friends Donald Trump and Rudy Giuliani, can’t get enough of.

Kislin first made Trump’s acquaintance in the late 1970’s when his electronics store in Brooklyn — once a veritable Crazy Eddie for Soviet Foreign Ministry types and KGB agents alike — sold Trump’s Grand Hyatt Hotel 200 televisions on credit. He then offered mortgages to any number of fellow emigres from the East who wanted to park their newfound wealth in New York’s real estate market. And especially in buildings owned by the Trump Organization.

Kislin wasn’t just into American commerce; he also dabbled in local politics. He admired Rudy Giuliani so much in the 1990s that he hosted a fundraiser for the then-mayor’s re-election at the swank Brooklyn eatery Lido. He also co-chaired a major donor bash, which took in $2.1 million, at the Sheraton New York Hotel and Towers for Giuliani’s failed 2000 Senate run against Hillary Clinton. (Kislin donated to a host of Empire State pols, including Senator Chuck Schumer.) His generosity to Giuliani evidently was returned with a seat on the New York City Economic Development Board.

While it’s true that Kislin has never seen the inside of a jail cell, he’s certainly merited the scrutiny of not one but two major law enforcement agencies. As reported by the Center for Public Integrity, which ran in-depth coverage of alleged Russian mob work in the 1990s in New York, a 1994 FBI intelligence report named Kislin as a “member/associate” of what was then the largest Russian organized crime syndicate in the United States, headed by the aforementioned Vyacheslav Ivankov, who lived in a luxury condo in Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue.

Kislin’s Trans Commodities, Inc., meanwhile, employed two Uzbekistani siblings—and alleged gangsters—Lev and Mikhail Chernoy, who were “suspected of money laundering, embezzlement of funds, contract killing,” according to Interpol. The Russian government has accused them of defrauding the country’s central bank of $100 million, then using the money as seed capital to launch their own offshore business empire focused on Russia’s lucrative aluminum industry. Quite a number of the Chernoys’ competitors were subsequently killed in what the Russian press dubbed “the aluminum wars” of the 1990s.

One of the Chernoys’ acknowledged friends was the Russian hit man, Anton Malevskiy, who had worked for the Moscow-based Izmaylovo crime family before dying in a curious skydiving accident in South Africa. Trans Commodities, Inc. and Blonde Management Corp., another New York-based company, chaired by Kislin’s nephew, even co-sponsored Malevskiy for a U.S. visa.

Despite this, Kislin has nothing but fond memories of his former commercial associates. “Mikhail Chernoy is the best man I ever had as a partner,” Kislin told the Center for Public Integrity in 1999, while allowing that Chernoy might have been the one to forge his signature on a Russian assassin’s visa sponsorship form.

Donald Trump met Tevfik Arif in the midst of the Trump SoHo negotiations. Arif, a native Muscovite, was the founder of Bayrock Group, LLC, a company that in 2002 moved into the 24th floor of Trump Tower, and was managed by ex-con turned U.S. spook Felix Sater. According to an investigation by Forbes, Bayrock was bankrolled by three extremely colorful oligarchs from Kazakhstan, Patokh Chodiev, Alijan Ibragimov and Alexander Mashkevich, known collectively as The Trio; Mashkevich is listed as a financier in at least one promotional booklet put out by the company. (A Bayrock spokesperson denies projects were funded by The Trio).

Yet this is not just any troika of oil-and-gas billionaires; they cut their teeth in the 1990s working in partnership with none other than Mikhail Chernoy, Sam Kislin’s employee at Trans Commodities, Inc. and one of the two Uzbek brothers Interpol alleged were “suspected of money laundering, embezzlement of funds, [and] contract killing.”

Arif seems to have had the most fun of all of Trump’s Dirty Dozen. In 2010, he was arrested by Turkish police who raided the Savarona, a luxury yacht once owned by Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, and charged Arif with leading a high-priced prostitution ring catering to the Russian and Ukrainian uber-rich. Arif was acquitted a year later after the girls onboard who were rounded up (one of them was 16) refused to talk to Turkish prosecutors.

In a 2007 presentation published by Bayrock, all of the soon-to-be-failed Trump projects are listed, from SoHo to Fort Lauderdale to Phoenix but there, on a page marked “Strategic Partners,” is a smiling Arif standing next to the future president of the United States.

Currently awaiting extradition from Austria to the U.S., Dmytro Firtash remains one of Ukraine’s most notorious oligarchs—and, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, an “upper-echelon [associate] of Russian organized crime”— a charge Firtash vehemently denies.

In 2004, Firtash founded one of the largest intermediary gas companies in Ukraine and has often inserted himself and that company, RosUkrEnergo, in the intermittent “gas wars” between Kyiv and Moscow. He was seen as friendly toward the pro-Kremlin side of the Ukrainian political establishment; he supported former President Viktor Yanukovych and feuded viciously with the political figures who emerged after the 2004 Orange Revolution, Prime Minister Yulia Tymochenko in particular, who later became a political prisoner under Yanukovych’s second administration.

One bank analyst quoted by the Financial Times described Firtash in 2014 as having “close ties to Russia via the energy sector, and perhaps even to Putin.” He was certainly popular in the U.K., where he’s thrown around money and influence: a mansion in Knightsbridge, healthy donations to Cambridge University, even the creation of his own cultural outreach arm known as the British Ukrainian Society, which was headed by Robert Shetler-Jones, the former CEO of Firtash’s Group DF. The chairman of the society is Lord Rigby; directors have included members of Parliament with other eyebrow-raising foreign associations.

Firtash was charged by the U.S. Justice Department in 2013 with having overseen a criminal enterprise which paid millions in bribes to both state and central government agencies in India in order to obtain mining licenses.

Then there are the alleged mob ties. He’s accused of working closely with Semion Mogilevich, the so-called “boss of bosses” in the Russian underworld. Firtash, as noted, admitted his close affiliation with Mogilevich in 2008 to then-U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Bill Taylor, who is now a key witness in Trump’s unfolding impeachment saga. Firtash denies any links to any organized crime officials, but the once and current top American diplomat in Kyiv says he didn’t always.

As recorded in a 2008 State Department cable published by Wikileaks, Firtash had sought a meeting with Taylor in Kyiv in 2008, whereupon he “acknowledged ties to Russian organized crime figure Semiyon Mogilevich, stating he needed Mogilevich's approval to get into business in the first place. He was adamant that he had not committed a single crime when building his business empire, and argued that outsiders still failed to understand the period of lawlessness that reigned in Ukraine after the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

Firtash has since denied saying any such thing to Taylor, although his connection to Mogilevich isn’t in dispute. It was codified in a company called High Rock Holdings LLC, which Firtash joined in 2001. For starters, the financial director of High Rock at the time was Igor Fisherman, Mogilevich’s right-hand man and fellow co-conspirator in the aforementioned YBM Magnex pump-and-dump stock fraud. Also, more than a third of High Rock was owned by a separate corporate entity whose director at the time Firtash joined was none other than Mogilevich’s ex-wife. That’s either one hell of a coincidence or proof that Bill Taylor is indeed an excellent note-taker.

The Justice Department certainly seems to believe in Firtash’s organized crime affiliations and has referenced them in connection with his dealings with another shady figure: Paul Manafort. Manafort and Firtash were once partners in an attempt to buy and redevelop the Drake Hotel in Manhattan at a cost of $850 million, $100 million of which would come from one of Firtash’s companies. The deal fell through.

Not that Firtash holds any grudges. He also doesn’t make much of the abortive venture. In an exclusive interview with The Daily Beast’s Betsy Swan, he said he never invested any money in the Drake Hotel project. He also has no hard feelings toward Manafort, reserving his scorn for Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton, who, he said, was given a helping hand with her 2016 election campaign by the U.S. embassy in Kyiv. This is of course a discredited conspiracy theory much beloved by Donald Trump and Rudy Giuliani.

Indeed, although Firtash told The Beast that he believes Trump has a third-grade education and isn’t very bright, suspicions have been aroused that he is quietly helping the White House compile opposition research on Biden and also on the Mueller investigation in exchange for scuttling his extradition. A recent Washington Post story stated that prosecutors in Chicago, where Firtash was indicted, “suspect there might be a broader relationship” between Firtash and Igor Fruman and Lev Parnas, the two Soviet-born figures close to Giuliani who recently were indicted on federal election campaign violation charges.

The links between Firtash, Parnas and Fruman remain some of the most concerning of those recently revealed. According to Reuters, both Parnas and Fruman “worked in an unspecified capacity” for the gas baron, whose reputation in Ukraine has long been a byword for exactly the kind of endemic corruption Parnas and Fruman attempted to instrumentalize in their dealings with Giuliani. Two well-known pro-Trump attorneys, the husband-and-wife team of Victoria Toensing and Joseph diGenova, are now representing the oligarch, and recently hired Parnas as a supposed interpreter. It remains unclear why Parnas was hired, but, as CNN reported, Parnas apparently claimed he was now “the best-paid interpreter in the world.”

It might have been because one of them owned a company called Fraud Guarantee. Or that another ran a beach club in Odessa called Mafia Rave. Or that they were both helping Giuliani, their sometime personal attorney, take disinformation about Joe Biden’s son from notorious former Ukrainian prosecutors. Or that they both look like regulars at Tony Soprano’s Pork Store. Or that they both live in South Florida. …

Whatever the case, cruel nature seems to have decided long ago to make Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman supporting cast members in a sprawling transnational crime saga, one which recently landed both emigres in federal prison as they attempted to travel from their adopted home in the United States to Frankfurt, Germany. First class, natch.

Parnas and Fruman, along with two other defendants, “conspired to circumvent the federal laws against foreign influence by engaging in a scheme to funnel foreign money to candidates for federal and State office so that the defendants could buy potential influence with candidates, campaigns, and the candidates’ governments,” according to their indictment by the Southern District of New York.

Their now scandalized campaign contributions — totaling over half a million dollars, much of it diverted to Trump-affiliated political entities — had once earned them a dinner companion in The Donald, a breakfast companion in his son, Donald, Jr., but most of all an influential business associate and confidante in the former U.S. prosecutor and New York mayor turned conspiracist consigliere to the most powerful man in the world.

According to the New York Times, Parnas “advised Mr. Giuliani on energy deals in the region and pursued his own in Ukraine even as he portrayed himself as a representative of Mr. Giuliani on the Trump-related matters.” Giuliani made $500,000 to consult on “Fraud Guarantee’s technologies and provide legal advice on regulatory issues,” as Reuters further reported. America’s Mayor even took Parnas to John McCain’s funeral.

How did the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of Ukraine-gate strike it rich? Parnas has stated in an interview that he started out selling condos for Fred Trump, Donald’s father, when Fred was the head honcho of the Trump Organization. Then he moved back to the Soviet Union where he got into shipping; then he reinvented himself as a securities trader. Fruman was into jewelry and cars and now runs an import-export business in New York.

“Where Parnas and Fruman got their money,” the Washington Post noted with justified skepticism, “remains a mystery.”

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, in collaboration with BuzzFeed, ably tried to solve it. Parnas, the OCCRP reported, formerly “ran an electronics business that was successfully sued for its role in a fraudulent penny stock promotion scheme. He has also worked for three brokerages that later lost their licenses for fraud and other violations.”

Fruman, meanwhile, is connected to a character in Odessa named Volodymyr “The Lightbulb” Galanternik. Galanternik is an associate of Odessa’s former and thoroughly mobbed-up mayor, Gennadiy Trukhanov, whose wife, Natasha Zinko, is best friends with Fruman’s ex-wife, Yelyzaveta Naumova. Moreover, as the OCCRP found, Fruman and his business partner, the unimprovably named Serhiy Dyablo, control a host of properties in Ukraine including “a hotel, apartment buildings, a series of luxury boutiques,” and the aforementioned Mafia Rave beach club.

Bada bing!

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct a detail about the victims in a stock fraud case to which Felix Sater pleaded guilty and to include a denial from Bayrock that it was bankrolled by three oligarchs known as The Trio.