This color photograph, of a historic garment unseen by the public for decades, shows Amelia Earhart’s kimono-like robe that she wore before taking off on her record-breaking flight from Honolulu to California in 1935. Earhart would vanish two years later on an epic attempt to circle the world near the equator. Only glimpsed in black-and-white photos by most historians until now, the vibrant silk garment once stood in the middle of an ugly controversy, not so different from today’s “fake news” fights, between those who fabricated stories about the beloved aviator after she disappeared and those seeking the truth.

When Amelia Earhart’s last message was heard at the start of July 1937, she had been flying for 20 hours and 13 minutes from Lae, New Guinea, towards a pinprick island in the Pacific Ocean called Howland Island. Earhart had estimated this leg of her highly publicized round-the-equator trip would take 18 hours, so when she sent her last dispatch, on July 2, she was two hours overdue at her target. After that last message—“We are on the line 157-337 flying north and south”—she vanished.

For the next two weeks, the shocking disappearance of Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan dominated headlines in American newspapers. There was extensive worldwide coverage, too, including empathetic news coverage from Japan. Although he held a limited pilot's license, Noonan was not a second pilot on this trip. He was, however, one of the few seasoned navigators of the 1930s Pan Am clippers that flew affluent customers to South America and across the Pacific. In 1937 there was no GPS, of course—it was all just dead reckoning and celestial navigation that relied on Noonan's skillset. Working radio equipment would have helped.

After Earhart and Noonan disappeared, President Franklin D. Roosevelt quickly signed an order allowing Navy Secretary Claude A. Swanson to authorize the most expensive sea hunt ever, involving a quarter of a million square miles of the Pacific Ocean.

The Navy's dragnet was led by Rear Admiral Orin Gould Murfin, commander-in-chief of the Asiatic Fleet. The Itasca, a coast guard cutter that departed from Howland, was at the center of the rescue operation. She was joined by the battleship Colorado. Under full steam, the aircraft carrier Lexington soon followed. As the Lexington left San Diego, the carrier had sixty-two planes on her flight deck, four destroyers, a minesweeper, and a seaplane. With this impressive armada, the military scoured the South Seas for 16 days by sea and air. The desperate search for two civilians was even aided by Japan, not yet at war with the United States. At the end of the 1937 search, it was taken as a given that "America's premier lady flyer" had radio trouble and weak knowledge of Morse code. She had simply run out of gas.

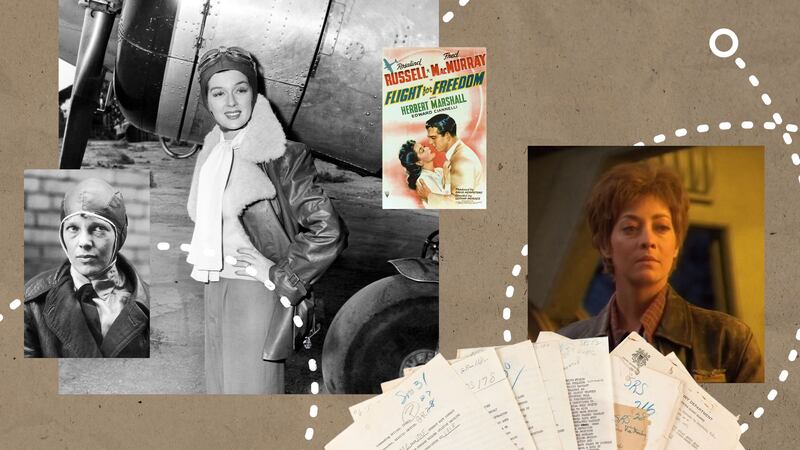

A bit of anti-Japanese propaganda proved "helpful" four years later, after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. To fuel anger, the American government helped along a 1941 fictional Hollywood film about Earhart called Flight for Freedom, starring Rosalind Russell and Fred MacMurray. The original script had been written in the 1930s but rejected as offensive to the Japanese. Now, this fantasy-based storyline about America's "greatest female pilot" was dusted off and greenlit, with the rabid pacifist portrayed as a military spy. Chinese character actor Richard Loo portrayed the Japanese villain, mild-mannered Mr. Yokahata, whose final double-cross caused audiences to boo and hiss.

Anti-Japanese sentiment fueled the 1941 film "Flight for Freedom." Producers insisted the lead character, played by Rosalind Russell, was not a facsimile of Amelia Earhart. In 1995 Earhart was also included in a Star Trek: Voyager episode that also pulled from the myth that the Japanese captured Earhart.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Heritage Auctions, HA.com/EverettProducers, as ever, were eager for a buck, and issued a weak denial—insisting the character obviously based on Amelia Earhart wasn’t based on Amelia Earhart. But some people who watched the movie could not tell fact from fiction. The phenomenon repeated in 1995 when Earhart was included in a Star Trek: Voyager episode. (The one where the Voyager crew found Earhart and Noonan secured in a suspended animation chamber, the missing duo in a mine shaft. Once defrosted, Earhart—played by Sharon Lawrence—told how 400 years earlier, back in 1937, she had been used as a slave laborer on a planet in the Delta Quadrant after encountering a bright light on her famous last flight before losing consciousness.)

The impact of both the wartime film and the 1990s television episode went beyond entertainment. After watching the former, many Americans touched by war formed a "Japs took her" theory. And after that Voyager episode aired, a scientific study found that 4.5 percent of Americans believed she was kidnapped by aliens. That's right.

Bullshit can be stubbornly persistent. Multiple studies have shown that the belief in conspiracy theories is significantly associated with lower self-assessed intelligence, greater political cynicism, and lower self-esteem. Some psychologists indicate that people use conspiracy theories to make sense of tragedies. Humans are predisposed to see ambiguous events as the result of someone's intentions rather than a mere accident.

There are those, of course, who can make good money off ambiguity.

One day in the late 1960s, a seasoned pilot named Elgen Marion Long read an opportunistic CBS newsman's 1966 book called The Search for Amelia Earhart. Despite contradicting military intelligence and family members' insider knowledge, the author, Fred Goerner, claimed that he alone had solved one of America's greatest mysteries. Another would-be historian, Paul Briand, a military man, had tried to capitalize on her disappearance earlier in the decade. His smaller book ended with explosive information-for-pay offered by Maximo Akiyama and his wife Josephine Blanko, the “native assistant” of a New Jersey dentist named Dr. Casimir R. Sheft. Josephine claimed to have seen Amelia in Saipan, in the summer of 1937, when she was 11. Their aggressive lawyer William Penaluna wanted “fair play” from young Briand, i.e., good monetary compensation for his client’s outrageous claims. As an older and skilled pressman, Goerner easily secured a more prominent publisher, and could draw special attention to his own bunk.

And what was that bunk? In 1937, when Earhart and her navigator Noonan disappeared around the equator, Goerner proposed they had crash-landed. According to him, they were captured and executed by the Japanese because they were spies.

News outlets eager for ratings reported his grossly inaccurate (and racist) theory.

One man wasn’t buying it. And that man’s resume was hard to beat. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in high school, Elgen Long left school in Oregon to enlist in the Navy at 15. He trained as a radioman and did 100 missions as a bombardier and navigator. He was honorably discharged as a U.S. naval officer in January 1946, after 3 1/2 years of service. After the war, he enrolled at the University of Southern California's aircraft accident investigation program on the GI Bill. In 1947 at the tender age of twenty, he was hired by the Flying Tiger airline, where he spent 40 years as a pilot, radioman, navigator, and instructor. He was also part of a storied secret mission to airlift the ancient Jewish Yemenite community to Israel. In 1957, he became an accident investigator for the U.S. Pilots Association. As a side gig to his piloting, he led 40 years of air safety investigations.

Elgen Long—who died in Reno, Nevada late last year, just short of his ninety-fifth birthday—was the real thing.

After a few eye rolls, Long put down Goerner's book and spoke to his wife. This book was garbage! He had even been on patrol on Howland Island, where Amelia Earhart disappeared. During World War II, Long had been a young navigator aboard Navy patrol bombers and had spent four months on Saipan between July and December 1937.

Amelia Earhart in a Japanese restaurant in Hawaii wearing her yellow silk kimono before taking off on her record-breaking flight from Honolulu to California in 1935. Elgen Long, right, helped investigate the disappearance of Earhart.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Matson Archives/Heritage Auctions, HA.com/AlamyWhen Goerner wrote that Amelia Earhart's plane was found in a hangar by Americans, Long almost threw the book at a wall. The notion that a hangar was still standing after the Battle of Isley was folly. (Isley was the name given to the Saipan airfield after it was captured by the Americans in July 1944.) As the World War II navigator and bombardier remembered it, there wasn't a single blade of grass left on Saipan by then. Saipan had been littered with Japanese engine parts from his stay on the island. Wishful thinking, indeed.

Long was living in San Francisco when on November 5, 1971, he started out on his own record-breaking ambitious world-girdling flight. That year, as a prematurely graying 44-year-old, he flew over the poles in a twin-engine light plane called a Piper Navajo. Compasses did not work at the North Pole, and he had to use celestial navigation. There were fuel stops where he would catch much-needed sleep; the fuel tanks in the plane could keep him flying for 24 hours.

This 30,000-mile pole-to-pole flight, known as the Crossroads Flight, broke multiple records, and he made the first solo flight over Antarctica. He was the first to fly solo from Antarctica to Australia. At the end of the flight, a month after he started, he was met at the runway by 200 people, including his neighbor, former child star Shirley Temple.

After one honor in Paris, his wife joined him for the banquet. After much champagne that evening, he was back in his fancy Parisian hotel, giddy and grateful. "Aviation had been very kind to me," he told his wife. He wanted to give back to the field. But how? Marie K. Long was Elgen Long's loyal and unsalaried promoter and very press-savvy, and she had an idea.

What about once and for all determining how Amelia Earhart's disappeared? Hadn't he said he was appalled at the nonsense being bandied about? Wasn't he the most qualified man for this job?

Was she joking?

Of course not! Long was trained the same way as a navigator back in the day, celestial navigation. He'd had the training that Noonan had, to been taught to think like him, plus his crash investigation history. He had been a fearless pilot who wanted to break records like Amelia. His mindset and skillset matched what Amelia and Fred had been doing, and he was uniquely positioned to figure things out. As a pilot, he could also fly anywhere in the world to interview people.

And he did.

Before the lights went out in Paris, he was sold on his wife's idea. His decision couldn't come at a better time. The peak of the nonsense was a recent book by Joe Klaas that claimed Amelia Earhart was alive and living in Monroe, New Jersey, as Mrs. Guy Bolam. As they explained: Her life had been bartered by Japan so Emperor Hirohito would not be tried as a war criminal. A photo of Amelia in a kimono was included as part of Klaas's evidence, captioned: "Amelia Earhart being served in a Japanese tearoom."

Over five decades, Goerner was the first of many "serious amateur Earhart investigators" who Long would battle, and he was the one who has earned the most respect of the top aviation experts in the country. Long’s credibility was enormous, and he was the leading spokesperson for the theory of reason. The leading aviation museum directors and experts try not to go on record bashing individuals. They find that unseemly and have often been told not to do so. Still, off the record, they gush about Long’s work.

Early on in his Earhart investigations, Long met Amelia Earhart's only sister, Muriel Earhart Morrissey, a teacher and writer living in Medford, Massachusetts, just outside of Boston. As a mom and an active member of her church, she’d lived the good long life her sister had been robbed of. Over many years, she’d desperately tried to steer her sister’s legacy away from her spectacular death, and back onto her achievements. So very many years after her sister had died, she was still swatting away crass opportunists like Briand and Goerner, and it was exhausting work.

Elgen Long’s record-breaking polar flight was all over the news, and she was eager to meet. When he flew himself to Boston, he explained his background in aviation accident investigation and how he planned to give back to aviation without resorting to nonsense. Morrissey was intrigued that such a respected aviator was willing to help, as an older woman telling less dramatic facts didn’t get much traction debunking the stupid.

Even respected journalists like Pulitzer Prize-winning historian William Manchester, who had signed up as a marine right after Pearl Harbor, bought into the Japanese capture nonsense. Even one of my Pulitzer Prize-winning journalism heroes, New York journalist Pete Hamill, drank the racist “Jap capture” Kool-Aid too. (I was slightly crushed when I learned he wrote a never-produced screenplay about her capture by the Japanese for his then-girlfriend, Shirley MacLaine, to star in. I read the script with a frown while sitting in a New York Public Library archive room at Lincoln Center.) Hamill later married a widely regarded Japanese journalist named Fukiko Aoki who thoroughly researched Amelia's disappearance in Japan and found nada. At least Hamill changed his mind before his death.

Elgen Long soon learned that Muriel and other family members were still convinced Amelia had perished in the ocean. He was a man on another mission and soon spent his free time tracking down everyone who knew Amelia or could provide information and flying to other continents if necessary. When he retired from flying in 1988, he’d logged 45,000 hours without accidents.

With more time on his hands, Elgen also joined three expeditions in 2002, 2006, and 2017 run by the team that discovered and explored the Titanic wreck site. To his delight, he was invited in the capacity of advisor.

Long's granddaughter, Marika Pickles, went along on two of these privately-funded expeditions led by David Jourdan. These deep-sea quests relied on Long's research and several other scientific sources. "Out on a ship for two months," Pickles told me by Zoom, “you see nothing but the horizon, and there was a point where we all ran out to look at a plane overhead because it was exciting. But until you are out there in the heat and the equatorial sun, it is impossible to realize just how vast the Pacific is and how isolated this expanse is too. You are just out in the sun in this nothingness."

Understandably, as the crew who recently found the Shackleton ship would agree, you might have to shift your target as you are there, even with the most accurate guess.

Jourdan’s team was disappointed when they did not find evidence of Amelia’s plane on any of their missions, but did not fudge their results.

"There was nothing solid to report,” Pickles said, “but Grandpa was still sure one day she would be found.

“Every time something gets discovered and covered in the media, that part that was disproven is not as interesting. People want to have something to be excited about. You say someone is claiming this. But when it gets proven wrong, that's not exciting to read about. ‘Oops’ doesn't get the coverage."

On July 16, Amelia Earhart enthusiasts will have a shot at owning this kimono in addition to the rest of the world. Heritage Auctions will hold a Dallas live morning auction for 17 rare Earhart items owned by Elgen Long's estate.

Amelia's kimono, radio dispatches and an original oil painting of Amelia by LeRoy Neiman are among the treasures to be auctioned on July 16.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Heritage Auctions, HA.comIn addition to the Earhart archive, there is a slightly overwhelming collection of Coast Guard Itasca radio dispatches, the top copy pages of the Navy archive from July 1-16, 1937. Presidential buffs will enjoy Amelia Earhart's 1935 letter signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt, congratulating her on her solo flight from Honolulu to California. A 1926 navigator's textbook contains her handwritten notes on every page. (She scribbled these notes after getting her license in California and working as a social worker in Boston, wanting to get back in the air.) Or you can buy her fingerprints and even her DNA gleaned from intact seals on the envelopes and stamps? (Experts have indicated that the likelihood that the chance one of the envelopes holds her DNA is an astounding 95 percent.)

For art enthusiasts of a sort, there is an original oil painting of Amelia by LeRoy Neiman. The former Playboy magazine illustrator made notoriously loud and gaudy paintings, and in that regard, this one doesn't fail. His work can sell like hotcakes, and this populist work has an interesting provenance.

As for the kimono, a thank you note to Elgen from Amelia’s sister Muriel establishes that he acquired the kimono in 1979. During a recent visit to Heritage’s headquarters in Dallas, Texas, I’ve had a long look at the letter Morrissey wrote to Elgen to outline what he had in his possession.

The photo said to have been taken during Japanese captivity was in fact taken just before Christmas in 1934, days after Amelia took a luxurious Matson oceanliner, the SS Lurline, from Los Angeles to Honolulu.

Also on the ship were her husband, George Palmer Putnam, the charismatic stunt pilot Paul Mantz (her possibly-Jewish aviation coach—and, oy, there’s even an Earhartworld argument there), and her 1934 mechanic Ernie Tissot. Her bright red Lockheed Vega plane, the second of two she owned, was tethered to the ship’s tennis court deck. In a cabin room on the way over, her posse reviewed her secret flight plan during the five-day crossing. As part of her plan to debunk rumors that she could not fly with skill, she would attempt a risky solo flight from Honolulu to Oakland.

The first time she set foot on the territory of Hawaii was on December 27 at Pier 11. During onshore interviews, she was coy, saying she was in Hawaii for a series of lectures at the University of Hawaii. She added that the Vega would be used for interstate travel. Aviation reporters were suspicious from the moment she touched down. Her Vega's standard fuselage contained 210 gallons of fuel. In any case, the plane had 460 gallons of fuel, enough to fly to California. She did not know when the solo flight would be. While Earhart was interviewing, Tissot and Mantz snuck her plane to Wheeler Field in Waikiki. Tests would be secretly conducted to see if the Vega could handle a brutal Pacific Ocean crossing.

Initially, Amelia stayed at the pink, Moorish-style Royal Hawaiian Hotel for a short period. (This hotel was also built for the Matson lines.) However, her visit there would be brief. But she would dine in the Japanese restaurant of the hotel in the silk kimono she had just bought or was more likely given.

Paul Mantz, Amelia’s aviation tutor, connected to a former high-profile client, 35-year-old Fleishman yeast scion Christian R. Holmes, who offered the group a temporary home at his palatial mansion on Oahu's windward shore. Called "Queen's Surf," the colossal mansion was a hybrid of Greek revival and modern architecture located about 100 feet from the beach on a private island. The wealthy 35-year-old (and thoroughly eccentric) Holmes was known for his elaborate luaus, his private zoo, and a fleet of speedboats. Queen's Surf had 18 Japanese servants, all at Amelia's disposal.

While her plane was being repaired, Amelia maintained that she was here for a casual visit by lecturing and making public appearances. On January 6, 1935, she planted a banyan fig tree in Hilo, a coastal city on the eastern side of the Big Island. It's still there, identified by a wooden plaque.

Amelia took off from Wheeler Field at 4:40 p.m. on January 11. Eighteen hours and fifteen minutes later, she landed at Oakland Airport to a jubilant crowd of 5,000 people. In making a solo trans-Pacific flight, she became the first person of any gender to do so. It was also the first flight in which a civilian carried a two-way radio.

Pickles’ esteemed grandfather always believed a compass error was at play when Earhart's Electra flew in a particular direction. As a result, none of the other parts of the flight were affected. Moreover, he suspected Earhart and Noonan believed they were somewhere they weren't. His opinion would never change. He was convinced that they came within twenty miles of Howland Island and, if they had come within fifteen miles, they would have seen it. Until his last moments, he was convinced that Amelia Earhart's Electra still awaits discovery at that depth because of the lack of light and oxygen.

Would a plane really be intact if Elgen Long is correct? To be clear, nobody (who follows Long’s theory) is sure if it is intact. On the other hand, they know what the weather was like that day. The day was calm, and the ocean was calm like a lake. She was at the limit of her fuel. Close to empty, if not totally empty. This means the plane was very light, and there would be no fire. Aviation experts know how to ditch a plane, which means the landing gear is folded under the belly of the aircraft before wheels up, so the process is smooth. And ditching is relatively easy, so it is a known maneuver. Those who follow what Long said, which is most people I interviewed for my forthcoming Earhart biography, see no reason that the plane shouldn't have been able to land intact. And then it would have flooded relatively quickly. If it took ten minutes or two hours, it doesn't matter. That's fast enough.

"Grandpa was disappointed he did not live long enough to see a plane recovered," Marika Pickles told me. "I know that for sure. We came back without the plane from our last expedition to Howland. He was up there in years and was soon resigned to the fact that the plane would not be recovered in his lifetime. But he was certain at his deathbed that one day it will be found close to where he always expected to be. I'm certain he wouldn't mind seeing his grandchildren carry on the search if they had the inclination. Also, I doubt he would have a problem selling his collection, but he'd turn over in his grave if we did not believe in facts over fiction."

Laurie Gwen Shapiro’s biography of Amelia Earhart will be published next year by Viking Books. She is an adjunct professor of journalism at NYU, and the 2022 winner of the Silurian Press Club’s People Profile award for her New York Times profile on World War II pilot Si Spiegel.