Before West Africa was gripped by an epidemic, before images of abandoned bodies in the streets of Monrovia, before chlorine and quarantines, before CDC predictions of calamity, before the scare in Dallas and talk of closing the border, before the United States deployed the 101st Airborne Division to fight a disease, before Ebola, Liberia was known for its civil war.

By any objective measure, that 13-year slaughter was a human catastrophe: over 10% of the population dead and 80% internally displaced—numbers that dwarf (as if there is some sick contest here) today’s tragedy in Syria. But the 1989-2003 Liberian civil war gained infamy not for the quantitative count of its suffering, but rather for its grotesque headlines; child soldiers fought naked under the tutelage of teenage generals, juju priests in Halloween masks blessed fighters, and warlords tortured and exterminated whole villages.

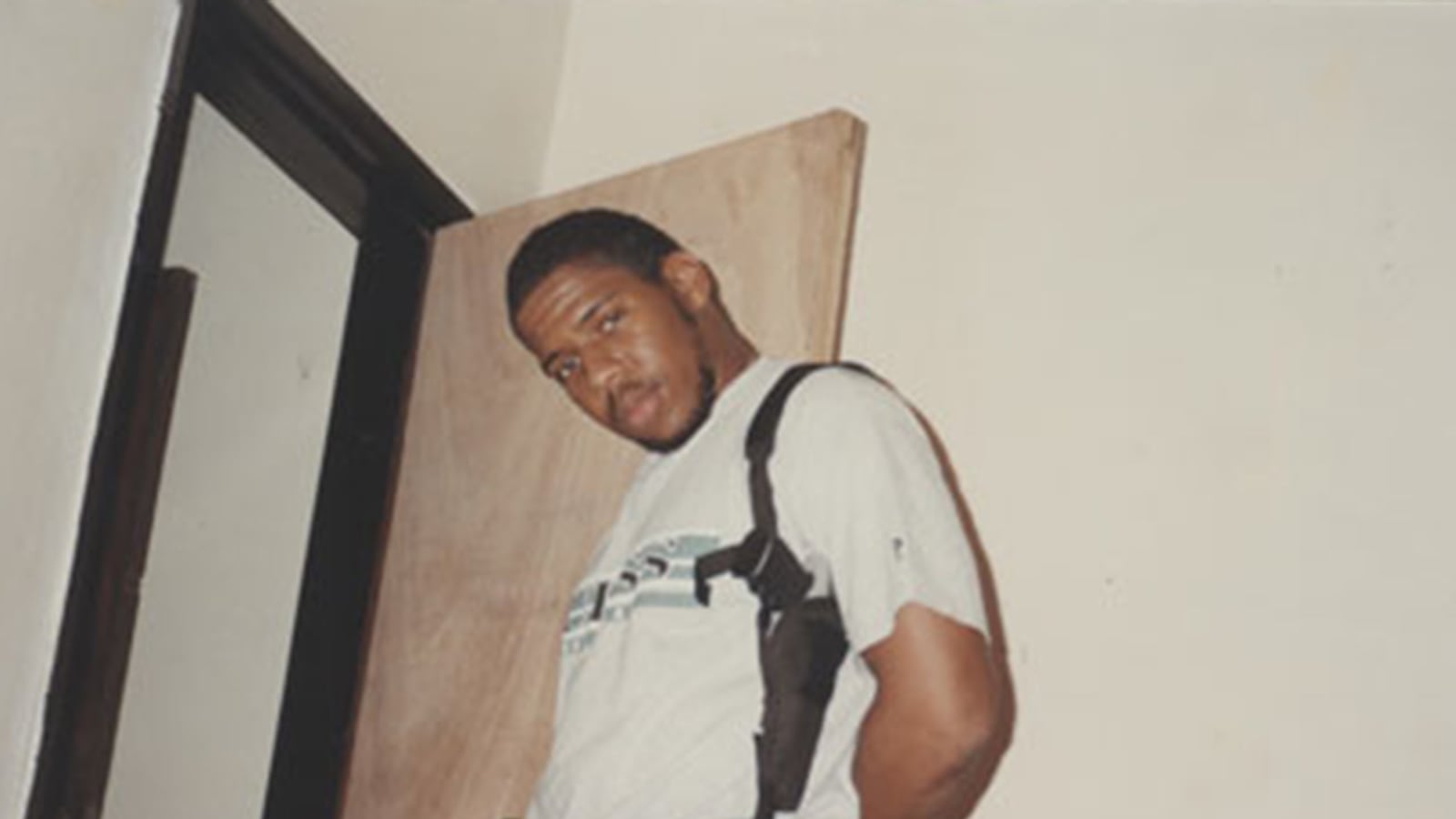

Chucky Taylor was one such sadistic antagonist. The illegitimate son of then-Liberian President Charles Taylor, Chucky nominally led the Anti-Terrorist Unit (ATU), one of his father’s many retinues of bodyguards. To obtain approval and affection, he disappeared his father’s enemies, real and perceived. He beat his subordinates to death, and inflicted pain for sport. For this he eventually ended up in U.S. federal prison, because amazingly Chucky Taylor is an American citizen, the only person ever tried and convicted of torture committed abroad under U.S. law.

Johnny Dwyer’s subtitle for American Warlord, his narrative of the life and times of Chucky Taylor, is A True Story, and not for nothing, as even the basic proven facts of the case might otherwise strain credulity.

Chucky Taylor was born Charles Emmanuel, in Boston in 1977. His mother was Bernice Emmanuel, the daughter of immigrants from Trinidad, his father a young ambitious college student from West Africa named Charles Taylor. The latter eventually returned to Liberia and started a civil war, while Bernice moved to Pine Hills, Florida, and remarried. Chucky’s name was legally changed to Roy Belfast, an attempt to distance him from his biological father, but the name never stuck. By the time Chucky dropped out of high school, he was in trouble with the law and had attempted suicide. In response, Bernice sent him to Liberia in 1994, in the middle of the country’s civil war. “I’ve had him until he’s 17. Now it’s your turn,” she wrote Charles Taylor.

These opening chapters bounce around in time, as Dwyer attempts to intertwine the history of Liberia with the history of Chucky and his father. The result is jumbled, but Dwyer hits his stride as the whole Taylor family comes to participate in the civil war. As one of Chucky’s victims would later recall: “He came as an innocent child and he saw his father in power and they handed him a gun. When he handled a gun, he was happy, he was power drunk. He could do anything when his father was president.”

Chucky is drawn to the violence of the front line, wants to be an action hero like he sees in American movies, and because of his pedigree, he is given a position leading the ATU. The result is disastrous. “Taylor Jr. had no capabilities as anything,” said a South African mercenary who was providing training to the unit. Chucky remains in charge, but it is not clear whether he is really any more than a figurehead, his limited powers extending only to womanizing, drug procurement, and torture. The most horrifying portions of the book detail the treatment of prisoners and recruits at the ATU training center in Gbatala. Chucky has a series of pits dug from the earth, too small for a man to stand or lie in. He calls these pits “Vietnam,” fills them with water and sewage. The poor souls jailed in these have their hands tied above their heads, to metal grates that cover the holes. Sometimes, when the guards are bored, they drip hot molten plastic down onto the prisoners.

At Chucky’s worst, fans of Games of Thrones will note that Dwyer presents him as no more than a diminished and less eloquent version of Prince Joffrey: petty and cruel, killing underlings for no cause, in the shadow of a kingly father who is both more capable and auspicious. By halfway through Dwyer’s book, I found myself rooting for Chucky’s comeuppance.

The fall comes, but not quickly, and not before the story grows ever more bizarre. Chucky flies his former high school girlfriend, Lynn Henderson, to Monrovia for a state wedding. His mother, Bernice, spends more and more time in Liberia as well, taking self-appointed unspecified roles in the government. Chucky leads his ATU to harass American workers at the U.S. embassy in Monrovia, setting up checkpoints outside the main gate. He tries to establish phony companies to siphon off Liberia’s timber and mineral wealth, but is too inept to do more than swindle away some machinery. When rebel warlords finally close in on Monrovia, Chucky flees the fighting, abandoning his post with the ATU on the front line to cower in his father’s bathroom.

The motivations for each of these actions remain opaque, as does Chucky himself throughout this book; while Dwyer provides a few clues here and there, one suspects there isn’t much to discover. In his defense, no one in Chucky’s life comes off well either. Bernice is an opportunist and poor liar. In denying that she knew anything about his longtime military activities, drug addiction, or adultery, Lynn is self-delusional, willfully ignorant, or both; she later refers to the whole episode as her “African princess fairy-tale.” Chucky himself is quoted only a handful of times, mostly in letters to Lynn that Dwyer wall-papers with [sic]’s. The American federal agents who questioned him after his arrest would later find that, as Dwyer writes, Chucky “had no idea how to assemble thoughts into words and was not at all self-conscious of this fact.”

In the end, this arrest and Chucky’s trial are almost accidental. The accusations of torture were uncovered while U.S. Customs and Homeland Security agents were investigating unrelated weapons trafficking using post-9/11 powers. After Charles Taylor is forced from power in 2003, Chucky escaped to Trinidad to become a hip-hop artist. Years later, when he obtains a passport and tries to return to the United States, federal agents are waiting for him; it is the government of Trinidad that finally informs the U.S. that Chucky is an American citizen.

Chucky is charged with torture under a relatively recent law, passed by Congress in 1994 simply to comply with an international human rights treaty. Later, Bush administration lawyers would famously argue that the law did not apply to the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation techniques”; Chucky’s lawyers unsuccessfully used those memos and their national security rationale in his defense. And so Chucky becomes a scapegoat in the original meaning of the term: All of the evils of Liberia’s civil war, and all of America’s torture guilt, get placed on his head at trial. Chucky is serving a 97-year sentence. His father’s sentence from The Hague, for crimes against humanity, is only 50 years. In 2009, Liberia completed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission report on the civil war, but not a single criminal charge resulted from the effort. Chucky stands alone.

Dwyer’s strength as a journalist is clearly archival research, and from the exhaustive footnotes, one sees how he painstakingly constructed his narrative out of court records, diplomatic cables, and Freedom of Information Act requests. It is a major achievement to convert so much disparate material into a coherent story, but this reliance on official documents also gives the book an incomplete feeling; it seems like we only see what was later proven by lawyers at trial. There are large gaps between vignettes, and some established history is skipped entirely. For example, Leymah Gbowee and the women’s peace movement she led, for which she won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011, are not mentioned at all, despite the fact that they were critical to forcing Charles Taylor from power.

The most interesting part of the book, however, may be the Author’s Note at the end. Here Dwyer finally uses the first person, and explains how during his research Liberian villagers would not talk unless he paid them. (Dwyer refuses, and leaves without the story.) He also admits that Chucky would barely speak to him at all, which explains his silence throughout the rest of the text. American Warlord, then, is the sum of what Dwyer could prove with a bumper crop of journalistic ethics and corroborative testimony. This small window into the writing process, recently re-popularized via crime dramas like Serial, makes one imagine the book that might have been written if Dwyer were not so wedded to a traditional news-reporter style, thoroughly removing himself from every bit of the story until only the court documents remain. The story of Chucky Taylor is crazy enough to stand on its own, but Dwyer himself has more tales to tell.