The Brooklyn Cocktail is a second-string, but by no means second-rate, pre-Prohibition classic and was largely forgotten until the recent cocktail renaissance. Now it is frequently found on drinks lists worldwide, both in its original form—first published in 1908 in Jack’s Manual by Jacob A. Grohusko—and in a host of other creative variations.

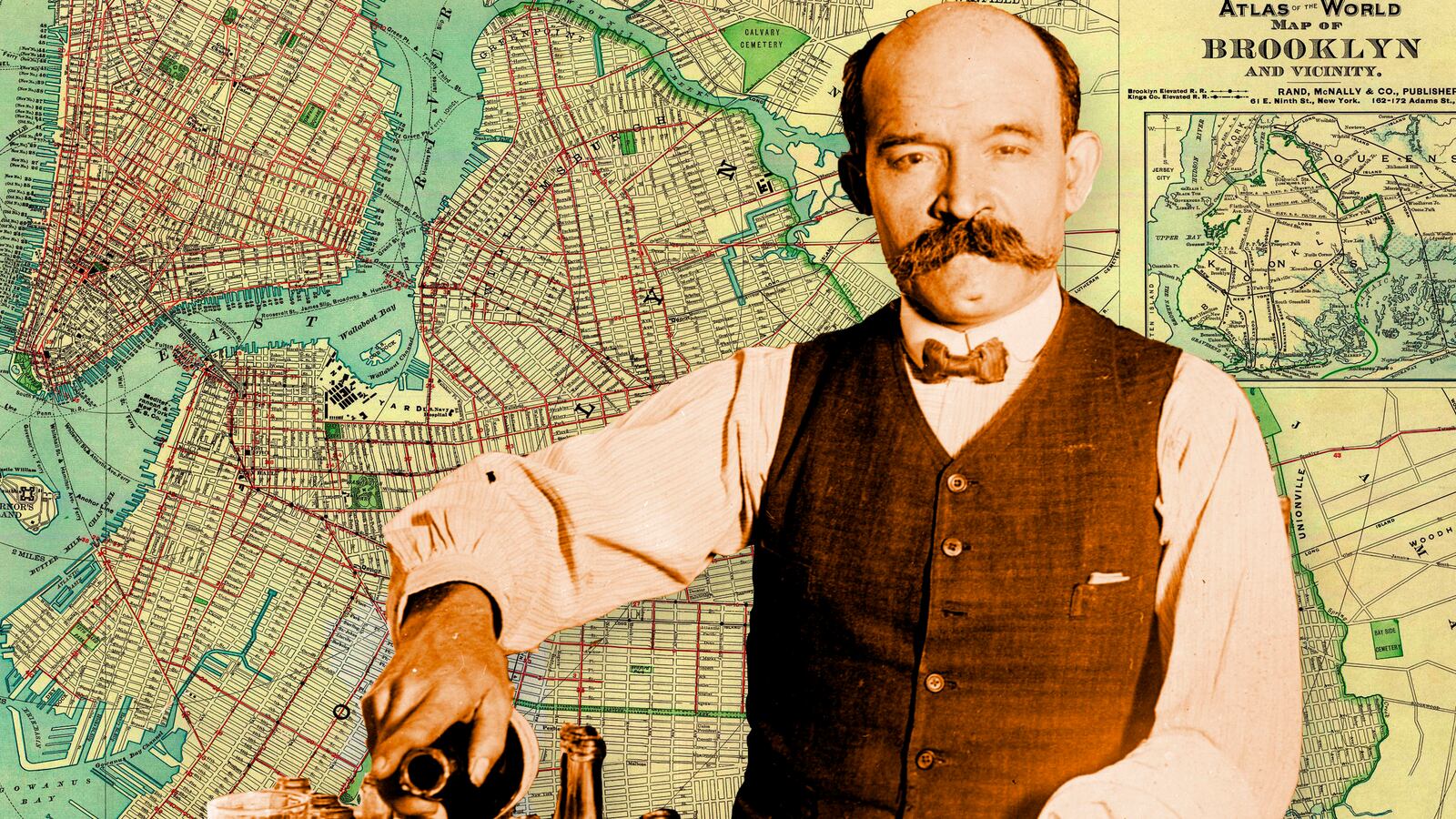

THE AUTHOR & THE DRINK

Jacob A. “Jack” Grohusko (1876-1943) was born in England to a Russian Jewish family and brought to New York as an infant. He worked in hotel bars in New York until around 1900, when he found a long-term gig at Baracca’s restaurant, on Stone Street in Lower Manhattan. Under his direction, Baracca’s bar was a popular one. In 1908, Grohusko published the first edition of his Jack’s Manual (there would be four more, from 1910 to 1933). In 1910, he opened his own place, also on Stone Street (the space is now occupied by Ulysses, one of New York’s best Irish bars).

We don’t know if Grohusko’s Brooklyn Cocktail, one of many drinks over the years to bear that name, was his own creation. He lived in Hoboken, New Jersey, not Brooklyn. Victor Baracca, however, the proprietor of the restaurant, lived in Brooklyn, so it’s at possible that he asked Grohusko to come up with something to match the venerable Manhattan and the newly-popular Bronx.

Grohusko’s version of the Brooklyn, with some tweaking, would outlast all the other similarly-named cocktails, largely though its inclusion in the canonical Savoy Cocktail Book of 1930.

THE ORIGINAL RECIPE

Brooklyn Cocktail

1 dash Amer. Picon bitters1 dash Maraschino50% rye whiskey50% Ballor Vermouth

Fill glass with ice.Stir and strain. Serve.

NOTES ON INGREDIENTS

Amer Picon, a French aperitif bitter, is not available in the U.S., and even if it were, it has been reformulated and lowered drastically in proof from what it was in 1908. Fortunately, in the small quantities called for here it is easy to substitute. The leading, but not dominant, note in Amer Picon is bitter orange, so any Italian amaro heavy on that, such as CioCiaro, will work well. (You can even, if necessary, use a less-orangey, but more available, amaro such as Montenegro, with a dash of orange bitters to boost the orange quotient.) Even better, I find, is the French Bigallet China-China Amer, a French digestif with a strong orange note. I generally use half a teaspoon, and the same amount for the maraschino liqueur.

For the rye whiskey, something bonded is in order. Rittenhouse is my go-to, but Wild Turkey Rye also works well. You don’t want anything less than 90-proof, since it has to stand up to a pretty strong cargo of vermouth. Grohusko would have used an ounce, but I prefer an ounce and a half.

As for that vermouth. Ballor, Grohusko’s preferred brand (its importer was around the corner from Baracca’s), was a classic Italian vermouth di Torino, dark and sweet. I like the Cocchi Vermouth di Torino here, but Martini & Rossi will also work fine if that’s what you’ve got. I would not use Carpano Antica, since its vanilla note tends to drive out all else before it.

Note that when Grohusko’s recipe was reprinted in Jacques Straub’s 1914 vest-pocket bartender’s compendium, Drinks, Straub inexplicably changed the Italian vermouth to a dry French vermouth (perhaps he didn’t know where Ballor was from). That’s the version taken up by the Savoy book, and it is, to my palate, distinctly inferior: thin and awkward. This is, however, the version most often encountered.

NOTES ON EXECUTION

Like the man says. Stir well with plenty of cracked ice and strain it into a chilled cocktail glass or coupe. I like a lemon twist with this.

The Annotated Cocktail presents a recipe for a classic drink exactly as it appeared for the first time in print and walks you through how to make it today so that it will be both historically accurate and delicious.