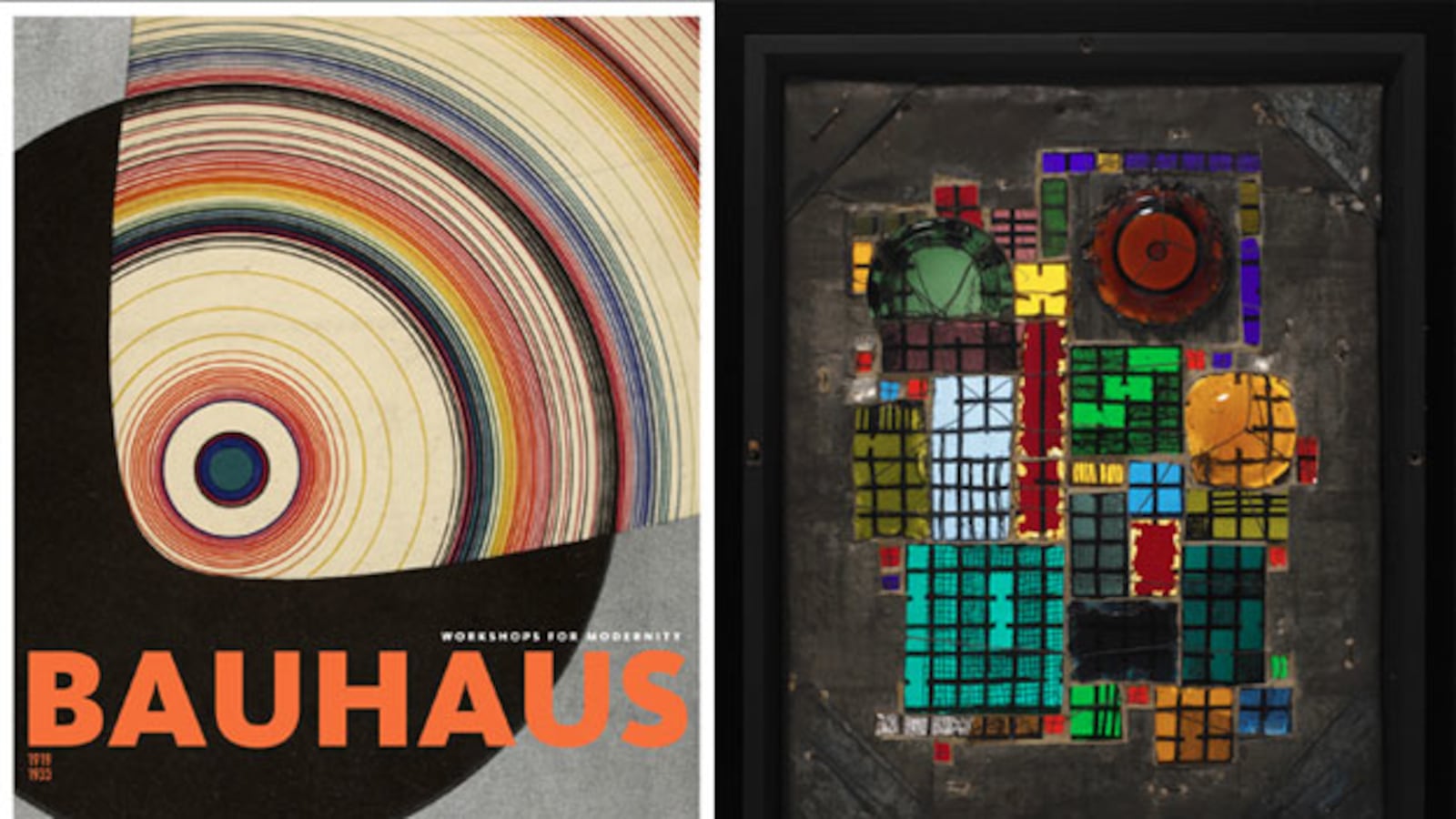

The game-changing art and architecture school, which founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius and shuttered by the Nazis in 1933, has had quite the comeback year—thanks, in large part, to a mega survey up at MoMA through January 25. The show’s companion book—which delves into the movement’s boxy post-industrial aesthetic as well as its revolutionary approach to arts education—is one of three excellent Bauhaus titles to hit the market this year. The other two: Nicholas Fox Weber’s The Bauhaus Group: Six Masters of Modernism (Knopf, $40) , and Ulrike Muller’s Bauhaus Women: Art, Handicraft, Design (Flammarion, $39.95) .

The first major survey of its kind, this book showcases paintings, sculptures, photographs, drawings, and installations created by a highly diverse group of artists working in and coming out of Africa. Some of them are familiar (Marlene Dumas, William Kentridge, Yinka Shonibare, Ghada Amer, Chris Ofili), but many are unknown (and that’s a good thing), but nearly all have found their own ways to confront the continent’s past, present, and future. Here’s hoping someone’s curatorial team (MoMA? Tate?) takes a cue…

The ultimate resource for critics, curators, collectors and industrious art nerds, this tome celebrates more than 500 of the best up-and-comers under the age of 33 from around the world. It’s from these 500 names that New Museum curators Massimiliano Gioni, Laura Hoptman, and Lauren Cornell selected the 200 or so artists shown in their first ever, pulse-taking triennial, Younger Than Jesus, on view at the museum earlier this year. To their credit, some of the names have already stuck (Ryan Trecartin, Cyprien Gaillard, Keren Cytter, and Tauba Auerbach among them).

It’s been a rocky year for James Rosenquist, the painter who changed Pop with his candy-colored renditions of fighter jets and 1960s-era auto parts. In April, his North Dakota home and studio burned to the ground (taking with it a hefty share of the artist’s archives and work). But in October, Rosenquist’s exuberant memoir,

Painting Below Zero: Notes on a Life in Art, was published, becoming one of the buzziest artist confessionals of the 21st century. Rosenquist, it seems, is at his best when dishing on his midcentury colleagues:

“Eventually I got to know de Kooning well. Once I went to see him out in East Hampton, and we had a few drinks. After a while he said, ‘Who the hell asked you to come here? Get out, you son of a bitch!’”

While not technically categorized as art photography, this ultimate archive compiles some of the best, most artful photographs ever taken by National Geographic’s all too anonymous correspondents. Composing this beast of a book was no easy task—editors had nearly 12 million photographs to choose from, spanning seven continents, all walks of life, and more than 100 years. Among their selections: late-19th-century daredevils scaling mountains and exploring the Arctic; Hawaiians witnessing a 1920 volcanic eruption; crowds wowed by one of Charles Lindbergh’s first flights; Saharan lion kings; Martian landscapes; and penguins, penguins, penguins.

This book dedicated to the late great Surrealist painter introduces some of Magritte's early commercial work and experiments with abstraction. There’s also a strong section dedicated to his post-World War II paintings in which the artist’s classic imagery (round supple apples, bowler-hatted men) reemerges on canvas but darkly cast in stone.

A massively definitive (2,500 pages, 4,300 illustrations…) and bank-breaking survey of Van Gogh’s tortured inner-workings contains every known letter written by or to the man himself. Sketches and paintings mentioned in the letters are reproduced as sidebars, as are various scholarly interpretations. But the real heart of the book is in the artist’s nuanced and extremely poignant writing—something that extends even to his signoff: “More soon, handshake. Ever yours, Vincent.”

Get in the mood for Nine with the 50th anniversary rerelease of William Klein’s stunning two-volume Rome. The photographer and documentary filmmaker shot most of the book’s black-and-white images when production was delayed on Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (on which he was serving as a staff photographer). Klein’s gritty and nuanced observations of Roman people and places were shaped, in part, by his excellent tour guide: Fellini himself.

Étant donnés, Marcel Duchamp’s R-rated piece de résistance, turned 40 this year, and it seems the art world is finally starting to figure out what the hell he was going for. The 448-page companion to the eye-opening show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art—where Étant donnés is permanently installed—and Book of Instructions, by Marcel Duchamp (Yale University Press, $40) offer unprecedented insight into the artist’s painstaking process, unmatched influence on contemporary art, and, via a never-before-released trove of letters, the passion and heartbreaks that inspired his most baffling work.

An American Leonardo centers around the “is it or isn’t it true” tale of a World War I vet who claimed to have discovered a previously unattributed painting by Leonardo da Vinci. John Brewer, a professor at the California Institute of Technology, seeks to solve this century-old controversy once and for all, but the book becomes less about the so-called Leonardo and more about the art world itself as stalwart appraisers, conservationists, and historians navigate a new era in authentication—one that is based on scientific and forensic testing. It all feels particularly relevant given a collector’s recent (and largely supported) claim that a $19,000 drawing he bought in 2007 is, in fact, a $150 million Leonardo. The proof? A fingerprint

Surrealism’s way-bigger-than-you’d-expect female contingency finally gets some overdue attention. Allmer builds a new timeline of the 20th-century artistic movement—one that starts with Eileen Agar’s mid-1930s photocollages and sculptures and ends with Francesca Woodman’s eerie black-and-white photographs from the 1970s.

During World War II, curators, archivists, artists, and art historians from some 13 countries joined forces as The Monuments Men. Their goal: Prevent and correct the holy mess Hitler made of Europe’s cultural heritage. Thanks to Edsel’s book, the Monuments Men (and women!), who recovered and hid looted artworks throughout the war while secretly seeking out tens of thousands of others, finally get their due. We smell a movie…

Leibovitz’s photographic memoir, finally out in paperback, demonstrates the sort of range we tend to forget she has. Sure, the book is chock full of the carefully staged celebrity photoshoots Leibovtiz is renowned for, but more compelling are the personal photographs included: Susan Sontag sprawled out on the couch in the couple’s Long Island summer home; Leibovitz herself, naked and pregnant; nieces and nephews frolicking on the beach. The book offers an unprecedented opportunity to reflect on Leibovitz’s entire body of work.

Shortly after the onset of World War I, the eminent Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, who specialized in schizophrenia, started to experience some symptoms of his own—visions, ghosts, waking dreams. Evoking a tool that was embraced by Surrealist artists at around the same time, Jung began to sketch his hyperactive and sometimes disturbing inner landscape. The Red Book, sort of a modern-day illuminated manuscript, grew from these drawings. And though few ever saw it in Jung’s lifetime, The Red Book laid out what would be his major contributions to the field of psychology (mainly, the concept of a collective unconscious). Jung’s 95-year-old tome has finally been published (as a facsimile and in translation) and his drawings (bright abstracted elements of nature, quasi religious imagery drawn from both Eastern and Western faiths) are on public view for the first time at New York’s Rubin Museum of Art (through February 15).

What happens when two arty hipsters go their separate ways? Lots of stuff—postcards, quirky photographs, art books, vintage duds… New York Times op-ed art director Leanne Shapton tells the fictional tale of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris’ flirtation, romance, and breakup through an auction catalogue documenting their shared and sentimental goods (to be sold at the fictional Strachan & Quinn Auctioneers). Shapton’s experiment in storytelling is touchingly effective—and certainly hasn’t gone without notice. Brad Pitt is said to have snapped up the film rights mere days after the book’s release. Word is he’ll be starring as Harold with Natalie Portman as his Lenore.

Without the cooperation of the Metropolitan Museum (“The only kind of books we find even vaguely palatable are those we control,” director emeritus Philippe de Montebello told the author in 2006), Gross has pieced together a compelling tale of the money, greed, egotism, and less than kosher acquisitions that have made the Met the megainstitution that it is today. It’s high culture meets lowlife behavior. And Gross has certainly dug up the goods—from Met-sanctioned tomb raiding in Cyprus to the classless antics of power-hungry trustees.

Investigative journalists Salisbury and Sujo have garnered praise for their account of the cinematic and very true tale of a British con man (John Drewe) and his unwitting accomplice (failed artist John Myatt). Starting in the mid-1980s, Drewe introduced more than 200 of Myatt’s paintings to the art market, some at six-figure prices. The only problem: He did so under other artists’ names (Alberto Giacometti, Georges Braque, et al.). Myatt’s fakes were quite good, but the real work of art here is the complex (and, of course, fictional) provenance Drewe would imbue upon each of Myatt’s “masterpieces,” complete with the falsified documents to back it up. The whistleblower ultimately came in the form of Mary Lisa Palmer, director of the Giacometti Association, and in 1998 both Johns were tried for their crimes. But, as Salisbury and Sujo note, the damage was done: Many of these works are still floating around public and private collections today.

Honor the master photographer’s recent passing with a look at some of his lesser-known work. In

Small Trades, a new book and exhibition (on view at the Getty Center in Los Angeles through January 10), Penn’s Vogue-ready subjects give way to ordinary people—window cleaners, maids, astronauts, constables, each clutching the tools of his or her trade. It’s a moving body of work and a reminder of Penn’s remarkable eye.

Irving Penn (American, born 1917)

Pompier, Paris,

Negative: 1950; Print: 1951

© 1951, restored 1996 Les Editions Condé Nast S.A.

This book is perhaps not the best gift for, say, Rudy Giuliani, who publicly crusaded against the artist’s The Holy Virgin Mary at the Brooklyn Museum in 1999. But this stunning and first-ever compilation of the Nigerian artist’s artistic oeuvre would likely suit just about everyone else. Friends (and no slacks themselves) Peter Doig, Kara Walker, and David Adjaye contribute poems and essays on Ofili’s singular aesthetic and Afro-centric imagery. Don’t miss an excellent section in the back of the book collecting the artist’s visual sources, which range from William Blake to Captain Sky among them.

Courtesy Chris Ofili/Afroco and David Zwirner, New York

In this slim volume, Danto, Columbia University professor emeritus and go-to guy for most things Warhol, sums up the Pop master’s evolution as both artist and persona. The book is not a traditional biography but rather, Danto writes, “a study of what makes Warhol so fascinating as an artist from a philosophical perspective.” It is, in essence, everything you need to dive deeper into Brillo boxes and Empire. Plus, the book already got a very public endorsement from The Daily Beast’s own Meghan McCain.