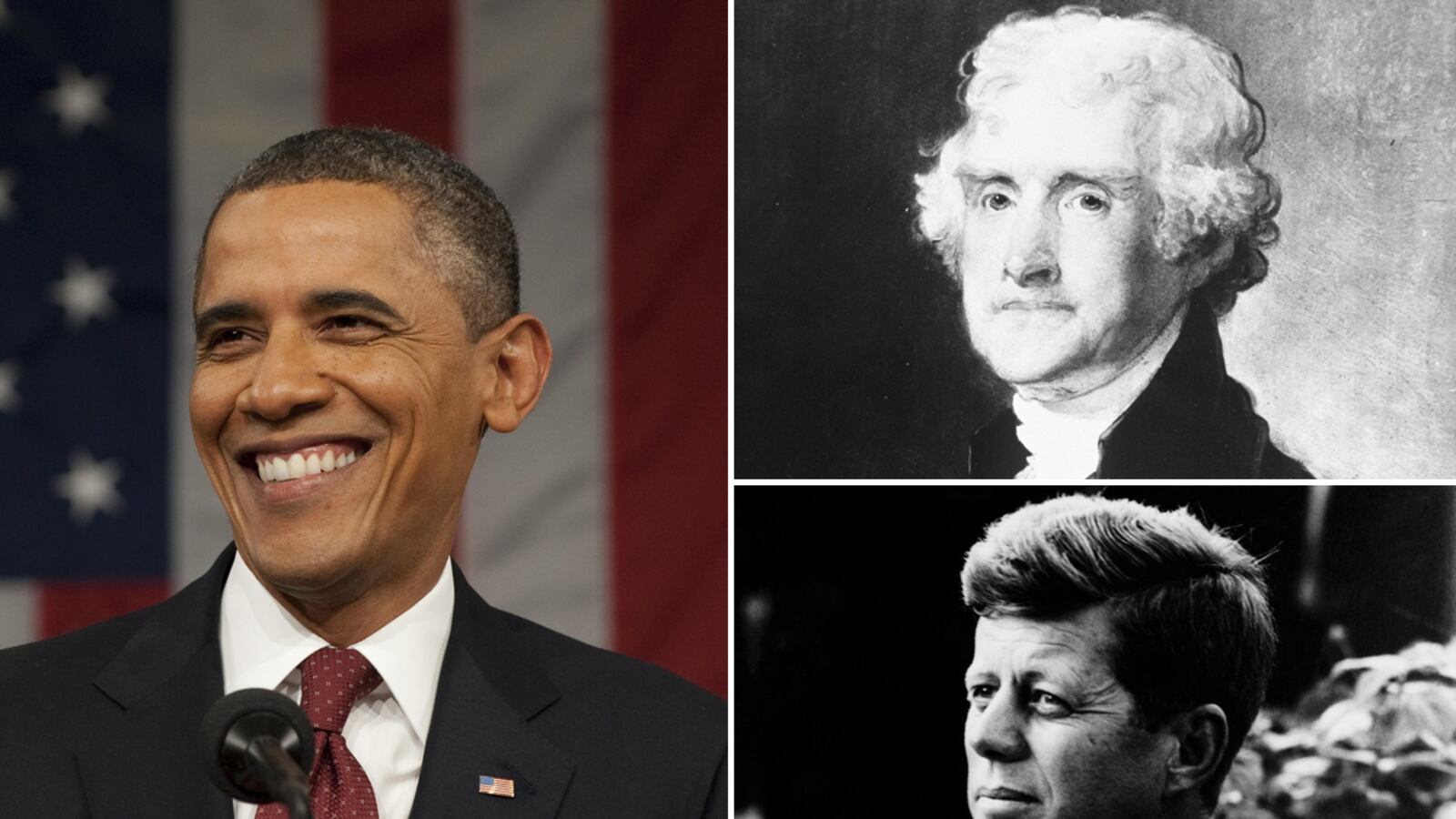

1. The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Adrienne Koch and William Peden

A treasure for lovers of American history as well as aficionados of Augustan prose, this is a superb combination of both personal writings (biographical sketches and more than 200 letters) as well as public papers including his two inaugural addresses and both the original and revised versions of the Declaration of Independence. The best one-volume Jefferson available.

2. Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 1832–1858, edited and annotated by Don E. Fehrenbacher

From the man Fred Kaplan called “the [Mark] Twain of our politics,” this is the first of two collections of Lincoln’s writings. The second is more reflective of Lincoln the statesman, while this one better reveals Lincoln the man with its hundreds of pages of letters to friends, colleagues, and to his wife, as well as the early speeches that made him a national figure (such as “House Divided,” delivered in Springfield, Illinois, in June 1858) and “Fragment on the Struggle Against Slavery,” written in July 1858. Also, if you want to see exactly how far the level of presidential campaign rhetoric has fallen over 15 decades, there is the entire text of the Lincoln-Douglas debates.

3. Ulysses S. Grant: Personal Memoirs/Selected Letters 1839–1865

A poll of American presidential scholars could well rank Grant’s personal memoirs as the best book written by an American president. Mark Twain thought it to be the most remarkable work of its kind since Caesar’s Commentaries; Matthew Arnold found Grant’s prose “straightforward … possessing in general the high merit of saying clearly in the fewest possible words that had to be said.”

Grant wrote his memoirs in 1885 at the breathtaking pace of 25–50 pages a day while in excruciating pain from throat cancer. (He died shortly after they were finished.) His work was published by his close friend Mark Twain. Candid, honest, and surprisingly self-effacing, Personal Memoirs is without parallel in American literature.

4. American Ideals and Other Essays, Social and Political, by Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt, according to Stephen Ambrose, “stands alone, unchallenged by any other twentieth century president, as a writer and scholar.” Teddy was prolific, too: 42 published books, many of which can still be found. Probably the most popular of his works are Hunting Trips of a Ranch Man (1893) and The Wilderness Hunter (1893), both of which are included in one volume from Modern Library. But TR was light years from the serial killer of game animals that some, in recent years, have called him. Ambrose says, “He came down hard on market hunters or anyone who killed for sport.”

Roosevelt the political thinker has too long been ignored, and his collection of essays, written from 1894 to 1897 and published in 1900 while he was governor of New York, is worth a revival. In American Ideals, TR presents a theory of government based on compromise and old-fashioned American pragmatism. It’s a working philosophy of politics much needed today.

5. Why England Slept by John F. Kennedy

While Profiles in Courage is regarded by many historians as the work of JFK’s speechwriter, Theodore Sorensen, Why England Slept is indisputably Kennedy’s work in its original form: it was his senior these at Harvard in 19540. Kennedy makes a strong position, no doubt influenced by his father, that appeasement toward Germany in the late 1930s was good policy as Britain and France weren’t sufficiently armed to hold the Nazis in check. The book suggests that Kennedy could have made a solid if contrarian historian if he hadn’t been groomed for politics.

(Why England Slept, is available in several reprinted editions. A first edition from 1940 goes for $30,000, but the 1961 hardcover editions in good condition are as low as $30 and Amazon even rents the latest 1982 edition.)

6. Six Crises by Richard M. Nixon

Nixon was no Teddy Roosevelt, but he could write. Nixon writes lucidly and with insight on the biggest crises of his political career: the 1948 testimony of Whittaker Chambers that State Department official Alger Hiss was a member of the Communist Party; the accusation that he took bribes from which he defended himself in this famous 1952 Checkers speech; his service as acting president following Dwight D. Eisenhower’s heart attack in 1955; a 1958 attack on the vice president and his wife in Venezuela by what Nixon called “pro-Communist mobs”; the famous “kitchen debate in 1959 between Nixon and USSR Premier Nikita Khrushchev (Nixon believed he won); and his hard-fought but losing campaign against JFK in 1960. Six Crises is exciting reading, if a tad self-serving.

The most valuable copy in the world would be the one somewhere in a Beijing library that Nixon autographed for Mao on his 1972 visit. Mao read the book before Nixon arrived.

7. Dreams From My Father, A Story of Race and Inheritance by Barack Obama

Writing of Obama’s Dreams From My Father and The Audacity of Hope, Christopher Buckley commented that both works were “first-rate, he is that rara avis, a politician who writes his own books.” Of the two, Dreams is the more personal and the most important for anyone seeking insight into the mind of our president.

There is nothing remotely like Dreams From My Father from the pen of any other American president. In fact, it could reasonably be called the first book ever by a president that examines the subject of race in America straight-up. Writing of the father he remembered meeting only once, Obama concludes that the many stories he heard about him “said less about the man himself than about the changes that had taken place and the people around him … The stories gave voice to a spirit that would grip the nation for that fleeting period between Kennedy’s election and the passage of the Voting Rights Act … a bright new world where differences of race or culture would instruct and amuse and perhaps even ennoble.”