Crime fiction spends a great deal of time sorting through the chaos to find some order, a sense of resolution for the often inexplicable madness of murder. Real crimes, however, don’t work that way. Evidence is misfiled, suspects evade arrest on technicalities, investigations stretch out for years before an end comes in sight—if at all. True crime is a messier affair, but in the hands of these writers, the true specter of violence and mayhem, science and psychology is elevated to literary art.

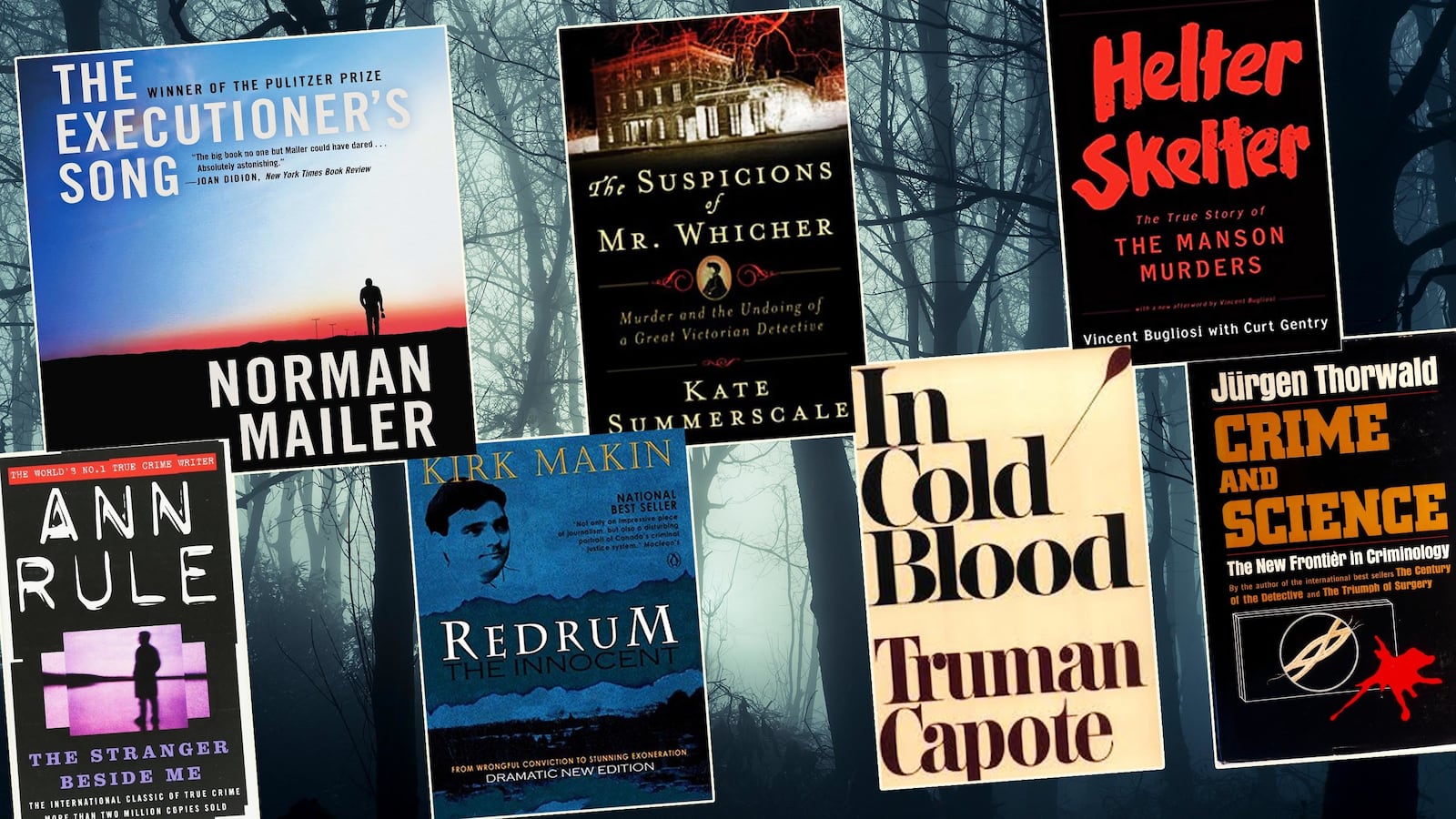

In Cold Blood By Truman Capote

In many ways, this is the ur-true crime text, defining the upper limit of what this often sneered-upon genre can do: use the story of one grisly act as a jumping-off point for larger considerations of the human condition. The bare bones of how Perry Smith and Dick Hickock tortured and killed the Clutter family are easily available via Wikipedia, but settling for the facts is like choosing McDonald’s over Peter Luger’s for your burger. Capote’s account of the crime’s impact on the small town of Holcomb, Kansas illuminates the banality of evil, and reminds us how thin is the line that separates horror from normality.

Crime and Science By Jürgen Thorwald

I received this book as a birthday gift from my college roommate during my freshman year, and I think it played a huge role in why I pursued a master's degree in forensic science. Thorwald writes with exceptional clarity about cases obscure and famous that were solved through forensic techniques like blood typing and elemental analysis of gunshot residue. They may now seem quaint in the age of DNA and CSI-style glamorization, but current criminalists owe a lot to their chemically minded pioneers. Both this book and its earlier companion volume, The Century of Detective—which lost the Edgar Award for Best Fact Crime to In Cold Blood—ought to be rescued from out-of-print neglect.

Helter Skelter By Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry

The passage of time erased much of the hullabaloo and misinformation about the many horrible crimes of Charles Manson and his followers, so that we’re left with echoes of tepid outrage and discomfort at the brain cancer death of Susan Atkins, another parole bid denied by Leslie Van Houten, or a recent photo of the septuagenarian leader with the faded swastika tattoo on his forehead. But Bugliosi and Gentry’s epic account of the murders and prosecution is an excellent refresher. They take us back to the agonizing weeks when nobody knew who murdered beautiful, pregnant Sharon Tate (Roman Polanski’s wife) and her companions, and examine Manson’s corrosive, cult-like charisma, which spurred so many aimless youths to kill in his name.

The Executioner’s Song By Norman Mailer, with Lawrence Schiller

Technically, this is “a true life novel,” which allowed Mailer—who collaborated with long-time friend, writer, and literary executor Schiller on the research—to hedge his bets with regards to sticking entirely to facts and figures. But there is no repudiating the enormous scope, sweep, and power of The Executioner’s Song, which reveals every nook and cranny relating to the troubled life and firing-squad death of Utah multiple murderer Gary Gilmore—the first person to be executed following the 1976 re-institution of the death penalty. Mailer gives voice to Gilmore's victims (dead and living), never shirks on details, and largely stays out of the way of the narrative, creating a multifaceted, disquieting portrait of a man who murdered, instead of a monstrous caricature.

The Stranger Beside Me By Ann Rule

It may not be the best book about serial killer Ted Bundy, or even Ann Rule’s best book. But 30 years later, Rule’s story of how she spent years volunteering with Bundy at a crisis hotline still prompts chills to run up and down my spine, because we can and should ask: Would you be able to spot a sadistic murderer if he presented himself as charming and friendly? Obviously, we want that answer to be a resounding yes. The truth is much more complicated, and Bundy’s double life allowed him to murder scores of young women until his final capture and eventual execution.

Redrum the Innocent By Kirk Makin

This 800-page volume was a lightning rod for discussion when it was published in my native Canada, for it deals, exhaustively and comprehensively, with one of the most troubling criminal chapters in that country’s history. Nine-year-old Christine Jessop was raped and strangled to death in 1984, and law enforcement convinced themselves that neighbor Guy Paul Morin killed her. He was acquitted, then convicted (Canada doesn’t have double jeopardy) and then DNA testing freed him for good. But Jessop’s killer remains at large, and we’re left with the many mistakes made by Ontario’s police force in what they thought was justice, but was the exact opposite.

The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher By Kate Summerscale

Summerscale’s deserved international bestseller takes a cue from the “sensational” novels of Wilkie Collins in her elegantly written telling of the story of the first modern detective, Jonathan Whicher, and his ultimately doomed investigation of the 1860 murder of 3-year-old Saville Kent. The crime had a constrained, country house locale, a limited number of suspects, and a dogged detective whose very profession was still new and distrusted, all elements of a wonderful and suspenseful traditional mystery. The suspense builds to a climax as Whicher names the killer and then—even though he’s later proven correct by a confession—sees his reputation ruined.

Sarah Weinman contributes to the Los Angeles Times, the Baltimore Sun, the New York Post and many other print and online publications, and blogs about books and the publishing industry at Confessions of an Idiosyncratic Mind.