About half an hour before recess, the 25 students of Dana Campo’s fifth and sixth grade combo class move their chairs—most of them grumbling—into an uneven circle at the front of the room. There were 13 girls and 12 boys, and by Dana Campo’s estimate, a good portion of them are here in the country illegally.

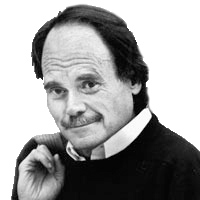

This was back before Christmas, and I (the former teacher known as Mr. Nale) had dropped in one morning to watch her teach. She and I were partners once, teaching a class like this—but larger—together for three years. She is a genius with kids and I wanted to see how she was doing.

The kids are grumbling partly because they are waiting for recess and partly because the circle means it is time for the daily class meeting. The class meeting is a new idea in teaching, meant to create community by establishing an equal dialogue. Which is to say that for a little while they lose their status. Smart kids and dumb kids, tough kids and nerds (sometimes referred to in this class as macheteros), the glamorous girls and the ones not allowed to wear lipstick—for a little while each day everyone’s voice carries the same weight. It’s part of the rules.

To talk during Ms. Campo's meetings, a kid raises a hand and is given a ball – a foam replica of Earth – that allows her or him to speak. Only one student is allowed to talk at a time, no one interrupts, and while he or she is talking, everyone else in the circle is supposed to pay attention. This means more than no fistfights in the aisle; it means looking at the speaker. Listening. One other rule: no names. Complaints are made generally, not aimed at particular students, although most everyone in the room, including Ms. Campo, knows who is who.

The issue of the day is bullying. There is some small amount of sneering around the circle at the announcement of the topic. Three boys in particular—Joshua, Angel, and Jesus—I can tell from long experience are probably bullies themselves. And Angel is probably the leader.

Ms. Campo asks her class the question: how does it feel to be bullied? It is quiet for a moment. Kids look at each other, look away, then a sixth grader raises his hand. “Embarrassed,” he says. “It makes you feel bad, and embarrassed. Like, they ruin your whole day.”

Heads nod all around the circle, and the three boys—Angel, Jesus, and Joshua—grin in a predatory way at the first kid for acting like a punk. My friend Dana, who has been at this 13 years, stares them down. I have known Ms. Campo a long time and try to remember if we have ever talked about why kids named Angel and Jesus are always the worst troublemakers in the class. Not always always, of course, but a wild skewing of probability.

“What about outside of school?” Ms. Campo asks her circle. “Has anybody seen bullying outside of school?”

A kid named Fernando says he sees it on the highway when his mom is driving him to school. A fifth grader says she has an uncle who gets drunk and bullies everybody. She hates it when he starts to drink, and with time I think she will probably grow to hating the uncle himself.

Angel, Jesus, and Joshua continue to smirk, but now one kid after another is raising his and her hand, and the tormenters of Ms. Campo’s class begin to notice the change in mood, the kids feeling braver for having confessed to being afraid. Hearing that they aren’t in it alone.

The tiniest kid in Ms. Campo’s class is a beautiful little girl named Bee-Bee (for Veronica), who could easily be three years younger than the others. She sits in the chair beside Ms. Campo, quiet and shy, listening. When Bee-Bee first came into Dana’s class, she spoke so rarely, so softly that my old friend wondered if the girl had a speech impairment. She raises her hand now—surprising in itself—and says, “On the news.”

And almost like a signal, more kids begin jump into it now, and when Ms. Campo asks how it makes them feel to see and hear adults shouting at each other on television—bullying each other—more hands go up all at once, and the damage that Donald Trump did to get himself elected President begins to show up. A whole room full of kids—all but one Hispanic—afraid of deportation.

A sixth grader says her grandparents warn her not to attract attention. A fifth grader says Donald Trump wants to deport everybody, and then Bee-Bee, the smallest child in the class, raises her hand again. Her voice is shaky now, soft and timid. She says, “My mom was deported,” and the room goes quiet again.

“She dropped me off at school and didn’t come to pick me up. It got late and then my aunt came and got me, and told me they’d taken her away.” She holds back as long as she can and then begins to sob. Dana puts an arm around the child, then both arms, and holds onto her while she tries to stop crying. From what Dana knows, Veronica's mother had a visitor’s visa that expired and she hadn’t had the money to apply for a residency card. Then some unknown patriot—keep in mind this could be some old family grudge or a neighbor who didn’t like her looks, anyone at all, but it is probably something personal—turned her in.

Another girl begins to cry too. Then more. Me, I’m watching Angel. Seeing how public opinion is going, he puts his hands in his face and pretends to cry too. The kid shows every sign of a career in politics. Meanwhile, the talking ball goes back and forth around the circle, Ms. Campo continues to comfort Veronica, and now everyone has something to say about bullies. Suddenly it’s a real conversation, kids open up and show real opinions.

Angel looks up from time to time to see if Ms. Campo has noticed he is crying too, and his two friends—who’d thought Angel was making a joke of it at first—Joshua and Jesus put their faces in their hands and pretend to cry too. And maybe this is progress, and maybe it isn’t. I promise you that Angel, Jesus, and Joshua have not just changed who they are, but there are 22 other kids in the room, and maybe they have glimpsed something about strength in numbers, maybe they have learned something about standing up for themselves from the tiniest, shyest kid in the class.