Seven years ago, a pair of scientists scouring high-resolution images of space caught fleeting glimpses of a bright round object peeking from a vast cloud of icy objects more than 2 billion miles from Earth.

As if that whole scene wasn’t exciting enough, the object appeared to be a huge comet. Thought to be between 60 and 100 miles wide, it was the biggest comet a human being had ever witnessed. And it seemed to be heading toward us, very loosely speaking.

Last month the discoverers of the giant object—University of Pennsylvania astronomers Gary Bernstein and Pedro Bernardinelli—combined their earlier data with fresh sightings of the distant object this summer and confirmed their suspicions.

Yep, it’s a megacomet. “The nearly spherical cow of comets,” they quipped in the title of their paper, which they submitted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on Sept. 23. And the pair have also learned the comet’s trajectory has it swinging between Uranus and Saturn in 2031.

Besides setting up an astronomically great joke, the Bernardinelli-Bernstein comet is a very rare and unique prize for any scientist trying to piece together the history of the solar system. “In essence, it’s a time machine,” Amy Mainzer, an astronomer and comet expert at the University of Arizona, told The Daily Beast. The comet’s journey is the opportunity of a lifetime for scientists anxious to learn about the conditions and building blocks of the solar system that one day led to Earth and all its life.

A comet is a return visitor from the collisions of space rocks that created Earth and almost everything else in our corner of space a very long time ago. “The story told by the comet would tell us of what existed in the solar system billions of years ago, and we can use that to understand the things we see today elsewhere in the solar system,” Bernardinelli told The Daily Beast.

But every comet we’ve been lucky enough to closely study so far has changed a lot over time—either because they were too small to avoid fragmentation, or because they passed so close to the sun that they were in the star’s intense heat, altering their chemistry. That means the story it tells about the early solar system has been, to say the least, edited by outside forces.

Bernardinelli-Bernstein has escaped both fates. “It’s pristine,” Bernardinelli said. “Not a lot has happened to this object since its formation in the early days of the solar system, and so we can think of it as a window into the past.”

Because it’s so much bigger than other known comets—the famous Hale-Bopp comet, which itself is on the larger side, measures just 37 miles across—Bernardinelli-Bernstein possesses enough gravity to hold itself together as it lazily loops through space. It’s harder to break apart..

The comet’s extreme distance from the sun also helped preserve it. “It spends most of its time in the deep freeze of the outer solar system,” Mainzer explained. Models of the megacomet’s orbit indicate it last entered our part of the solar system around 5 million years ago and got no closer than Uranus. From that distance, the sun’s heat hardly touched it.

Mainzer says that as a result, the comet she affectionately calls “BB” probably resembles the original chemical state of the nebula of gas and dust that formed our solar system about 4.5 billion years ago.

The trajectory of Bernardinelli-Bernstein as it makes its close approach in 2031. The comet will zip through between the orbits of Uranus of Saturn.

NASAIts close approach in 2031 will be a monumental time to study the comet’s chemistry and reveal what our neck of the woods was like before there were planets zipping around. “One of the best things about this comet is that we’ve got a while until it makes its closest approach to the sun, so we’ve got years to study how it brightens up as its surface gets exposed to the sun’s warmth,” Mainzer said.

That warm-up act is critical, since it causes a comet to shed huge amounts of dust particles and produce that distinctive comet tail. “By watching the show as the comet creeps closer, we’ll be able to tell more about which chemicals act like the propellant in the spray can, so to speak, pushing rocky particles and dust off its surface,” Mainzer explained.

What doesn’t come off the megacomet’s surface is as important as what does. Are the reactions carbon dioxide-based or nitrogen-based? Current observations suggest Bernardinelli-Bernstein contains a lot of the former but comparatively little of the latter, Bernstein said.

That mix matters. Nitrogen is really common on Pluto, the tiny planet (or “planetoid,” if you side with the critics) that’s farther from the sun than any other main planet. It’s possible Pluto still has its nitrogen because it’s too far from the Sun for that chemical to evaporate.

If Bernardinelli-Bernstein really is low on nitrogen, “maybe that means that this comet was living closer to the sun than Pluto when it was young,” Bernstein said. That could make Bernardinelli-Bernstein a nearer relative to our own planet than Pluto is, chemically speaking.

Mainzer emphasized that the the comet's older, colder inner layers that don’t heat up easily could be even more interesting, since they may help reveal what exactly comprised the gas and dust cloud from which our solar system was born.

We can, in other words, fill in some of the vast gaps in the chemical blueprints of our own evolution—and inch closer to understanding where life, and the planets that support it, come from.

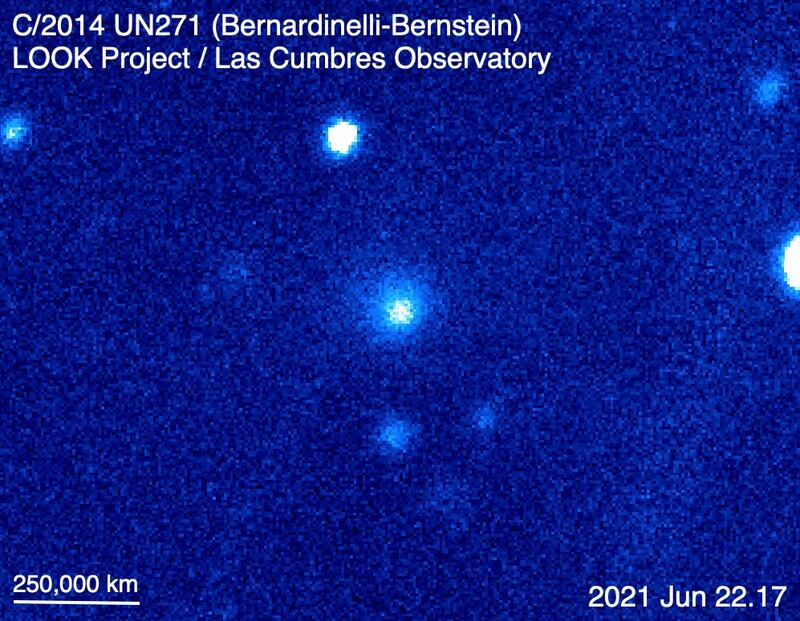

Bernardinelli-Bernstein as seen by the Las Cumbres Observatory 1-meter telescope at Sutherland, South Africa.

LOOK/LCOFor all its promise, there’s also a downside to Bernardinelli-Bernstein’s recent discovery. A decade or more might seem like a long time to study a single object in space. But considering how long it takes to conceptualize, fund, organize, and execute a new space mission, it’s actually not very long at all. The only tools we can count on for examining the megacomet are the ones we already have—or which are near completion.

“Big telescopes are our best bet now,” Bernardinelli said. Those include the same telescopes astronomers have already used to inspect Bernardinelli-Bernstein plus the optics at the Vera Rubin Observatory that’s scheduled to open in 2023. Bernstein said it’s possible NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope, which should launch later this year, might also spend some time pointed at the megacomet.

It’s highly unlikely NASA or some other space agency building a probe to intercept and collect samples from Bernardinelli-Bernstein (which is ironically what NASA is currently doing with the asteroids surrounding Jupiter).

But it’s not impossible, and Mainzer for one isn’t giving up hope that some space agency might see the value in retrieving an actual hunk of ice from Bernardinelli-Bernstein—and do what it takes to slap together a probe. “I think BB would be a great target for an up-close-and-personal visit,” she said.