It was four months into America’s muddled and chaotic coronavirus response, and lawmakers finally thought they had found the right man to track a half-trillion dollar pot of emergency COVID relief loans: former Gen. Joseph Dunford.

To that point, Speaker Nancy Pelosi and then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell—both required to sign off on a chairperson for the Congressional Oversight Commission—had not, in fact, agreed on a candidate. Few had seemingly wanted the job. One aide described the chairmanship to The Daily Beast as having “a lot of suck and not a lot of upside.”

Ultimately, Dunford didn’t want it either. The former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff told The Daily Beast that he initially accepted the offer last summer but later backed out when he learned he would have to relinquish his board positions at corporations, such as defense contractor Lockheed Martin, and various nonprofits—all of which could have received relief funds. He offered to serve as chair without compensation, but said that proposal didn’t work out.

“I would have done it, were I at a different stage in life, and were the requirements different,” said Dunford, who retired from a career in the military in late 2019. “I’m disappointed we couldn’t figure out how to waive those requirements, because I believe I could have acted in a good-faith, nonpartisan way.”

Once Dunford walked away, oversight advocates were once again in despair and back to square one. And the despair was well-founded: In the eight months since Dunford turned down the job, Pelosi and McConnell have never again been close to agreeing on a chair.

Now, nearly a year since the passage of the CARES Act—the initial $2.3 trillion COVID relief package—the oversight body hyped as the most visible steward of funds to safeguard the economy has largely been an afterthought. During the dire, uncertain early days of the pandemic, that four-person panel functioned on a limited basis—short-staffed and under-resourced—as it waited on the two leaders to agree on a chair. But the panel sputtered after Dunford bowed out and inertia of the 2020 election season took hold. By the end of the year, the pandemic lending program actually ended before the body meant to oversee it fully got off the ground.

“When the Trump administration announced they were going to shut down the lending facilities, that took all the wind out of the sails,” said the source familiar with the panel’s workings. “To the extent there was any wind in the sails, it was gone at that point.”

Sean Moulton, a senior policy analyst at a nonpartisan oversight watchdog—Project On Government Oversight—called the failure to name a chair embarrassing for Congress. “The lack of a chair,” Moulton said, “just really hobbled the congressional commission quite a bit.”

And the inability to agree on a chair may just be the very beginning of the failures of the commission.

The body was supposed to keep watch over an important, but relatively small slice of the enormous pile of cash that Congress approved last year to counter the pandemic, a total of $3.3 trillion as of December 2020. Other oversight mechanisms set up by the CARES Act, and later by House Democrats, have fared relatively better. But all of the accountability structures have struggled to grasp the immense scope of the federal response, which has directly touched hundreds of millions of American households and businesses.

A March 11 report from the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, a group of federal agency inspectors general, offers an understated but candid admission of the challenge: “It must be emphasized,” read the report, “that evaluating the impact of Coronavirus response funds is fundamentally a difficult assessment due to the magnitude of the crisis.”

As the pandemic now stretches into its second year—and President Joe Biden’s newly minted administration implements another massive COVID relief package—the impact of 2020’s oversight failure is hardly esoteric. For one, the existence of widespread fraud and waste in the pandemic response is simply accepted as fact by most observers. The cost to taxpayers could be astronomical; last year, Michael Horowitz, the chair of the PRAC, said that if just 1 percent of total funds spent were misused, the cost would exceed the annual budget of the entire Department of Justice.

Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA), a member of the House Oversight Committee who has been the House’s most vocal proponent of aggressive pandemic oversight, conceded lawmakers “really don’t have a great handle” on how high the losses might be.

Those failures simply corrode public trust that the programs they paid for are working, said Porter. And experts add that not adequately understanding those failures makes them more likely to happen again.

“Even successful parts of the rescue packages from last year are opaque and difficult to track by the government and by outsiders, making it difficult to understand whether taxpayer dollars were spent properly and against what standards,” said Austin Evers, executive director of the watchdog group American Oversight, which has independently tracked the pandemic response.

“If a new pandemic hits tomorrow, I’m not sure what lessons we could quickly glean from the last year to come up with a new CARES Act,” said Evers. “That to me should be our North Star right now.”

The fate of the COC as a metaphor for the federal government’s halting approach to COVID oversight is, for many observers, too neat to ignore. Despite its narrower purview, outside experts and Hill staffers had initially hoped an aggressive panel could signal that Washington was taking accountability for the sweeping pandemic relief effort seriously—not unlike the noisy, high-profile bank bailout watchdog panel led in 2009 by Elizabeth Warren.

“What I think a lot of people were hoping for was for it to strike a leadership role, use their programs as a mean to say, ‘this is what we’re demanding, these are problems we’re going to fix, this is the kind of transparency and accountability we expect in other programs,’” said POGO’s Moulton.

The hope on the panel, the source familiar with its workings said, was that “our jurisdiction is limited, but maybe we can get more bang for the buck.”

But problems were baked into the commission’s structure from the start. Congress created the commission through a bipartisan compromise in the CARES Act, requiring the buy-in of both parties in the House and Senate, and the signature of then-President Trump. “We didn’t have adequate oversight authority—no subpoena power—and that was hard to overcome,” said the source familiar with the commission.

Additionally, many Democrats felt the requirement that McConnell and Pelosi agree on a chair made the project fatally flawed from the get-go.

“Show me where Mitch McConnell and Nancy Pelosi agree,” said Porter. “That was a bad way to structure this commission right from the start.”

Porter said, at her most skeptical, she wondered “if they didn’t see that at the beginning, or one side didn’t see that—like, gee, if you require us to agree, nothing will go forward.” Pelosi and McConnell’s offices did not respond to requests for comment on the chairperson selection process.

Former Rep. Donna Shalala (D-FL), who was Pelosi’s appointment to the COC and continues to serve on the panel, acknowledged that their lack of subpoena power was a real challenge. But she said that Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, and other top financial officials, were cooperative.

“We weren't so political,” Shalala told The Daily Beast. “While we disagreed on some things, we tried to work things out. We weren't doing this in public hearings where everyone was trying to get a sound bite.”

Although the lack of a chair prevented the panel from hiring a full staff, it ended up producing monthly reports on how the Treasury Department used the $500 billion fund in the CARES Act to provide a lifeline to businesses, local governments, and companies deemed critical to national security.

Ultimately, only a small portion of those funds, roughly $60 billion, were actually lent. There may have ultimately been less need than anticipated for those emergency loans, which were modeled after those deployed in the 2008-2009 financial crisis. But critics contend that the requirements for securing a loan were too onerous, particularly for smaller businesses, and the Trump administration was far too cautious about issuing them.

The COC’s highest-profile finding came in July, when members raised concerns about a $750 million loan that Mnuchin granted to a trucking company, concluding that the company may likely default. Later, Mnuchin admitted the loan was “risky,” but he said the government did not take a loss.

Rep. Raja Krishamoorthi (D-IL), who serves on the House’s Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, said a more functional COC could have gotten answers and pushed for improvements to the lending program in real time. “I was very disappointed about the implementation of that particular loan program,” said Krishnamoorthi. “It’s disturbing that the government can’t get its act together to come to people's assistance even when it has access to funding to do so.”

The other oversight mechanisms set up by the CARES Act have been arguably more effective. The PRAC, for example, has embarked on a broad effort to grasp waste, fraud, mismanagement and abuse in the COVID response across government, while posting their findings and reams of data for public consumption in the process. A PRAC spokesperson said a key success of the body has been “fraud investigations and insights that have resulted in multiple reports to [the Small Business Administration] and Department of Labor on ways to prevent future fraud.”

The Select Subcommittee, meanwhile, has been a politically charged enterprise. House Republicans accused Pelosi of creating it to “legitimize partisan attacks” on the Trump administration. But Democrats have cheered the panel’s dozens of investigations and hearings. Norm Eisen, a Brookings Institution senior fellow who was President Obama’s point person for ethics and oversight, called it “the star” of the oversight bodies that have been at work in the last year.

But even when these oversight mechanisms work, there’s been little in the way of leadership to synthesize key findings and make recommendations to policymakers on how to improve the pandemic response.

“The coronavirus oversight today is very much a modern day example of the allegory of the blind man and the elephant: a lot of close study of small details, but it’s hard to step back and really understand what we’re seeing,” said Evers. “The oversight mechanisms put in place in 2020 very quickly revealed themselves to be balkanized and inadequate.”

Evers added that what was missing at the federal level was someone gathering information and drawing lessons.

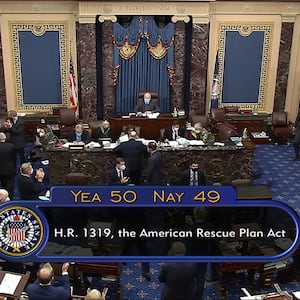

Oversight advocates are hoping that Biden will change that. In his $1.9 trillion relief bill, Biden and Democrats did not stand up any new oversight mechanisms for the massive extension of pandemic relief programs, but they did extend more funding for existing entities like the PRAC. Biden also named the veteran economic policy adviser Gene Sperling as his “czar” in overseeing the effective implementation of the bill, though the White House has offered little in the way of specifics about Sperling’s oversight purview.

“While respecting the independence of the PRAC and agency Inspectors General, we believe the American people are best served when we work cooperatively and proactively with oversight officials to minimize fraud and build integrity, trust, and effectiveness in these emergency efforts,” said a White House official in response to questions about their specific plans for relief oversight. “That was President Biden’s philosophy when he managed implementation of the American Recovery Act as vice president, and it will be his philosophy in coordinating implementation of the American Rescue Plan.”

Eisen said Sperling is someone “who understands the damage that the Biden administration will suffer if these funds go awry.” And he added that he looks forward to seeing Biden’s full oversight plan for the rescue package.

“I’m guardedly optimistic,” Eisen said. “But I and others will be watching closely to see what happens next, including who Biden and Gene Sperling put in charge of these issues as they take their next steps.”

In the interim, there might be a glimmer of hope for the beleaguered Congressional Oversight Commission. With Democrats now in control of the Senate, Pelosi and now-Majority Leader Chuck Schumer could jointly name a chair for the panel.

Shalala said she expects an announcement soon.

“Hopefully, this month,” she said.