The crazed woman who stabbed the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King in the chest with a letter opener in a Harlem department store in 1958 summoned such force that it pieced his sternum and the honed point stopped just a fraction of an inch from his aorta.

King was later said to have been within a sneeze or a jolt of extinction. Were it not for the pair of cops who gingerly carried him from Blumstein’s department store and the pair of surgeons who performed lifesaving surgery at Harlem Hospital there would have been no “I Have a Dream” speech and likely no national holiday honoring him.

As it happened, one of the cops was Black, the other white and the same was the case with the two surgeons. Each pair worked as true partners, proving that the color of their skin meant nothing and translating the content of their character into life-saving action. They demonstrated by doing what they did the way they did it that what mattered was their shared knowledge and skill and nerve.

Here was a vision right out of the very dream that was in dire danger of never being voiced as the tip of the letter opener sat so close to an artery pulsing with pressure that could instantly turn just a nick into a fatal tear.

The cops were Al Howard and Phil Romano. They had been in a radio car near the end of their tour at 3:30 pm on September 20 of that year when they received a report of a disturbance in Blumstein’s Department store. They arrived to see the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King sitting in a chair beside a stack of his new book, Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story that he had come to sign. An ivory handled letter opener protruded from his chest.

"We have to do something!" a panicked onlooker screamed.

The onlooker reached to pull out the letter opener. King almost certainly would have died right there and then if the cops had not stopped her. The cops rightly sensed the precariousness of the situation.

“Don’t sneeze,” Howard was heard to tell King. “Don’t even speak.”

Howard and Romano decided to leave King in the chair and carry him in it ever so gingerly down the stairs and out of the store. An ambulance took King to Harlem Hospital, which had been alerted and was notifying its top team of trauma surgeons, Dr. John W. V. Cordice, Jr. and Dr. Emil Naclerio.

Cordice was the son of a North Carolina doctor, but he had hoped to become an engineer and an aviator like Charles Lindbergh. Young Cordice was then advised that such a career path was not open to an African-American. He followed his father into medicine, which proved to be difficult enough given the prevailing racial attitudes of the time.

During World War II, Cordice got closer to his original dream when he became the physician for the newly formed all African-American fighter pilot unit, the Tuskegee Airmen. He afterwards learned French and spent a year in France, where he assisted in that country’s first open-heart surgery.

Back home, he became the chief of thoracic and vascular surgery at Harlem Hospital. He also had an office in Brooklyn and the phone there was ringing when he stopped by on what would prove to be such a fateful day.

Cordice headed straight to Harlem Hospital. The resident on the phone had only told him that “a person of great interest” had been brought into the emergency room. Cordice learned on his arrival that the person was King.

“I had heard of him, of course, but I had not known him personally at all,” Cordice later told radio station WNYC. “He had not achieved the level of fame he later achieved. But he was on his way.”

Cordice was joined by Naclerio, who had been attending a wedding and arrived still in a tuxedo.

“We usually answered these kinds of emergencies together,” Cordice later noted.

As they studied the X-rays, the two surgeons saw that King had come very close to never going anywhere at all and remained in grave danger. They summoned all their combined abilities to save him, just as they did with every patient. Their effort was in keeping with the same ultimate tenant of equality observed by the two cops who had carried King from the store and now stood protectively nearby; a life is a life.

“We had done many trauma cases, that is injuries to the chest,” Cordice would recall. “We felt the same kind of pressure and urgency in dealing with Dr. King as we did in all these other cases.”

Gloved African-American hands and gloved white hands worked expertly together as the two surgeons made one incision between the third and fourth ribs from the top and a second. They made a second, shorter incision at the end of the first one. They then inserted a rib spreader. King’s aorta became visible.

The point of the weapon was concealed by the sternum that it had penetrated with such surprising force. The surgeons confirmed by exploring underneath with their fingertips that it was exactly where the x-ray showed it to be, its still-potentially deadly sharpness vivid to the touch.

As reported in the book When Harlem Nearly Killed King by Hugh Pearson, the hospital’s chief of surgery, Aubre de Lambert Maynard entered and attempted to pull out the letter opener from King’s chest. He cut his glove on the blade and stepped for a replacement. Cordice affixed a surgical clamp to the blade to accord a grip on it.

“Look, if you’re going to pull on it, pull on it with this,” Cordice is said to have told Maynard when he returned.

Maynard reportedly ignored Cordice and removed the clamp. Cordice put on another one only for Maynard to remove that as well. Cordice put on a third clamp.

“Go on, take it out,” Cordice is said to have told Maynard.

Maynard left the clamp in place and managed to pull out the blade. He left Cordice and Naclerio to close up the incision while he went to announce to the gathered officials and reporters that the operation had been a success.

Cordice and Naclerio later stood silent at a press conference while Maynard gave an erroneous retelling of the surgery, an account that included an innovative procedure that had not in fact been performed. Maynard placed himself at the center of the action.

“He decided that it would be better if he assumed principal role here in spite of the fact that he did not actually do the surgery,” Cordice told WNYC many years later. “He would adopt the principle role in favor the publicity that would naturally follow. Of course we were not going to challenge him because actually he was the boss.”

Maynard subsequently told ever more elaborate falsehoods and presented himself ever more dramatically as the man who saved King. Cordice and Naclerio just continued doing their work, treating patients who were no less important to them for being less celebrated and often unable to pay.

“I remember people coming in with a cake to pay the bill,” recalls Cordice's daughter, Marguerite. “A good cake, with coconut shavings. People paid what they could.”

Her deeply humble and soft-spoken father seemed surprised when she suggested to him that he had influenced the course of history when he operated on King.

“It was his job," Marguerite Cordice says, “what he was trained to do, meant to do.”

She recalls that her father was aghast when somebody asked him if he had treated King differently than he might another patient.

“What? Of course not!” he replied.

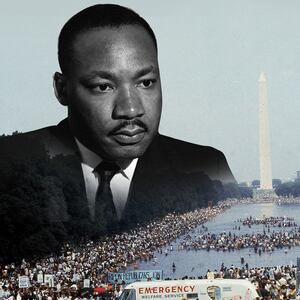

King went on to deliver his “I Have a Dream Speech” at what he rightly declared to be “the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.” He imagined aloud a time when the races would work together. And it is remarkable to think he never would have lived to speak those words were it not for a Black cop and a white cop working together, followed by a Black surgeon and a white surgeon working together, thinking of neither their own race nor of the race of the man who needed their help; humans focused only on saving a fellow human.

In another speech, this in Memphis in April of 1968, King spoke of his brush with death in New York. He recounted signing books at the department store when a woman approached.

“The only question I heard from her was, ‘Are you Martin Luther King?’” he recalled. “And I was looking down writing, and I said, yes… Before I knew it, I had been stabbed.”

He went on, “I was rushed to Harlem Hospital. It was a dark Saturday afternoon. That blade had gone through, and the X-rays revealed that the tip of the blade was on the edge of my aorta, the main artery. And once that's punctured, you drown in your own blood, that's the end of you.”

He said it was reported afterwards that he might have died if he had sneezed. He recalled one of the letters he received at the hospital.

“I'll never forget it. It said simply, ‘Dear Dr. King, I am a ninth-grade student at the Whites Plains High School.’ She said, ‘While it should not matter, I would like to mention that I am a white girl. I read in the paper of your misfortune and of your suffering. And I read that if you had sneezed, you would have died. And I'm simply writing you to say that I'm so happy that you didn't sneeze.’”

King now continued, “I want to say tonight that I too am happy that I didn't sneeze because if I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been around here in1960, when students all over the South started sitting-in at lunch counters.

“If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been around here to 1961, when we decided to take a ride for freedom and ended segregation and interstate travel.

“If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been here in 1963. Black people of Birmingham, Alabama aroused the conscience of this nation and brought into being the Civil Rights Bill.

“If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have had a chance later that year, in August, to try to tell America about a dream that I had had. If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been down in Selma, Alabama to see the great movement there.

“If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been in Memphis to see a community rally around those brothers and sisters who are suffering. I'm so happy that I didn't sneeze.”

He spoke of the death threats that had welcomed him upon his arrival in Memphis.

“Well, I don't know what will happen now,” he said. “We've got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop, and I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place, but I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will, and He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over, and I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.

He said words that would stay with everybody who heard them.

“And so I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

The following day, King was struck by an assassin’s bullet as he stood on a motel balcony. Even the most quick-witted cops and the most skillful surgeons could not have saved him.

A riot erupted in Harlem, and Romano was among the cops who found themselves in the midst of it. One of his fellow officers called out to him.

“Would you go tell them what the hell you and Al did?”

Anybody who was seriously injured had a chance of being treated by Cordice and Naclerio. Maynard continued to claim credit for saving King until his own death in 1999 at the age of 97. Naclerio had already died in 1984, at 67.

Cordice died just last month, on December 29, at 94. He had been honored in 2012 by Harlem Hospital for a long and distinguished career in which he helped save King and so many others. He had reported that he felt as if all his training had been leading up to this recognition, as if he were just a vehicle for such accomplishments.

“One of those things,” the humble giant then softly said.