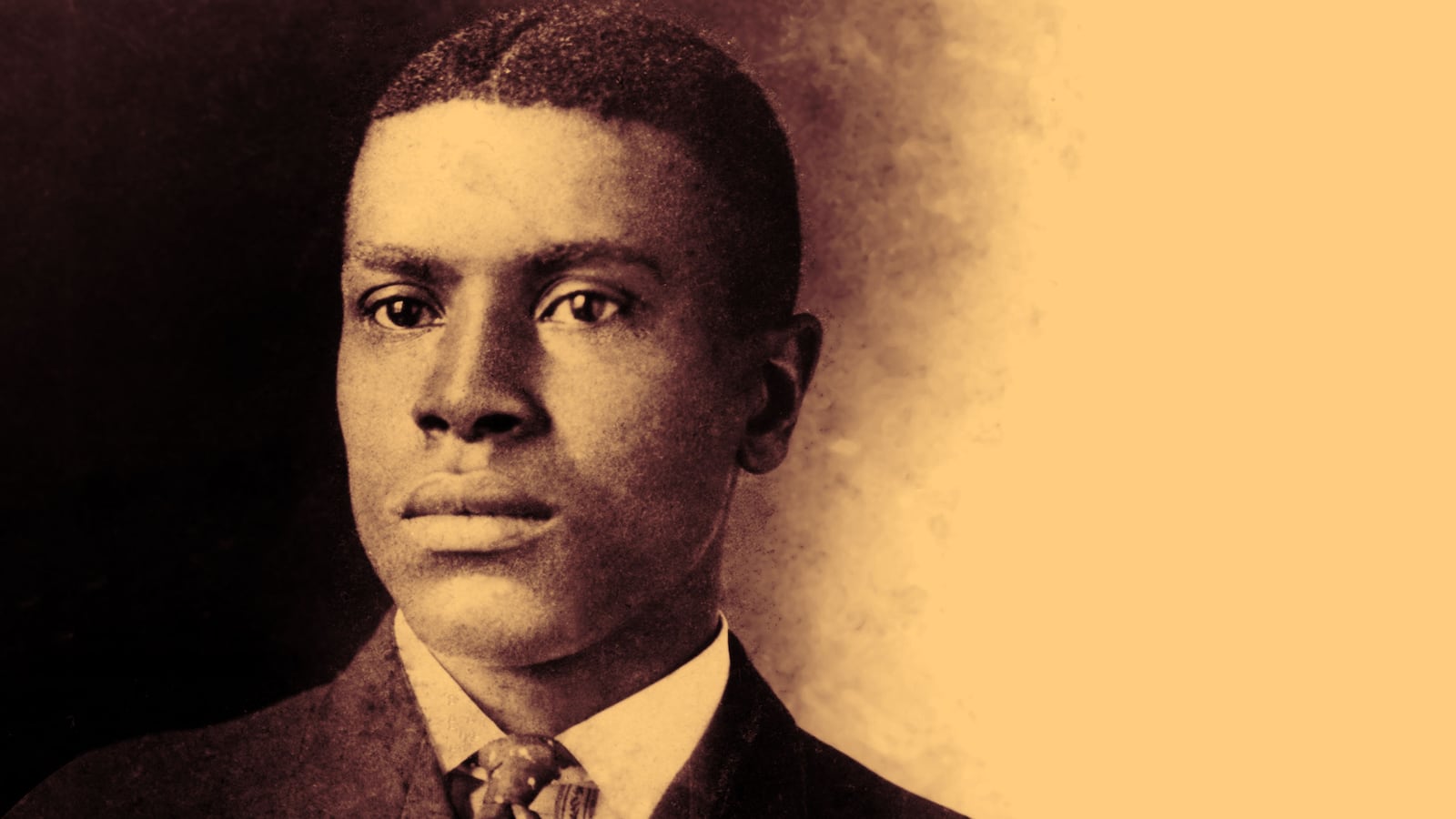

The grandson of slaves, Oscar Micheaux made 44 movies, becoming the “Cecil B. De Mille of Race Movies,” and the “Czar of Black Hollywood,” inspired by that obnoxiously racist film from 1915: Birth of a Nation.

As optimists, Americans usually treat inspiration as positive, but fear and fury motivate too. This Oscar who deserved an Oscar but never got one, turned watching Birth of a Nation into the birth of his movie career. And he refused to be shackled by the limitations all Black people endured during what we should call the Awful African-American Purgatory. Living from 1884 to 1951, he was sandwiched into that black state of suspended political animation—post-Civil-War pre-Civil-Rights—when Black freedom wasn’t completely denied but not yet achieved. While defying racism, Oscar Micheaux was so upbeat, so patriotic, and so successful, the historian Dan Moos calls him a Black Turnerian. That label embodies the optimism, pragmatism, and nationalism the late-nineteenth-century historian Frederick Jackson Turner found in the American frontier.

Micheaux’s birthplace, Murphysboro, Illinois, in 1884, and upbringing on a Kansas farm with ten siblings, set him up to be a middle American. But his adopted hometown of Gregory, South Dakota, which celebrates his legacy with an annual festival, reflects the frontier pioneer he chose to be. When he was 21 he was already homesteading 160 acres in South Dakota. Tough and ambitious, he found acceptance out West—neighbors complimented him as one of them, by calling him more South Dakotan than Black.

A natural story-teller and self-promoter, he realized he preferred writing to farming— especially after drought dried up his land. His novels mostly described a young Black pioneer’s adventures in the untamed yet surprisingly welcome wilds of South Dakota.

Then as now, writers struggled to find readers. That quest stirred Micheaux’s entrepreneurial spirit, catapulting him from the world of words to the worlds of entrepreneurship and images, and from one quintessential American platform—the West—to today’s defining American platform—commercialized pop culture.

Back in the Dakotas, Micheaux became the door-to-door cowboy salesman. Not trusting publishers, he established his own publishing company. Trusting his own salesmanship, he sold his first three—of seven—autobiographical novels to his neighbors one-by-one, from farm-to-farm: The Conquest in 1913, The Forged Note in 1915, and The Homesteader in 1917.

A restless, all-American go-getter, forever looking for new horizons, even while trailblazing his latest frontier, Micheaux leaped from forgettable pioneer novelist to history-making pioneer movie-maker in 1918. The vicious but vivid Ku Klux Klan-infused movie The Birth of a Nation, gave him his “Aha” moment. He immediately appreciated movies as a moving story-telling medium, absorbing viewers into worlds producers produced.

In 1918, the Lincoln Motion Company, co-founded by an African-American actor Nobel Johnson, proposed making The Homesteader into a film. Instead, Micheaux decided to make the movie himself. The result was a series of firsts. First, what historians now consider “the first full-length feature film written, produced, and directed by an African-American.” Second, the first of Micheaux’s 44 films. And third, the first all-Black cinematic eco-sphere independent of Hollywood: The Micheaux Film and Book Publishing Corporation, founded in 1918 in Chicago. Lincoln Films, the William D. Foster Film company, and the Colored Players Film Corp were among the key players in a whole flowering of “Race-Films”—movies made before World War II by Black people, starring Black people, about Black people to entertain Black people.

At a time when Hollywood erased them or mocked them, African-Americans emerged as three-dimensional characters in Micheaux’s two-dimensional detective stories and schlocky romances. Homesteaders grossed over $5,000 – an impressive sum. Micheaux’s Henry-Ford-type instinct with his novels – to control the process from start to finish – now shaped his movie-making. He worked with a corps of actors, favoring one leading lady, Evelyn Preer. Together, they developed the kind of auteur-actor dynamic that once made so many delight in watching Diane Keaton or Mia Farrow star in Woody Allen films – back when most viewed Allen as legendary director not creepy predator.

While entertaining audiences, Micheaux broadcast significant messages. He would say, “I have always tried to lay before the colored race a cross-section of its own life, to view the colored heart from close range.” Within Our Gates refuted D.W. Griffiths’ Birth of a Nation in 1920, showing the horrors of racist lynchings while using an attempted rape to highlight white Southerner’s horrific hypocrisy: lusting after Black women they dehumanized. Body and Soul introduced perhaps the first Black celebrity actor-activist, Paul Robeson, in 1925.

Micheaux pioneered and wrote in his twenties. He made silent movies in his thirties. And forever pushing, innovating, and pitching, pitching, pitching, Micheaux faced two final frontiers in his forties. In 1931, three years shy of turning fifty, his movie The Exile, became the first full-length sound movie directed by an African-American.

Still, Micheaux and his films remained ghettoized. Finally, in 1948, The Betrayal became the first Black film distributed to white theatres. Tragically, it ended up being his last film. Three years later, still peddling his stuff on the road, this time in Charlotte, North Carolina, Micheaux died of heart disease. The stress this driven control freak generated, through two marriages, two bad bankruptcies, and multiple careers, did him in.

Those of us raised back when the civil rights crusader Martin Luther King – and the ugly Jim Crow Southern segregation system -- were still alive and kicking, often learned about two clashing African-American role models. W.E.B. DuBois was the radical, the rebel, the prophet denouncing American racism as reflecting larger American diseases. By contrast, George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington were the patriots, the pragmatists, pulling themselves and “their people” up “by their bootstraps.” These angels of “uplift” would never kneel during the national anthem. They refused – as Washington put it -- to “allow our grievances to overshadow our opportunities.” They lived what King later preached, pushing the American system to treat them in a way that affirmed American ideals rather than violating them.

Unfortunately, by dying three years before Brown v. Board of Education, Oscar Micheaux lived in relative obscurity. He was far less well-known among whites than the man whose career he launched, Paul Robeson.

Today, books recount his exploits, films document his life, stamps honor him. The Producers Guild of America considers him “The most prolific Black – if not most prolific independent – filmmaker in American cinema.” Others call him “the father of African-American cinema.” Since 1987, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame carries his name.

These honors weren’t acts of historical affirmative action. They were affirmative acts of historical reclamation, giving Hollywood’s first Black director his proper place as a real pioneer turned celluloid trail-blazer, paving the way for future Black and white people alike. His tombstone ends his stirring life story with the perfect Hollywood tag line: “A man ahead of his time.”

FOR FURTHER READING

Dan Moos, Outside America: Race, Ethnicity, and the Role of the American West in National Belonging, 2005.

Oscar Micheaux, The Homesteader: A Novel, 1919.

Patrick McGilligan, Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only: The Life of America’s First Black Filmmaker, 2008.

Pearl Bowser & Louise Spence, Writing Himself into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audiences, 2000.