In a little-known chapter of World War II, thousands of African-American troops trained to fly barrage balloons, defensive weapons used to protect Allied soldiers from dive-bombing enemy planes during the D-Day invasion. This is their story.

Part 2: Omaha Beach, France

William Garfield Dabney plunged from a flat-bottomed metal boat into waist-deep water holding his rifle over his head, staggering toward the Normandy coast. He breathed in a bitter mix of gasoline and cordite as his boots touched ground on Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944. Enemy guns strafed the sand around him, sip sip sip sip. Hot metal struck Dabney's leg. The Army corporal quickly taped the wound and kept going.

A barrage balloon the size of a small car had been clipped to Dabney's belt. Now it was gone. In the days leading up to D-Day, when the largest armada ever assembled steamed toward occupied France, Royal Air Force crews pumped hydrogen into thousands of balloons in England and then tethered them to ships for the journey to France. The silvery spheres formed a curtain in the sky, protecting the men and materiel from dive-bombing German planes. The balloons, anchored to the ground, had flown like kites over cities like London and Tokyo. They bobbed over defense plants, Navy bases and other targets along both American coasts.

Now the balloons were going to war, armed with small bombs attached to steel cables. An enemy plane that snagged the cable risked crashing, or worse. For the next 140 days, the balloons would fly over Omaha and Utah beaches, and follow the Americans as they liberated ports and towns along the coast. The 621 African-American troops charged with raising them were members of the segregated 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, the only black combat unit at D-Day.

In the early hours of June 6, the men of the 320th piled onto more than 150 landing craft alongside infantry soldiers, amped up for a battle that Allied commanders hoped would be the turning point in the war. They were the first African Americans ashore. "It seems the whole front knows the story of the Negro barrage balloon battalion outfit that was one of the first ashore on D-Day," a military correspondent wrote to the Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower's staff. Although the men of the 320th gained a measure of fame back home for their unusual mission, in the coming decades they would be mostly written out of the story of D-Day.

On the day of the invasion, the balloons flyers were slated to land mid-morning. Like Dabney, two weeks shy of his 20th birthday, many of the men carried balloons with them. The idea was to heave the balloons to shore, already inflated, until hydrogen stocks were sufficient that the men could inflate them on the beach. A balloon shot down would be quickly replaced, maintaining a line of defense. But nothing went as planned on D-Day. Soldiers landed far off course, got separated from their companies and scattered. Early morning bombing runs had failed to take out German artillery nests tucked in the bluffs hulking over Omaha. The thousands of young GIs coming from the sea made easy targets. So did the balloons.

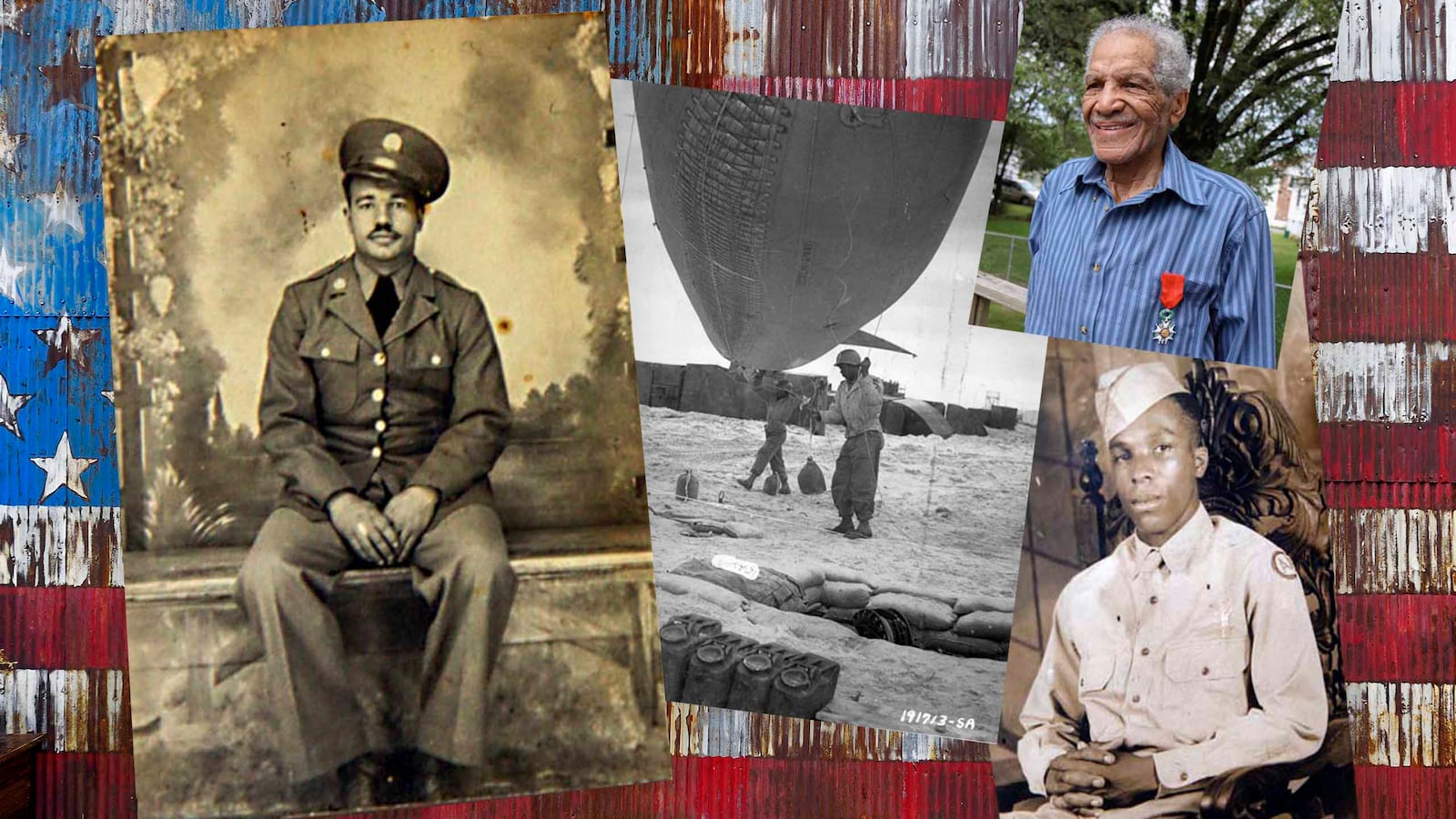

William G. Dabney wears the French Legion of Honor medal he received in June 2009.

Courtesy Linda HervieuxBill Dabney was a high-school student in Roanoke, Va., when he persuaded his grandmother to sign his enlistment papers. Now he was a sergeant in charge of getting himself, his men and that gasbag to the beach. He couldn't worry about the missing balloon—it was time to save himself. Dabney zig-zagged across the sand, desperate to avoid the treacherous “Bouncing Betty” mines buried there. He raced to dig a foxhole with the entrenching tool the Army gave them. Other men chucked the little shovel and cleared gobs of sand with their helmets. "It didn't take you long to dig a hole when you were getting shot at," Dabney told me 65 years later.

Into the fury, the boats kept coming. Sgt. George A. Davison sought cover behind the steel ramp of his Landing Craft Tank as bullets pinged the flip side. In the water, bodies were "being blown to bits, parts of men flying through the air like birds,” he wrote years after the war. Back home, Davison, 22, had been a jackhammer operator in Waynesburg, Penn. His parents had three blue stars in their window, one for each of their boys in the Army. Their oldest, Frank, a sergeant, would land in Normandy with the 515th Port Battalion a few weeks after D-Day. The brothers would meet by chance in August.

A motor launch pulled up beside Davison’s LCT. A man with a megaphone hollered, "Hit the beach!" The launch passed two more times before the ramp finally fell. "Guys were screaming 'Let's hit it, men, give 'er hell!'" Davison wrote. They didn't expect the water to be so deep. Davison grabbed onto back of a truck just ahead of him as it rolled off the ramp. The truck sunk, and Davison let go. At 5-feet-8, he plunged into the 56-degree surf, the crippling pack on his back dragging down his 180-pound frame. It was a strange time to reflect but Davison remembered the booming warning Brig. Gen. E.W. "Big Ed" Timberlake, commander of the 49th Antiaircraft Artillery Brigade, had given his men back in England: “Keep your gun dry … and don't s*** your pants.”

As machine-gun fire thwacked the water around him, Davison paddled toward shore. A wave gave him a push and his feet touched ground. Relief. Davison’s solace was short-lived. All around, men were cracking. Some crouched in the surf, clutching obstacles, now underwater, put there by the Germans to shred them. Many were too scared to move. Others sobbed, and some screamed. One infantryman spent his last moments on his knees, clutching rosary beads, praying.

George A. Davison landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day as machine-gun fire thwacked the water all around him.

Courtesy Bill DavisonDavison ran for the shingle, a sloping embankment of chunky stones that provided cover from the relentless fire. "I took a place between two men,” Davison wrote. “Nobody said anything to each other, just laid there eating that earth.” The shingle, it turned out, was no place to stay. Shells rained down, and one hit a man close to Davison. Covered in guts and blood, Davison lost it, running in circles. A soldier popped his head out of a foxhole. “Get in here,” he shouted. Sense returned to Davison. "I made a couple of giant steps," he recalled, "and rolled in the foxhole."

Davison and his balloon crew were the only black men aboard their landing craft packed with troops from the 1st Infantry Division—“Big Red One”—battle-hardened fighters who had already done landings in North Africa and Italy. The 320th men peppered the infantrymen with questions, and Davison recalled the “schooling” they got back was much appreciated.

After an Army experience pock-marked with bitter racism, segregation and violence in a southern training camp, the black troops were surprised when the white soldiers answered their questions. And they were nice about it, too. They were, Davison wrote, the "best group of men we had come in contact with anywhere." Even the ones, he noted, with southern accents.

Arthur Guest landed on Utah Beach on D-Day. Sheltered in a foxhole, he said German shells fell "like raindrops."

Courtesy Linda HervieuxOn Utah Beach, 15 miles to the west, Sgt. Arthur Guest, 23, huddled in a foxhole as the shells fell "like raindrops." Guest, who grew up dirt poor—"just above the slavery line"—on a rented farm in Berkeley County, South Carolina, wasn't scared of dying. "I thought I would be better living in the Promised Land," the future preacher told me.

Three men in the battalion died in the D-Day landing, and many others were wounded, including a young medic named Waverly Woodson, Jr. One of the first 320th men ashore, Woodson set about saving scores of drowning and wounded men. He was nominated for the Medal of Honor, though he didn't receive it. No African Americans did during World War II.

In the days and weeks after the invasion, the 320th men were on alert, watching for enemy planes. As many as 143 balloons floated 2,000 feet above the beaches. Pilots were terrified of the balloons and the small bombs they packed. "Now and then a Jerry pilot takes his chances," one newspaper correspondent wrote, describing how one plane snagged a wing on the balloon's steel cable and crashed.

A private from Okolona, Mississippi, recalled with flair how the balloons worked. "If a Nazi bird nestles in my nest," Cleveland Hayes told a reporter for the Chicago Defender, "he won't nestle nowhere else."

More newspapermen came to interview the balloon flyers, as their reputation spread. The balloons "confounded skeptics" by "keeping enemy raiders above effective strafing altitude," Stars and Stripes reported. In the 1998 film Saving Private Ryan, the balloons can be seen bobbing in the distance, yet there are no black soldiers depicted. It is a sore point among black veterans.

This is the only known image of the 320th on Omaha Beach in June 1944.

Courtesy National ArchivesIn recent years, there has been an effort made to remember the contributions of the 320th. There is a panel commemorating the balloon flyers at the American Cemetery in Normandy, and the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture recalls the 320th as part of its World War II remembrance.

As for the Medal of Honor denied Woodson, his widow, Joann, is working with the office of Maryland Sen. Chris Van Hollen to obtain the award, the nation's highest decoration for valor. So far, the Army has refused to support her, citing an absence of records. But with the 75th anniversary of the D-Day invasion approaching next June, and Americans keen to remember heroes like Woodson, Joann Woodson, 89, is praying for a breakthrough.

"I still have hope they will at least recognize him," she said last week, "to the day I die."

Earlier: Learning to fly balloons, and survive, in Jim Crow America.

Linda Hervieux is the author of Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day's Black Heroes, At Home and At War (Harper). For more on the men of the 320th, go to www.lindahervieux.com.