One of the earliest, most salient conflicts in the new Starz drama, BMF—which stands for Detroit’s infamous Black Mafia Family street gang founded by brothers Demetrius “Big Meech” and Terry “Southwest T” Flenory—is who sets the market price for the blood of our kin. Do we measure it as an eye for an eye, will a pound of flesh suffice, or does it require complete amputation? This is the conundrum that sits on the tearful face of patriarch Charles Flenory (played by Russell Hornsby), as he gazes into the well-baby nursery of a Detroit hospital.

Meech (played by Big Meech’s actual son Demetrius “Lil Meech” Flenory) and Terry (Da’Vinchi) have just gotten a taste of the glamorous street life that smacks of Ciroc, copper and steel—a bloody trio that Charles and his wife Lucille (Michole Briana White) have done their damnedest to shield their kids from—and not through hate for the streets. This was a feeling—the indelible tug and pull of the fur-coated dope boys who’d have floor seats at the most upscale functions and the tacit respect of those in their orbit—that could only be reconstructed on the screen by a cadre of artists with a direct connection to the family and to the city of Detroit.

“Season one is about Detroit,” showrunner and Detroit native Randy Huggins explains to The Daily Beast. “It’s as much about Detroit as it is about the Flenorys. What was happening in Detroit created Meech and Terry, compelled them to go out and do the things they did. I’m a Detroiter so you know i’mma represent it.”

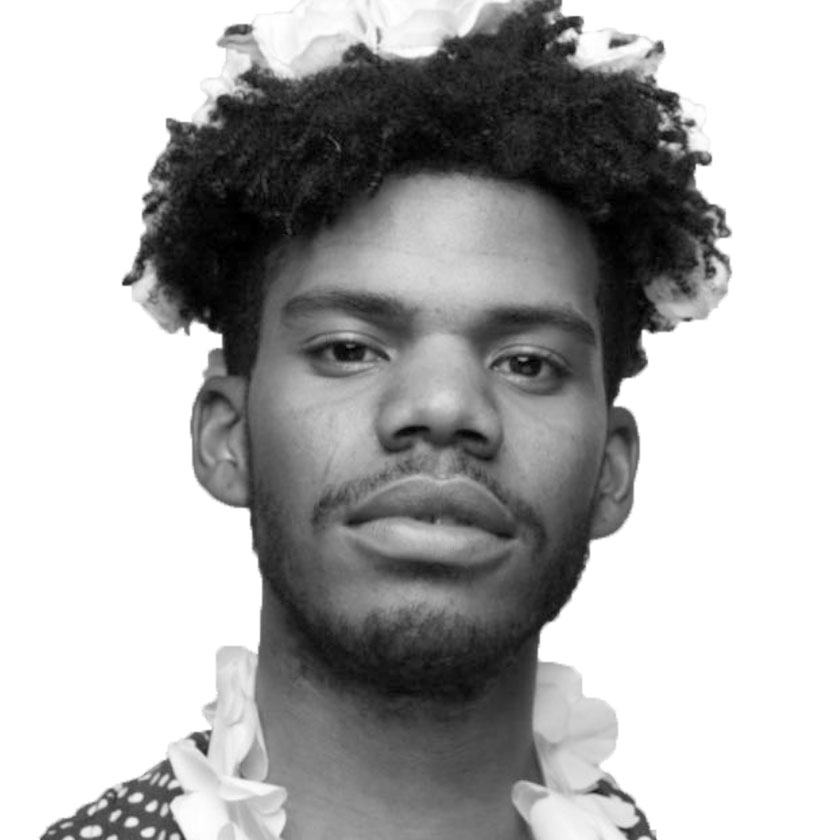

Randy Huggins and 50 Cent at the BMF world premiere at Cellairis Amphitheatre, Lakewood, Sept. 23, 2021, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Paras Griffin/GettyThe Motor City is, indeed, its own character within the show—it has its own desires, its own interests, its own version of morality that, at times, can be sparklingly spiritual and crassly bloody. This is the Detroit the Flenorys knew and understood. It was a place where the idea of a two-parent nuclear family producing one of the most successful street-business conglomerates isn’t so farfetched.

In retelling and dramatizing the story of the Black Mafia Family, Huggins’ experience within the city was paramount in gaining and sustaining the trust of Meech—who is due to be released from an Oregon prison in 2023—and Terry. Not only are Huggins and the Flenory brothers close in age but “culturally we connect, culturally we speak the same language. One of the places they hung out most was this gym called Saint Cecilia’s. It’s like our Rucker Park. I used to play basketball growing up so you know I was there to watch the basketball players but the dope boys would be there betting on games. It was just the place to be. I was in that, I was there.”

No doubt the dope boys were drippy—flash and Black exuberance have been fundamental to local Detroit culture from the Great Migration days, so it’s no surprise Huggins found himself marveling at how men like the Flenorys carried themselves. “A lot of the fashion they wore, I want to wear. My mother wouldn’t buy them for me,” he says with a down-home chuckle. “But I would aspire to it.”

Veneration for the city bleeds through BMF. The Flenorys frequenting night haunts like Cheeks, The Shelter or City Club with gleaming lights reflecting off Lil Meech’s designer shades, his ankle-length fur coat fluttering in the night wind, strengthened their mythologies without the two brothers ever having to mention their drug affiliations. To shed light on their origin, their history, Huggins and his crew of talented artists needed to learn what made these men who they are. “What I had to do was forget the shit I’d heard around me coming up. I heard so much and it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh.’ I’m not trying to make this a salacious show. I want to tell this story as authentically as I possibly can but also tell a family story. The family they were brought up in gave them the values they instilled in the family they brought up in the street.”

There’s ample evidence that, for the Flenory brothers, spirituality and kinship worked hand in hand with running a tight organization. In her book on the rise and fall of the BMF clan, South editor at ProPublica and former Atlanta crime reporter Mara Shalhoup recalls a moment where, after a death in the family, a mid-level dealer masqueraded as Meech while trying to calm down a fellow family member. In that conversation, he mentions apologizing to the dealer’s mother, a key detail that so embodies Meech’s leadership style that he got away with it pretty easily. That kind of care, whether it’s read as genuine or not, endeared the family to Meech and Terry’s causes. In talking with Meech through the barriers of a prison, Huggins mentions that one of the biggest things he learned was that Charles Flenory was a real man. “He used to tell his boys, I love you. He would kiss and hug his boys. Their relationship was paramount.”

There were plenty of traps the show could’ve fallen into. In telling a “true story,” there are a mess of facts, narratives, and rumors that could complicate the filming process. The ending of the Black Mafia Family includes the Flenory brothers becoming estranged—a potentially hairy situation when dealing with real, actual people in violent situations. While Meech seemed like the center of the story, Huggins tactfully approached both brothers. “I had already had the game from Meech,” Huggins explains, “But they were a tandem. It’s like the Lakers’ story: you can’t tell it all from Shaq’s side or Kobe’s side, you gotta hear it from both. But the benefit was, I got the game from Meech so I already had what I wanted to tell and was able to go to Terry with specific questions.”

In conveying that relationship, Lil Meech, Da’Vinchi and Hornsby carry an emotional vitality that bursts through the screen. Hornsby was the first. “I needed someone to set the tone on how the show was gonna go,” Huggins explains. “So, when he shows up to set he knows all his lines, your lines, and everybody else’s. He’s dressed, he’s ready. But with the actors, Tasha [Smith] gets a lot of credit. She used to work with the actors separately before they even came to set.”

The cast and crew includes a nice mix of veterans and newcomers. The growth of Lil Meech as a performer is one highlight, and was rooted in a nearly two-year plan set forth by executive producer 50 Cent, who hooked him up with acclaimed actor and director Tasha Smith (director of BMF’s first episode). Smith then trained Lil Meech for a year and a half before shooting began. “I didn’t see it at first,” Huggins admits. “I only saw it when he did his chemistry read with Da’Vinchi and then when he cut his hair I was like, ‘Oh yeah, he definitely got it.’”

Huggins talks about the cast and crew like a coach, giving kudos to the men and women of his crew who’ve helped him along the way. “I think it’s very important on a team that people listen to each other. And that’s something we did.”

If Huggins sounds like the perfect team coach, it’s probably thanks to his time as a former all-state football star in Detroit. “In our industry, a championship is a four-letter word that begins with an E and ends in a Y. So I led with that. Anybody that came on our show, I was like, ‘Dude, we’re trying to change the landscape of TV and win an Emmy. If you’re not about that then this is probably the wrong show for you.”

“Hopefully looking at this story, I really do hope Meech and Terry are proud. I hope all the Flenorys are proud. I hope everybody in Detroit is proud,” offers Huggins. “Obviously I want the world to be proud, but if I make the Flenorys and Detroit happy then I feel I did my job.”