On Friday, May 29, Aaliyah Jones, a 24-year-old nursing student from Kingsburg, California, shared an event on Facebook. The event, titled #WECAN’TBREATHE, announced a protest the following afternoon outside Fresno City Hall, just 30 minutes northwest of her town. Jones, who planned to go as a bystander with her local NAACP chapter, shared the event to invite friends to join. One side effect of that: her aunt saw it.

“No ALL LIVES MATTER!!!!!” Jones’ aunt replied. “Not just black lives!” Jones, whose father is black and mother is white, grew up with refrains like this from her maternal relatives. “They’ve always made racist comments,” she said. “They would say things like, ‘You’re not even that black. You’re not black, you need to act like you have some sense.’ I used to just laugh it off. I was young, I didn’t understand.”

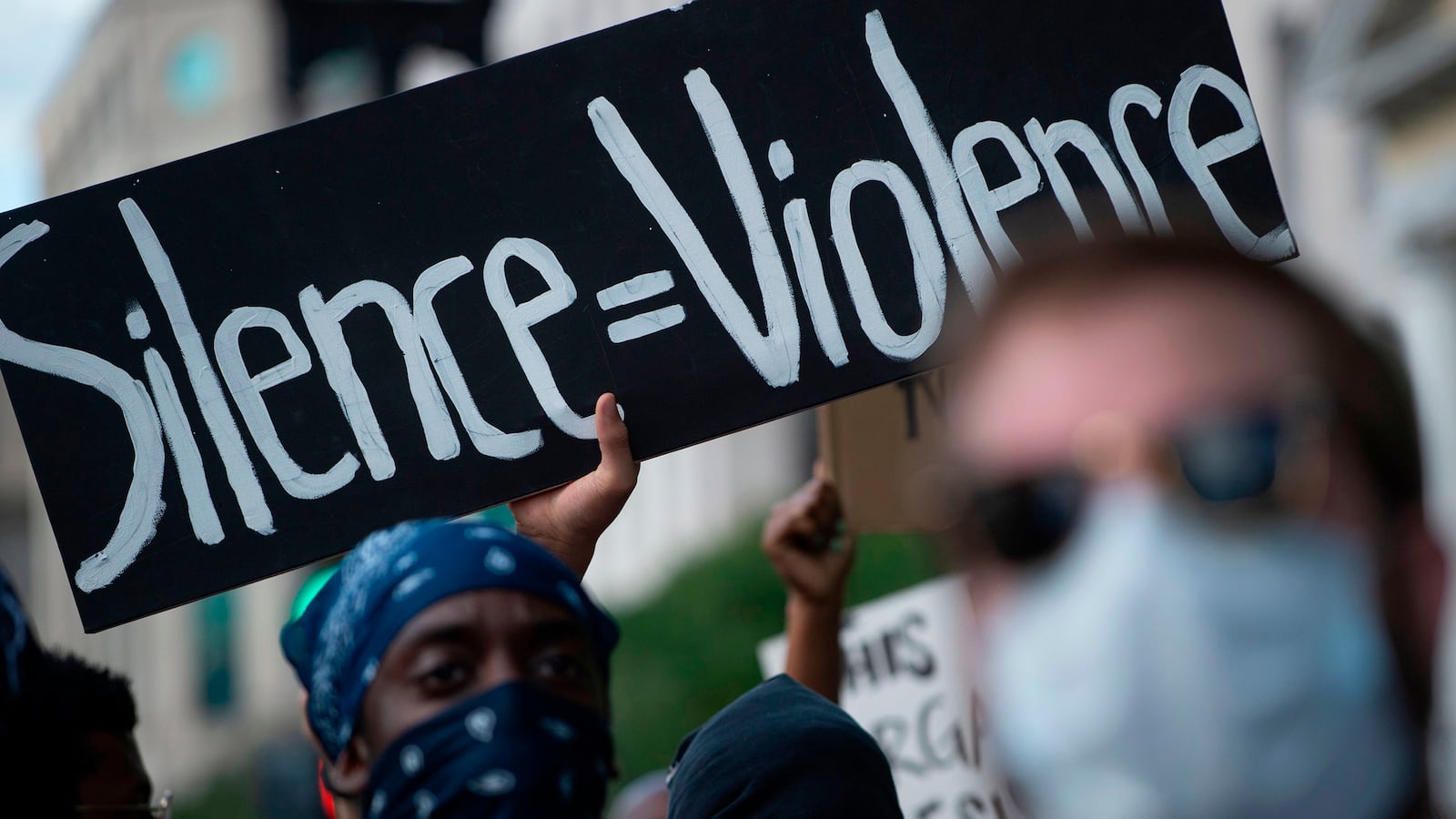

In the past two weeks, as protesters organized daily marches against police brutality, Jones’ patience began to run out. The murders of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery intensified her fear for her boyfriend, who is black, and their 1-year-old son. She tried to explain that to her aunt; the aunt blocked her. After other commenters began to pile on, the aunt messaged Jones to quash the conversation. In one of the messages, captured in screenshots, the aunt wrote, “I am racial about stupid n*****s!!! There is a difference between black peoples and n*****s!!! Clearly all the ones that are rioting are N*****S! Black people don’t stoop to that level.” Not long later, Jones stopped responding. They haven’t spoken since.

The day after the protest in Fresno, Jones found a comment thread on Twitter started by the user @allieledoux, whose display name is Alexandra. She’d tweeted a text from a cousin, announcing he planned to unfriend her on Facebook, scolding her for “defending these animals,” and trashing her mother. “The blacks are the ones ruining this country,” he wrote. “NOT TRUMP.” Alexandra told him to lose her number and never speak to her again. “If you ever speak another ill word about my mother,” she said, “there will be problems you stupid fuck.” Jones replied with her own screenshots, adding, “you are not alone.”

By Saturday, Alexandra’s tweet had been retweeted almost 122,000 times, gotten 862,000 likes, and created a kind of forum for protesters to share stories of family schisms over the protests. One user, a 21-year-old from Salt Lake City who asked to remain anonymous, shared an exchange with his dad. “I see you on TV... down there with all the losers breaking windows, throwing bricks and water bottles at police officers,” the father wrote. “This isn’t protesting... this is anarchy. Certainly my enemy…” They’d had an ongoing conflict about Black Lives Matter, the son said, but the message marked a breaking point. “Cool,” he wrote back, “want you out of my life now.”

Spencer Waites, a 24-year-old from Chattanooga, Tennessee, tweeted a message from his mom, telling him she was unfriending him, “until you get your head of your ass [sic].” She called his support for BLM “group think.” Until about four years ago, Waites might have agreed with her. He was, in his words, “very much an asinine kid,” a guy who thought Colin Kaepernick’s protest against police violence was “disrespectful.” In the past year or so, Waites began to see differently, and in January, began to write about it online. When he read about George Floyd’s murder, he began to share photos from protests, articles, and donation links. “There are lots of people back home who I grew up with, who I loved, who I would think would want to be on the side of moral standing, not on the side of the oppressor, but of the oppressed,” Waites said. “But I started to get messages from relatives, started getting into arguments. Some of my family members blocked me.”

His mom’s message stung the most. “Both of her parents are immigrants from Mexico,” he said, “it just blows my mind that she’s not seeing it. She’s not understanding it... In the Hispanic community, there is a lot of racism toward black americans. My grandmother is... pretty racist. She doesn’t like black people at all. But I don’t think my mother is racist; I just don’t think she gets it. She doesn’t understand why it’s different. There’s a difference between racist and anti-black. A lot of this police brutality—it’s racist, but it’s really anti-black.”

Addy, a 19-year-old grocery store worker from a small town in Arkansas, also shared screenshots of her parents’ messages. She had attended two protests in Arkansas, both of which were peaceful. One of them, however, had been threatened twice by white counterprotesters with guns. The first time, a white driver pulled up into the middle of the street and pulled out his AR-15; the second time, four white men brandished a firearm at protesters and yelled slurs. When she wrote about the events on Facebook, Addy received messages from her family, questioning her account. She also stopped engaging. “He literally just said the n word,” she wrote in one text. “I really don’t want to hear it.”

Her family had always harbored racist sentiments, Addy said. She grew up hearing slurs. But she partly blamed their impression of the protests on Facebook, their primary source of information. “They only see the videos of protests turning into riots,” she said, “but don’t see the firsthand accounts of people who protested peacefully and still got tear-gassed and shot with rubber bullets.”

One of the more remarkable aspects of the thread, is that nearly all of the family breakups involved Facebook—comments or messages, getting blocked or unfriended. There’s a common bit on Twitter about “checking in on Facebook,” usually followed by a screenshot of some distinctly Facebook exchange. The joke hinges on the fact that, despite their similarities, the larger platform is somehow more insular, its billions of users siloed into smaller communities. It’s an interpersonal junkyard, where users can pop in on regional reptile groups, high school classmates’ weight loss journeys, some aunt’s Impact-text, Bible Spongebob memes. But the insularity makes it also more familial, the online equivalent of a Thanksgiving table. As activists revolt against entrenched police power, the platform claiming to “bring the world closer together” also lays bare what sets families apart.