When the cops turned up on the evening of April 6, 2012, George von Bothmer needed to be absolutely sure: “Are you the real police?” he asked. They were. Two officers stood at the door of von Bothmer’s suburban home in the posh town of Lake Oswego, Oregon. They were dressed in uniform, each having arrived in a marked patrol car. More were on the way.

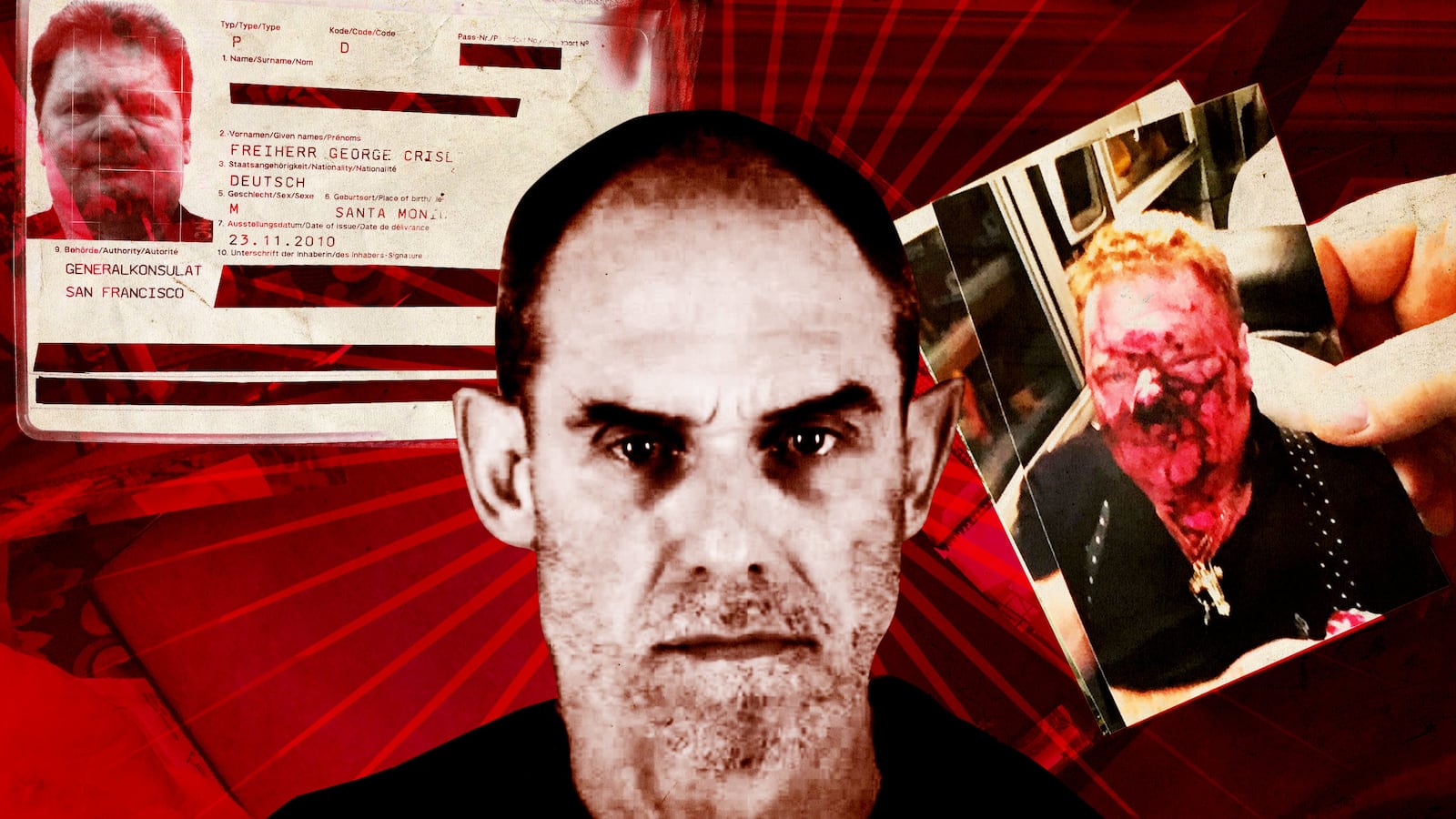

A portly man with receding red hair, von Bothmer was bleeding from a messy wound, blood streaking across his nose and mouth and dripping down his chin toward the lime-sized gold cross that he wore on a necklace. His waist, wrists, and ankles were wrapped in duct tape. Behind him in the living room, more tape littered the floor. Twin holes traced the path of a bullet through a nearby lampshade and into the wall.

The officers stepped inside. Two teenagers were also there, both pulling tape from their wrists, feet, and necks. One of the cops told them to stop. It was evidence, he said.

While the police waited for detectives to arrive and tried to keep the crime scene undisturbed, von Bothmer started in on two stories. The first was the story of two gunmen who, disguised as federal marshals, had just tied him up and robbed him, along with his 17-year-old daughter Annette (Netta), and her boyfriend, William Laitta. The second was his own story: that of a German baron with an illustrious family history and a museum’s worth of fine art, antiques, and jewels. The stolen jewelry alone, he said, was worth as much as $1.5 million.

Despite his wounds and the natural agitation of a man who has just been robbed, von Bothmer’s manner was courtly. He peppered his recollection of events with a conviviality that people who knew him would have recognized as mainstays of any conversation with the man they called “the Baron”: “Thank you, sirs,” and “You are so kind,” and “God bless you and yours.” The words contrasted with his rattled disposition and the condition of his face. As he spoke, he worked his way back and forth across the floor, marching with such visible intensity that the officers worried he might faint. They signaled the paramedics to escort him to an ambulance outside.

“I’m a German citizen,” he called on his way out the door. “I have diplomatic immunity!” It was an odd remark for a crime victim, odd enough that an officer noted it.

Next, the police separated the shaking daughter from the teary-eyed boyfriend and began their interviews. The story the teens told went like this: Two men wearing hats, dressed in dark clothes, and wielding badges had come to the door asking questions about a semiautomatic weapon. One of them was a young guy, the other significantly older. The Baron told them he didn’t own any such gun and then, in typical fashion, invited them in for tea.

Once inside, the two men suddenly shoved him and demanded a key or a combination to a safe that, according to the Baron’s daughter, didn’t contain anything but passports. When the Baron didn’t produce a key or a combination, the older man cracked him in the face with a pistol that accidentally fired.

Whatever steadiness the assailants may have had was then gone. The younger man began waving a handgun about. He sounded anxious, trying unsuccessfully to calm the three stunned victims. “Don’t worry. We’re not going to kill you,” he said, right before the other, more menacing man threatened to kill all of them.

The older guy was haggard, worn-out-looking, and had the raspy voice of a longtime smoker. At one point he put a gun to the Baron’s head, then Netta’s, then marched the boyfriend, William, upstairs on a hunt for a key to the safe while he counted down the seconds left in William’s life. Failing to find a key, or a safe, the attacker steered William back to the living room and repeated his promise to kill everybody.

The younger man then bound the three captives with duct tape. He wrapped Netta around the head. Then he proceeded to move about the house, grabbing shiny things and stuffing them into garbage bags. After discovering and bagging the stash of jewelry in a cabinet, he and the other man headed for the door. They warned the Baron and the others not to move for 10 minutes and not to call the police. Two minutes after they left, the younger man flew back into the house to retrieve a bag he had left behind.

During their interviews with the real police, each victim said the attack wasn’t random. It was a setup. The Baron said so while seated in the ambulance. Netta said so after taking a few minutes to compose herself in the upstairs bathroom. And William said so after a phone call with his father.

They all said that if there was anyone who had it out for the Baron, it was Bill Sikkens, the Baron’s former business partner. Sikkens was strange, crazy even, they told the police. They said he claimed to have ties to Blackwater, the controversial private security firm. They also alleged that he was bipolar or schizophrenic, or both, and had stopped taking his medications. The relationship between the Baron and Sikkens had deteriorated to such an extent that the Baron had recently filed for a restraining order.

By the door to the ambulance, Det. Lee Ferguson listened closely to the Baron’s breathless account. A slim man with close-cropped hair and a preference for sport coats, Ferguson was a decorated cop who had won Officer of the Year a few years earlier. He had a distaste for speculation and a knack for stitching facts into reasonable conclusions, no matter how bizarre those facts.

Right away, Ferguson noted incongruous details: the Baron’s wife, who had rushed home from work, climbed down from the ambulance smiling after a few minutes alone with her husband, even though he was still covered in blood. Then there was the Baron’s frantic roll call of valuables, claims of priceless artwork and antiquities that, even to a cop, didn’t sound like they belonged in a suburban rental house. There was a little too much certainty about Sikkens’ guilt, too, along with inconsistent comments about a safe, and of course, the victim’s non sequitur pronouncements of European this-and-that. It was a lot to sort out.

On Easter weekend in 2012, Bill Sikkens, 36, was sitting down for a holiday dinner with his parents in Reno, Nevada when the phone rang. It was a friend from Oregon calling. The local Fox station had just aired news of a home invasion. The victim was George von Bothmer. Are you somehow involved? asked the friend. Sikkens said he was not.

A decade earlier Sikkens—a self-described computer nerd who had few friends and a soft spot for painkillers almost as pronounced as his soft spot for European history—had moved from Nevada to Vancouver, Washington, where he joined a local Masonic lodge, eager to meet some like-minded people. One afternoon, he attended a Freemasons-sponsored fundraiser, where he met George von Bothmer. “He said he was a nobleman, a baron from Germany or somewhere,” Sikkens later recalled.

The two began talking and struck up a friendship. When Sikkens first visited the Baron’s home on Telluride Street in Beaverton, he was dazzled. While the Baron served tea and explained that he was doing foundation work for the government of Hungary, Sikkens looked around. The house was “full of paintings and antiques,” he recently recalled. Later photographs of the collection show walls crowded with artwork and downstairs spaces full of ornate furniture and glass cases jammed with old books, geodes, antique rifles, fossils, and vases. There were Oriental rugs atop the wall-to-wall carpeting, and nearly every available surface was appointed with candlesticks, plates, or silver tea sets. Art was piled up on the floor, and huge paintings hung over the windows on chains. Standout furnishings included an imposing-looking grandfather clock, a display case packed with statues, and 18th century-style chairs and a bench upholstered in lapis blue fabric.

Within a couple of years, the two men were close, and when the Baron suggested one day that Sikkens bring him into his consulting business so that they could cultivate European clients, Sikkens agreed. Their friendship grew to the point that when the Baron’s house went into foreclosure a few years later, Sikkens tried to secure a new loan. He also said he was the cosigner on a new lease for a rental, and on the loan for the Baron’s 1997 Jaguar XJ6.

For Sikkens, the Baron opened up a new world and accompanying circle of friends. There was Eric Strom, the financial investment adviser. There was John Wittrock, the Stanford-educated lawyer. There were the Baron’s graceful wife and beautiful daughters. At epic Halloween bashes, happy-hour gatherings, and afternoon tea sessions with spiked refreshments, Sikkens felt, finally, that he was part of something. The veneer of aristocracy only added to his sense of enchantment, access to a social enclave that was supposed to be inaccessible to lonely geeks from Reno. The cufflinks and crystal, the family crests and reproduction masterpieces in gold-painted frames—it was all part of a new reality in which everybody was somebody. Whether that world was real or not mattered less than what it felt like, and what it felt like was an antidote to boredom, to life’s disappointments.

In a 2012 Petition for a Stalking Protective Order filed in Clackamas County, Ore., The Baron expressed concern that William Sikkens was dangerous.

HandoutBut Sikkens’ professional partnership with The Baron proved destructive. The Baron, Sikkens believed, took money from the business, while simultaneously working to push Sikkens to the periphery. Sikkens says he sent the Baron two certified letters summarizing the allegations and demanding repayment, which the Baron took straight to a judge as justification for a restraining order. He also reported that Sikkens had threatened to attack him and that Sikkens had even killed people.

George von Bothmer’s given name is George Criser Davis. He was born in 1952 in Santa Monica, California, to Charles and Wilda Davis. In 1994 he became a Baron after a late-life adoption by an 85-year-old aunt and baroness, an American fashion model who had married a German. She died soon after, by which point George had already changed his name to Baron George von Bothmer zu Schwegerhoff.

Blueblood street cred is not actually hard to come by. Unlike the Baron, many people nowadays use their checkbooks to purchase lordships or baronies, shelling out tens of thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands, of dollars, for a title that confers little-to-no financial value but can pay inestimable dividends when one is trying to impress certain business contacts or country club members. Plus, it can be great at parties.

“My full name is on my German passport, though, which is interesting,” the Baron recently explained. “It’s difficult sometimes to get a title on a German passport. They did it, I think, as a courtesy… I’m a German citizen and I’m also a U.S. citizen. I’m also a very staunch political figure in Germany and in Europe and in the EU. My godfather, Otto von Habsburg, who created the European Union, is the father of the European Union, and of course would be Holy Roman emperor—he would have been."

When it comes to the artwork and objects decorating his home, the Baron has always thought of himself as a custodian. “They don’t belong to me. They belong to all of humanity!” he says. “I have a lot of beautiful, inherited things. One of the items that was taken [in the robbery] was the marriage crown of Pu Yi, the last emperor of China’s first wife.” Other items, he said, included priceless necklaces, sapphires, and rubies from Marie Antoinette’s mother.

The list of treasures goes on. There are the pre-war letters from Albert Einstein, for example: “So when these documents—for instance, the documents from Einstein and other scientists in the 1920s—they’re seeing this huge shift to the right, this horrible political scenario going on and my family is receiving these letters back and forth saying we need to get the scientific community out of Deutschland—get the hell out of Dodge, as the word would be used—to get these bright, good people away from the Monster, Hitler. So to my family, these documents to my family—we also had several million dollars worth of Christian Bernhard Rode etchings. He was the Rembrandt of Germany.”

When the Baron talks about himself—about his ties to royalty, about Hungary, about the castles in Germany, about how he came to possess Mahatma Gandhi’s letter opener, about the Houses of Hapsburg, Hess, and Orange, about his Fabergé egg, about how his family “built 10 Downing Street,” about any of it—his listeners, unless they are lobotomized, have questions. But the Baron has a social style that somehow defuses the will to scrutinize: talk until no one can remember what their original questions were. Bury them with words.

“My family still owns and operates museums in Europe. And all of the items that were stolen are highly documented, highly photographed, and internationally known. So this notion, I mean, the Annetta von Drose Hulstof Museum my cousins run and operate near Sbergslof, which is a big castle on Lake Constance in Switzerland—we have other castles open to the public—I mean, this is an amazing circumstance. People who ask me why am I here. Well, there were reasons that we can get into that my mother from Germany and members of my family came here. Oregon is a very pretty place. And it doesn’t have, necessarily, the baggage that exists with the old aristocracy…” What was your question again? No matter, because now the Baron is talking about how the King of Spain flew to his pregnant mother’s bedside in California to place dirt beneath her on the floor so that her child would be born on (or at least above) European soil.

One topic the Baron seems disinclined to prattle about are accusations of swindling. In the late ’90s, after leaving a job as a teacher’s aide in a Portland suburb, he and his wife moved to Victoria, British Columbia. There, in an unusual property deal, he secured a 99-year lease on a three-story Tudor—for $1.00 (Canadian!). A lawsuit was later filed by the property owners, the Anglican Church Women of the Diocese of British Columbia, alleging that the Baron and Baroness had ripped them off with “false representations,” “undue influence, fraud, substantial unfairness and unconscionable bargain,” and made off with “unjust enrichment.”

The Baron fought back, calling the charges outrageous. "It’s absurd!" he told The Oregonian in 2000. "I know who I am. My family has been around for a long, long time, and in that time we have learned the wisdom of honesty. We have learned that it is easier to coexist with a true heart." The case settled out of court a couple of years later, and the Baron and his family were soon back in Oregon.

In 2012, the Oregon Board of Psychology Examiners opened a probe to examine whether the Baron had been masquerading as a licensed therapist. Sikkens and at least one other person complained to the board that the Baron claimed to be a clinical psychologist. When his relationship with the Baron soured, Sikkens lodged a formal complaint with the state board. (A 2000 article in The Oregonian reported that many of the Baron’s former colleagues at a Beaverton school also thought he was a psychologist. When contacted for this story, a board representative said details of their investigations are confidential when the case does not involve discipline.)

The Baron also has a penchant for lawyering up. In the fall of 2010, a lawyer representing him wrote to a Laguna Hills, California law firm representing 24 Hour Fitness to provide “an opportunity for settlement without litigation.” According to the lawyer, Peter Glazer, on Nov. 28, the Baron “was walking into the yoga room at the McEwan Road [24 Hour Fitness in Tigard, Oregon] facility when he stepped on a rock or stone which had come loose from the quite unconventional flooring.” He slid and “fell hard on his back and posterior. Mr. von Bothmer lost feeling in his left leg and was unable to stand up. He was in great pain as he lay on the floor and despite his cries for assistance, it was minutes before another club member came into the room.” No one called an ambulance, though. The fall and subsequent “investigation” Glazer wrote, brought to light 24 Hour Fitness’ “negligence” when it came to “repeated problems with ‘decorative’ flooring near the yoga room.” The Baron’s lower-back bruising, nerve pain, and other medical difficulties allegedly affected him from the left shoulder to the left ankle and led to repeated doctor’s visits and $20,000 in medical expenses. Without a $100,000 settlement, Glazer wrote, “our client is prepared to file suit.” So far as anyone can tell, nothing came of the letter.

Meanwhile, word was spreading that the Baron and Baroness might not be honest brokers. Leaving Canada had not deleted the story of the Victoria property, while others in the Baron’s circle began expressing irritation and lobbing accusations of dishonesty.

In the early days of Ferguson’s investigation, the Lake Oswego detective treated Sikkens as a key person of interest. After all, the Baron asserted that Sikkens was behind the invasion, and the daughter and boyfriend had also flagged him for police. At Ferguson’s request, authorities in Reno put a car on Sikkens parents’ house right away. But over a period of days, no one came or went, and the only cars in the driveway belonged there.

As he continued digging, Ferguson found contradictory information regarding motive for the robbery: Sikkens was unemployed and had no income, suggesting he didn’t have the means to order an attack on his old partner. Struggling to make money and unable to defend himself in court against the Baron’s restraining order, Sikkens had to move back in with his parents. Indeed, the more Ferguson learned, the more Sikkens proved to be a docile homebody, not a criminal mastermind. Ferguson would later conclude: “I found no communication between Bill Sikkens and people in the Northwest in the time up to and around the incident that would have indicated he was coordinating anything. Bill Sikkens does not have the financial means to ‘organize’ a robbery.”

In the same petition, The Baron described a man so menacing that he claimed to have killed 20,000.

HandoutAbout the Baron and their protracted dispute, Sikkens is by turns bewildered and embarrassed. “The hook that got me into this is the idea that I had actually befriended European nobility,” he says. “I wanted to believe him. And he was able to do enough of a show for someone like me who didn’t really know the historical background. It looked pretty real,” Sikkens says, with all the trappings of noblesse. “And some of his pieces I think are real antiques.”

His situation, Sikkens admits, was made worse by an addiction to painkillers. The drugs turned Sikkens into a “zombie,” he says, annihilating whatever capacity he may have had to recognize a spade, let alone call one out. “I never went to review things, to see that he was dipping into the checking account of the business. I would have seen that if not for the painkillers.”

Sikkens’ story wasn’t the only thing that cast doubt on the veracity of the Baron’s account and called into question whether the robbery was really a robbery at all. When police combed through the Baron’s house afterward, they found nothing broken save for the lampshade with the bullet hole. A thin glass case had somehow survived the struggle in the living room. Upstairs, the bedroom—the one with the safe in it—hadn’t been ransacked as the victims had described; only two drawers had been pulled from a dresser. According to the police report, bottles of oxycodone and muscle relaxants were strewn around the room. There was a receipt for jewelry recently pawned for cash, a few sizeable marijuana plants growing inside one of the bedrooms, and the Jaguar that was due to be repossessed any day.

One of the Baron’s close associates told police, “George is perfectly capable of having pulled off this event.” Another former friend of the Baron’s said that when he heard about the home invasion, he thought right away that it was a fraud. Police also believed that the Baron had a penchant for using his royal status to garner financial favors. The von Bothmers allegedly had close to zero income, save for the Baroness’ wages from her job at a nearby department store, and just four months earlier, the Baron had taken out rental insurance. On top of all that, no neighbors interviewed by police reported hearing or seeing anything suspicious that day, save for the one who called police at the Baron’s request.

To Ferguson and his colleagues, a bogus robbery plus follow-up insurance fraud had to have been a possibility. How could it not? It was the most plausible interpretation of the evidence pattern, and it tracked with the sense of urgency with which the Baron, face still soaked in blood, declared his multi-million-dollar loss of property. The police never said as much, but the accusations and peculiarities surrounding the Baron, together with statements from interviewees who told the police unequivocally that they felt the Baron was capable of pulling off such a hoax, meant that any good investigator would have had to consider that scenario.

The possibility that the home invasion was a charade must have infuriated local police. As crime seasons go, spring 2012 had its demands: At the time, the FBI and several departments in the region, including Lake Oswego, were scrambling to find and arrest a bank robber responsible for a spate of recent robberies. They were closing in on an ex-con named David Ray Taylor, but the case would require all the manpower they had.

This is where things get serious. Because David Ray Taylor was a serious guy who lived by a code of sorts. He believed in mentoring young people. He believed that women should be killed swiftly and painlessly, unlike men. And he didn’t like liars.

David Ray Taylor

Lane County JailIn 1977, Taylor was sent to prison for killing a 21-year-old gas station attendant with a shotgun. He was caught when his victim used the final minutes of her life to carve the killer’s license plate number into her skin. Between his parole in 2004 and the time police caught up with him in 2012, Taylor had managed to keep out of jail. Not out of trouble, just jail. In the span of eight years, Taylor was charged with rape, sex abuse, assault, strangulation, menacing and harassment, and other offenses. In each instance, he managed to slither out of court and back onto the street.

Then the bank robberies started.

Taylor was unlike many bank robbers in that he preferred to flee the scene on a bicycle, riding to a getaway car parked beyond the view of security cameras. A small group of protégés allegedly helped with these escapes and the rest of his operation. They developed relay systems for stolen goods and safe houses for stashing and crashing. These underlings, mostly troubled addicts and petty criminals, lionized Taylor. They saw him as the baddest of bad guys, wowed by his disdain for social order and the purity of his Couldn’t give a fuck. In some ways, Taylor’s entourage was like The Baron’s: all that posturing masking a deeper wish to be someone else. In this case, though, they lacked the finery and the ability to name-check lakes and castles in Europe.

By the time Taylor and his crew robbed a ninth bank, in the spring of 2012, law enforcement was closing in. At the same time, Ferguson was still deep into his investigation of the Baron’s home invasion, running down leads despite his department’s apparent misgivings about whether a robbery had even occurred. Then in mid-May, about five weeks after the Baron’s alleged attack, Ferguson got a call from a tipster who dropped the name of a 24-year-old deadbeat: Spensir Mourey. Mourey had been bragging that he’d done the home invasion with an older partner, a guy no one would suspect because he looked like someone’s grandfather.

Ferguson and another detective began tailing Mourey and soon had evidence of an older associate, a guy who carried a butcher knife on his hip. The lucky break was a second tip, this one naming a David Taylor and mentioning that he had done hard time. Sifting through the 55 David Taylors once jailed in the state revealed a match: David Ray Taylor, convicted murderer and suspected bank robber.

Things moved quickly from there, but not quickly enough to prevent another murder. The Baron, his daughter, and the daughter’s boyfriend picked Taylor out of a photo lineup, and also identified Spensir Mourey as the younger robber, the one with the duct tape. Taylor meanwhile suffered two broken heels after jumping off a roof. Instead of slowing his crime spree, however, he merely shifted his game-plan from using a bike as a getaway vehicle to killing someone, anyone, in order to steal their car.

While police hustled for warrants and Ferguson cased an apartment frequented by Taylor, Taylor was inducing two young accomplices, a man and a woman, into faking a fight at a bar. Court and police records would later describe how the woman then pretended she needed a ride and lured a 22-year-old man back to Taylor’s place. There, Taylor pressured one of his young charges to kill the man. They dismembered and buried the body in a shallow grave outside the city of Eugene, next to an underground stash of guns and a burn pile of cast-off items.

Taylor was arrested six days later. While he was in custody, police searched his girlfriend’s apartment and found several items from the Baron’s home. Upon questioning, the girlfriend confirmed Taylor’s involvement in the recent murder, and once they had him in custody, Taylor confessed to both the murder and the home invasion to spare his girlfriend any charges. He told the police he learned about the von Bothmers from a young guy, an old boyfriend of Netta’s. According to court documents, Taylor thought the Baron was a liar and a thief—in his view, a worthy target for a robbery.

To the Baron, news of Taylor’s arrest should have been a huge relief; the man who had nearly killed him, Netta, and her boyfriend had been caught. It might have even felt vindicating: The Baron was appalled that police had entertained the possibility that he engineered the break-in, complete with violence and death-threats at gunpoint. To be accused (or to feel accused) of such a thing when in fact he was a victim was just galling.

But the Baron’s behavior throughout the ordeal, during Taylor’s trial, and even afterward, can only be characterized as still more bizarre. He had come face-to-face with a ruthless murderer and lived to tell about it. Yet instead of thanking God or expressing sympathy to the murder victim’s family, the Baron continued, and continues, to accuse Sikkens of setting up the whole thing. It’s as if what had happened, an attack in his home by a convicted murderer, just didn’t register, couldn’t register. His old business partner hadn’t hired a hitman? His home wasn’t full of priceless artwork? The coronation isn’t next week? Nonsense.

After the trial concluded, the Baron was already on to his next implausible story: Sikkens hadn’t acted alone. He had conspired with the “dirty cops” of the Lake Oswego Police Department to steal the Baron’s art and heirlooms. (Sikkens denies all this, of course.) A year after the case was closed, Ferguson’s colleagues began receiving records requests from the Baron’s lawyer, seeking information about items recovered from the crime scene but not yet returned: a silver brooch, some sort of skull, a colored bowl, a Fabergé egg. In the winter of 2016, the Baron filed a tort claim, too, arguing police never returned his stolen valuables. Not only that, but police were the ones who had stolen them in the first place, concealing the thefts under the guise of the robbery.

The city’s insurer brushed aside the Baron’s complaints; an appraiser had previously concluded the recovered heirlooms the Baron sought compensation for were nothing more than costume trinkets. Besides, the von Bothmers had already received an insurance settlement on the order of $110,000. So that’s when the Baron decided to go to the press.

When he first called a reporter, the Baron claimed that Taylor and his sidekick Mourey were just fall guys. Detective Ferguson and other Lake Oswego Police officers were the real villains. “[T]hey broke into my wife’s locked safe, which wasn’t part of the robbery, took somewhere around $45 and $60 million in rubies and sapphires and emeralds…” Paperwork filed by the Baron’s lawyer claims that this lost loot, now valued between $180 million and $250 million, included: an Annette v. Droste hair necklace, a Crown medal, a von Bothmer portrait painted on ivory on a pearl necklace, a stack of Revolutionary War-era bills, a Droste Hulsolf lapel pin, an Invicta watch, original manuscripts from the Grimm Brothers, cash, tiaras, jade statues, and two signed copies of Mein Kampf.

It was April 2016 and the reporter was me, Lee. The Baron found my name after reading articles I had written in 2009 that were unrelated to his life but had been critical of the Lake Oswego Police. He invited me over for tea, hoping for a sympathetic ear and, I presume, a megaphone for broadcasting his dispute, leverage for a settlement, perhaps.

“They’re still harassing me,” he said, referring to the police. “They follow us, they point laser lights through our windows, they—recently a state trooper called my attorney and said, ‘Well, you know you need to let us know what’s going on.’ These bizarre incidents. And, of course, the death threats.”

Before taking a seat in his crowded living room, the Baron gave a brief tour, pointing out replica artwork, shrunken monkey skulls, and the makeshift chapel in a corner of the reading room. When it was finally time for an interview, the Baron and Baroness brought out a large binder full of newspaper clippings, printed-out emails, and other documents; proof.

But when asked to answer basic questions—an appraisal of his riches, for instance, or about apparent inconsistencies in his account—the Baron grew increasingly agitated. Soon his voice became louder, his face reddening with fury over everything that he and his family had suffered at the hands of the Lake Oswego Police and their accomplice, Bill Sikkens. When he finally couldn’t take it anymore, the Baron stomped out of the room, hollering about a sickening conspiracy. Halfway up the staircase, he stopped on the landing for one last burst of shouting, his hands rattling the banister until it looked like it might break and send the Baron tumbling. It didn’t, though, and a moment later he disappeared. Interview over.

This story was produced in partnership with Delve and Six Foot Press.